A lively, chaotic swirl of contradictions, Jaws is a thriller that played a role in the entire restructuring of Hollywood’s methods of selling its films to the public. It was the sure-to-be calamity that became one of the most beloved and quoted films of all time—a certain generation’s Citizen Kane that gave rise to a legendary, controversial filmmaker and seemingly turned everyone else into aspiring directors. It also played a role in the rise of an obsession with a kind of theme-park movie that gluts global cinemas to this day. That’s a lot of baggage for any film, much less a monster movie with grade-Z roots, to live up or down to.

The surprise is how good it was and still is. The film is a strange mixture of the ultra-controlled and the wild and wooly. Imagine if portions of Psycho were spliced into one of Hal Ashby’s early films and you’d be closer to the film’s tone than you might think.

Jaws is neatly split into two almost entirely different films: The first half is a sophisticated comedy in which violence and despair are allowed to make occasionally discombobulating intrusions, and the second, daringly, is an even more violent parody of the self-flattering macho courtliness that we often find in existential, chest-thrumming stories of all kinds. The Peter Benchley novel that inspired the film played its material dead-straight, and it’s a grim, dull endeavor that got by on the enormous primal appeal of its high concept, but the filmmakers took the basic structure, threw out most of the busy plotting, and created a black parody of greed, studliness, and self-entitlement—in other words, a parody of America.

The director, of course, is Steven Spielberg, and Jaws represented a major turning point in his career, and not just for the obviously lucrative reasons. The film was the capper of a kind of thematic trilogy that introduced Spielberg to the world. First there was Duel, a nihilistic film that follows an innocent man as he’s relentlessly pursued by a seemingly prehistoric tractor trailer. Then, The Sugarland Express, a warmer, even more disturbing action comedy that follows a woman’s desperate efforts to kidnap her own child. And then Jaws, which fuses the sensibilities of the first two to create, whether it’s intentional or not, a disconcerting portrait of America trying to stake its claim in a willful naïveté in the wake of all of the sobering events that define the country in the late 1960s to early 1970s: Watergate, Kent State, Vietnam, etc.

Spielberg would eventually indulge that naïveté without irony (if not nearly as often as he’s accused of), but his first few films are the work of a ferocious talent who was pretty much trying anything for effect. The near-miracle of Jaws, which involved the work of a few uncredited screenwriters, as well as impromptu story sessions and ad libs, lies in how harmonious it is. The dissonances feel preordained, and are also the source of the film’s lasting power.

Spielberg would grow self-conscious as he became more famous, trying for (and often achieving) mythical, iconic effects, but the young Spielberg was adept at capturing the quotidian that defines the working class. The people in Jaws appear to actually work for a living: The offices are worn and shabby, the homes are messy and constantly marked by the demands of raising children, and the adults trade in the sort of world-weary in-jokes that should be familiar to anyone who works a thankless job in an effort to barely pay the bills each year.

For that attention to detail, and for the sly storytelling (all of the film’s major set pieces are foreshadowed in fashions so subtle you’ll miss them the first time), Jaws is the rare monster movie that doesn’t idly mark time as we wait for the next big shock. And the details only amplify those shocks; people tend to forget how ruthless a director Spielberg once was.

By 26, he was already an impressive formalist, and he fills his wide shots with details and visual curlicues that maintain a continual apprehension. The film, as Pauline Kael wrote, has tricky editing rhythms that never properly prepare you for the scares. (Though people often misremember the first time we see the shark; it’s not the scene where Brody is shoveling chum, but briefly, and terrifyingly, during the moment before a fisherman loses his leg.)

