After the previous volume’s sojourn through the Iberian Peninsula, the fourth installment of Severin’s Danza Macabra returns the series to Italy with a uniformly entertaining quartet of titles that resolutely tick off the boxes in the Gothic Cinema We Love checklist: cobweb-laden crypts, medieval castles and other ruins, inky black shadows (captured in both moody monochrome and creepy color), and tales of revenge from beyond the grave. What’s more, this set also offers fascinating takes on some of horror’s most iconic figures.

An underrated vehicle for scream queen Barbara Steele, Massimo Pupillo’s Terror-Creatures from the Grave, from 1965, is a slow-burn gothic chamber piece that rachets up the tension bit by bit, until the filmmakers let all hell break loose in the last 15 minutes. Even then, it’s fascinating to note exactly how much the film achieves with so little.

Apart from some chillingly goopy makeup, the effects on display in Terror-Creatures from the Grave consist of little more than jittery POV camera movements and some cannily thrown shadows. This is definitely horror filmmaking in the Val Lewton vein, well served by the slinky camera moves and the ravishingly tenebrous monochrome imagery.

Written by Roberto Natale and Romano Migliorini, the film is set in the year 1911. This allows for a tinge of modernity, in the form of telephones and crank-started automobiles, to color the otherwise pre-industrial proceedings. As with many a gothic tale, the narrative involves the dead hand of the past coming back to exact grisly revenge upon the present. Here that’s represented by the restless spirits of plague spreaders buried on the property of a medieval villa owned by Professor Jeronimus Hauff, who’s been dead almost exactly a year at the start of the film.

Through mediumistic pursuits that got him booted from the university, Hauff managed to contact and harness the villa’s ghostly population into seeking revenge for his murder, threatening along the way Hauff’s widow Cleo (Steele), daughter Corinne (Mirella Miravidi), and helpful attorney Kovac (Walter Brandi). In a bravura move, Pupillo stages the inevitable flashback to Hauff’s demise not as remembered by any of the participants, but by putting it on display in a cursed mirror, another trope often deployed in gothic literature and film. Terror-Creatures from the Grave is also unusual in that it culminates in ritualistic purification by water, rather than the more typical cathartic inferno that concludes many other tales of this sort.

From 1971, Filippo Walter Ratti’s The Night of the Damned ramps up the eroticism that was rather teasingly employed in Pupillo’s film, with its fleeting glimpses of people’s bare backs and sides, instead tipping over into envelope-pushing softcore at times. Like Terror-Creatures from the Grave, Ratti’s film could have been set hundreds of years ago, save for several flashes of the modern day, which, given that they’re mostly taken up with ongoing murder investigations, could align the film with the giallo craze that was just then kicking into overdrive.

As the film owes a clear debt to “The Fall of the House of Usher,” it comes as little surprise that early on it name-drops Charles Baudelaire, who was an early advocate and translator of Edgar Allan Poe. Screenwriter Aldo Marcovecchio cleverly works the nod into a plot point involving a hidden code, something that wouldn’t have been out of place in a Poe story like “The Gold Bug.” The relevant quotes also signal Baudelaire’s interest in the ineluctable link between sex and death, a perverse and decadent connection the film pursues in its own inimitable way.

Renowned journalist Jean Duprey (Pierre Brice), along with his wife, Danielle (Patrizia Viotti), is summoned to the remote and allegedly haunted mansion of his childhood friend Prince Guillaume de Saint Lambert (Mario Carra). Ushered into the house by Guillaume’s wife, Rita (Angela De Leo), they’re informed that Guillaume is suffering from a sort of hereditary disease that gives him fits and sends him into spells of frenzied violin playing. Eventually, it turns out that all this has to do with a witch burned at the stake by one of Guillaume’s ancestors back in the 17th century, though this development more readily suggests the works of Poe’s confrere Nathaniel Hawthorne, particularly The House of the Seven Gables.