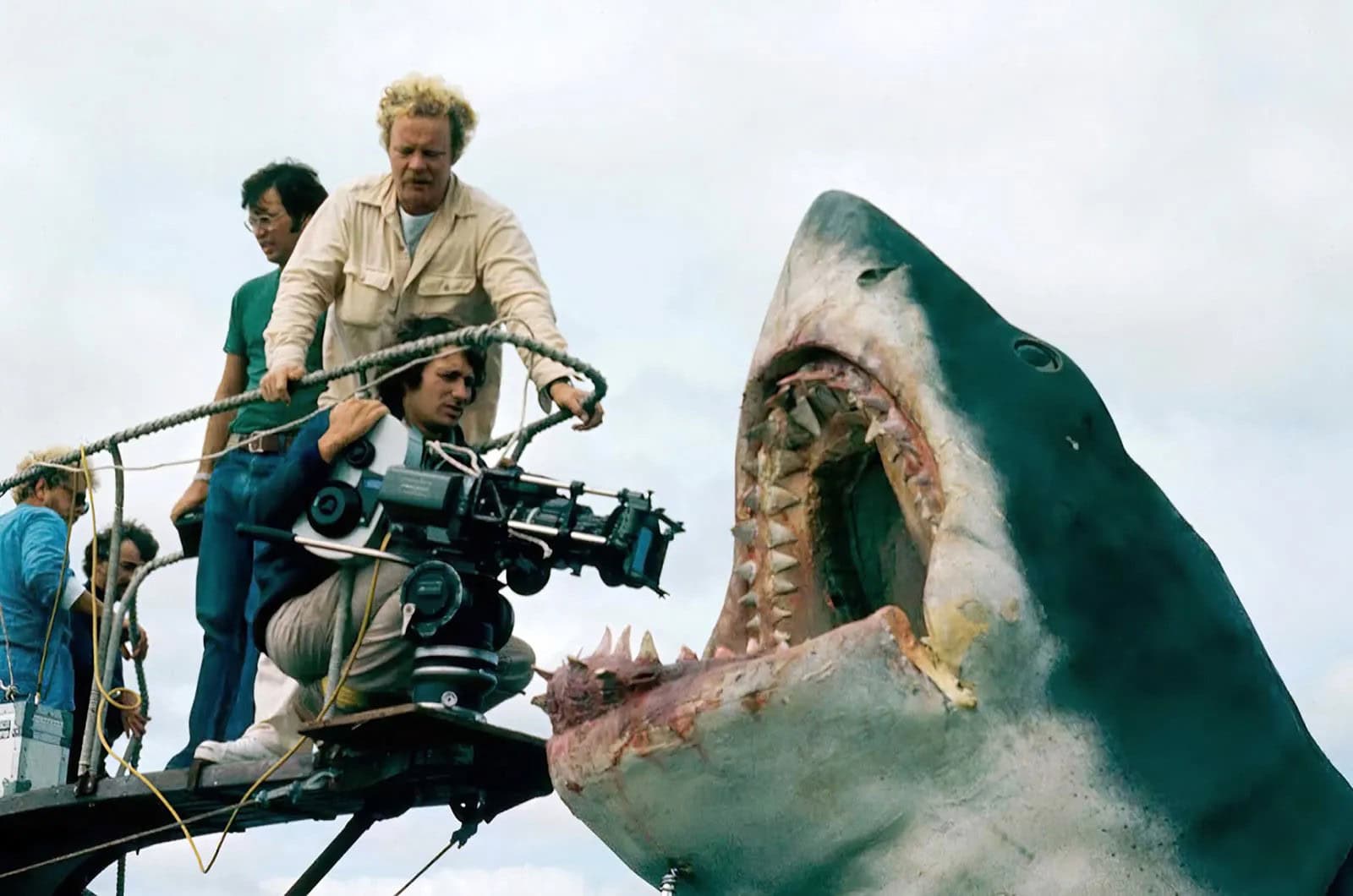

And, yes, the shark, that unyielding colossus, looks rather fake when we finally get a good look at him, which works entirely in the film’s favor. The shark, effectively built up as an object of myth and obsession for the first half of the film, would be a crushing disappointment if it looked “real,” something most contemporary monster movies, in their reliance on generic CG, seem to sadly fail to comprehend. The shark in Jaws is the shark of our collective worst nightmares, almost otherworldly in its enormity (it sometimes appears to be as big as the truck in Duel) and texture. It’s also a great big phallic joke, the agent of the blowhard Quint’s (Robert Shaw) destruction. The shark can mean anything you want it to mean, or nothing, and that uncertainty epitomizes this movie’s lasting appeal. Jaws is the pop masterpiece as happy accident—a parody of America’s can-do spirit that’s also, by the end, a celebration of it.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.