Ratti’s film invokes a time-honored gothic trope by depicting two women with very different dispositions: dark-haired femme fatale Rita and blond naif Danielle. What’s more, the film follows other works of Italian gothic cinema like Mario Bava’s Black Sunday that conflate the figures of the witch and the vampire. Though Guillaume is Rita’s first victim, we never see any overt acts of predation against him, whereas, when she turns her attention to Danielle, we’re treated to protracted sex scenes that further involve several sapphic sex slaves.

These softcore scenes tend to bog down the film’s pacing, especially in the final act, when it should be tightening up. The finale also resolves itself quite abruptly, almost as though parts of it weren’t filmed owing to budget constraints. But the story is clever and well executed. The film is loaded with gothic ambiance, exquisitely shot in lurid color by cinematographer Girolamo La Rosa, and boasts a terrifically atmospheric score from composer Carlo Savina.

Luigi Batzella’s The Devil’s Wedding Night, from 1973, goes whole hog with the allusiveness glimpsed in The Night of the Damned, folding in knowing references to Poe’s poetry, Wagner’s operas, and the demon Pazuzu from William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel The Exorcist (a year before the film version). The narrative brings together the two most iconic vampires in film history: Count Dracula and Countess Bathory. And, as if all this weren’t enough, Batzella’s film lifts a couple of key plot points from Roman Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers.

It’s all done in a light and playful manner, though this doesn’t mean that The Devil’s Wedding Night stints on the chilling or even positively psychotronic moments. Witness a round of Dionysian wine quaffing that suddenly morphs into a bizarre psychedelic montage straight out of the finale of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. And much of the film’s more surreal and oneiric imagery wouldn’t be out of place in a Jean Rollin film.

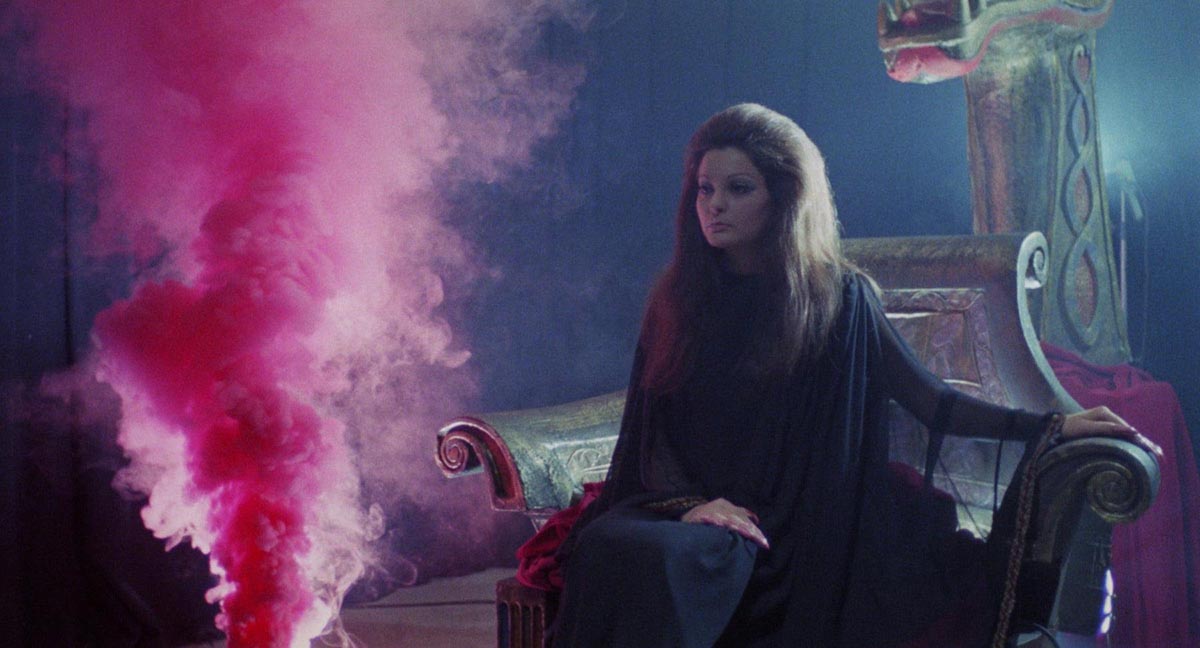

Mark Damon (the male lead of Roger Corman’s House of Usher) does double duty playing Karl and Franz Schiller, twins of noticeably divergent dispositions: one sober and studious, the other an opportunistic wastrel. Genre icon Rosalba Neri (the female lead of Lady Frankenstein, which was included on the first volume of Danza Macabra) plays Countess Dolingen de Vries. In another of the film’s literate games, her name is a riff on the Bram Stoker story Dracula’s Guest. By the film’s blood-soaked climax, it becomes clear that she is in fact Dracula’s widow, out to reincarnate him using a Satanic ritual and Karl’s body as the host.

The Devil’s Wedding Night contains less flesh than The Night of the Damned, but we’re treated to the indelible image of the resplendent Rosalba Neri slowly rising from a fog-shrouded tomb covered only by the blood of the latest virgin sacrificed to her eternal youth and beauty. The film also reflects trends in the softcore cinema of the era with its lengthy depiction of a tryst between Damon and Neri, the latter showing off quite a lot more of her assets than her male co-star.

In keeping with the changing tenor of the times in post-Night of the Living Dead horror cinema, the filmmakers give their gothic tale a downbeat ending. Unlike Terror-Creatures from the Grave and The Night of the Damned, which conclude with the restoration of the status quo as embodied in a pair of romantic lovers, The Devil’s Wedding Night closes on an ironic and ambiguous note that portends the spread of its hitherto contained vampiric plague.

Also released in 1973, Baba Yaga is an adaptation of Guido Crepax’s erotic comic by writer-director Corrado Farina, whose They Have Changed Faces can be found in the second volume of Danza Macabra. The story begins when Milanese fashion photographer Valentina Rosselli (Isabelle De Funès) runs into an older woman who refers to herself as Baba Yaga (Carroll Baker), a name that alludes to a figure out of Slavic folklore. Baker’s glamorous, gauzy Norma Desmond-inflected portrayal of the character doesn’t exactly gibe with what we expect of a cannibalistic crone who swoops around the forest in an oversized mortar wielding a giant pestle.

Because Valentina is a shutterbug by profession, and her lover, Arno (George Eastman), a commercial director, the film is besotted with images. Right off the bat, Farina invokes Crepax’s sinuous pen-and-ink artwork for the opening title cards, and later sequences in the film even replicate the arrangement of panels in Crepax’s fumetti (or comic strips) by using black-and-white still photos, especially for a love scene that rigorously fragments the lovers’ constituent anatomies. Carrying through on this motif, Baba Yaga ends up apparently cursing Valentina’s favorite camera, so that some mishap befalls anyone she shoots.

Despite its folkloric connection, Baba Yaga is the least overtly gothic film in this Danza Macabra set. Baba Yaga’s “lair” is no ruined castle, let alone a hut propped up on spindly chicken legs; it’s nothing more than a rundown villa stuffed with early-20th-century appurtenances like gramophones and manual typewriters. The most uncanny among these decorations is a russet-haired doll all gussied up in leather dominatrix gear that Baba Yaga calls Annette and summarily bequeaths to Valentina. When the doll magically comes alive late in the film, she’s played by Ely Galleani, a veteran of Italian genre cinema.

Annette ties the film into another preoccupation that runs throughout Crepax’s body of work: sadomasochistic eroticism. This fixation is signaled early on when Valentina pages through a volume of Marquis de Sade’s Crimes of Love. Though there’s only one rather restrained scene of bondage and discipline, it’s enough to align Baba Yaga with other European erotica like The Libertine, The Punishment, or any of the films of Alain Robbe-Grillet from the period.

Severin has given all four films in the set impeccable 4K restorations and, for the first time in the series, makes them available on UHD discs as well as standard Blu-rays. Each title is accompanied by a satisfying range of extras, including cast and crew interviews, visual essays, and commentary tracks, even a CD of soundtrack cues from composer Piero Umiliani. The set provides another bounteous helping of spectral pleasures for the gothically inclined viewer, proving once again that the bottom of this particular barrel is absolutely nowhere in sight.

Danza Macabra Volume Four: The Italian Gothic Collection is now available.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.