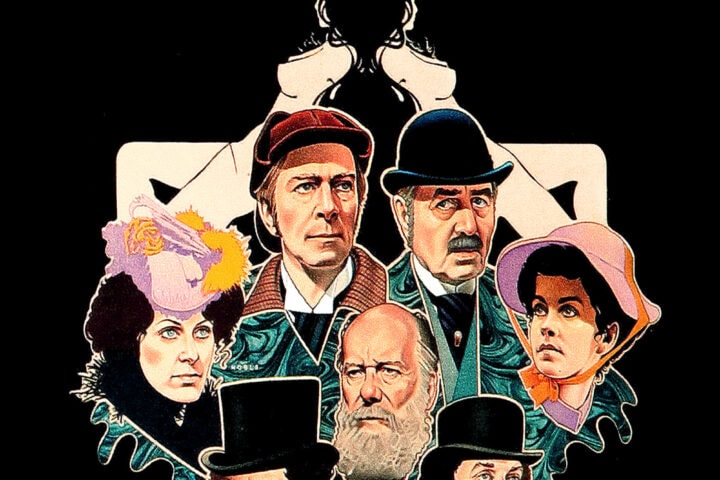

![]() Arthur Penn’s Night Moves is one of the great revisionist noirs, taking its place alongside Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye and Roman Polanski’s Chinatown. Like those films, it not only brazenly subverts the tropes of the classic Hollywood private eye film, but also uses the genre’s pervasive aura of moral corruption and social anomie to comment on the American scene in the wake of political scandals and the collapse of the 1960s counterculture into the rampant self-absorption of the Me Decade. All three films eschew pat resolutions, let alone the comforts of a return to status quo order.

Arthur Penn’s Night Moves is one of the great revisionist noirs, taking its place alongside Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye and Roman Polanski’s Chinatown. Like those films, it not only brazenly subverts the tropes of the classic Hollywood private eye film, but also uses the genre’s pervasive aura of moral corruption and social anomie to comment on the American scene in the wake of political scandals and the collapse of the 1960s counterculture into the rampant self-absorption of the Me Decade. All three films eschew pat resolutions, let alone the comforts of a return to status quo order.

Night Moves cadges elements from classic noir films. It lifts basic plot points about the search for the runaway daughter of a moneyed family from Howard Hawks’s The Big Sleep, and emulates that film’s excessively labyrinthine narrative, though here you probably don’t need to pay anybody to explain what’s going on in the end. The film’s bravura finale also combines aspects of Hawks’s To Have and Have Not (maritime smuggling operations) and John Huston’s Key Largo (climactic gun battle on a boat).

Former football player turned detective Harry Moseby (Gene Hackman) is on the hunt for Delly Grastner (Melanie Griffith), the daughter of former actress (Janet Ward) who’s run away into the demimonde of stuntmen and location film shoots. But the man is distracted from the case by the discovery that his wife, Ellen (Susan Clark), has been having an affair with posh Malibu playboy Marty Heller (Harris Yulin). In this way, Night Moves delves further into the fallible personal life of its resident private dick than Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett ever did.

Harry’s existential crisis is perfectly summed up by a pointed exchange with Ellen. Returning home from a rendezvous with Marty, Ellen finds Harry watching a football game on TV. “Who’s winning?” she asks. “Nobody,” Harry informs her. “One side’s just losing slower than the other.” Harry, who already knows about Marty, has the sense that he can’t compete on a socioeconomic level. His business is a bust, but he clings to the work out of a sense of dogged obligation.

Harry’s sense of personal failure carries through to the case. In the end, as he admits to Paula (Jennifer Warren), who passes for the film’s femme fatale, he didn’t solve the case. It just sort of fell on top of him. Harry’s incapacity stems from precisely the same inability to see what’s right in front him as the chess master whose loss of a match Harry demonstrated to Paula earlier. That same loss, which involves “three knight moves,” also loosely provides the film its title, along with the idea that much that happens in the film happens under cover of the dark.

Night Moves couches its critique of social upheaval in seemingly minor details. At one point, Paula asks Harry where he was when Kennedy was shot. He wants to know which one. Paula claims it’s the one question everyone can answer. However deep we may be in own personal quagmires, we can still easily measure our lives by national catastrophes. The theme continues when Harry goes to view footage of the accident that killed Delly, which is presented like the Zapruder film of J.F.K.’s assassination. But, since it involves the death of an innocent in a car crash, also brings to mind Teddy Kennedy and Chappaquiddick.

Throughout Night Moves, Penn foregrounds the act of looking. There are frequent shots of characters regarding each other through window panes or screens. Large fisheye lenses adorn windows in both Harry’s house and Marty’s seaside bungalow (courtesy, one senses, of Ellen’s decorative savvy). The “freak” mechanic Quentin (James Woods) first glimpses Harry through the visor slit of his welding mask. Most hauntingly, Harry watches in stricken helplessness through a boat’s glass bottom as his erstwhile friend Joey Ziegler (Edward Binns) slowly drowns. Ironically, the boat is named Point of View.

The endings of both The Long Goodbye and Night Moves hinge on the private eye’s betrayal by a supposed friend. But in the former, Marlowe’s revenge is played with a shit-eating grin to the ironic strains of “Hooray for Hollywood.” Night Moves, on the other hand, is far more despairing. The abiding sense is that of pointlessness. The haunting final image is a boat endlessly circling bits of wreckage, as perfect a metaphor for futility as you could ask for.

Image/Sound

Criterion’s 2160p UHD presentation of Night Moves looks spectacular. The film’s color palette comes across as rich and vibrant, with some evocative use of primary hued lighting. The HDR transfer admirably conveys DP Bruce Surtees’s assured use of the dazzling Florida sunlight as well as shadowy night-for-night location shooting. Audio comes in a LPCM mono mix that sounds strong and clear, doing right by Michael Small’s excellent score, which alternates between menacing strings and infectious samba-inflected rhythms.

Extras

Matthew Asprey Gear, author of Moseby Confidential: “Night Moves” and the Rise of Neo-Noir, provides a deeply researched and engaging commentary track that focuses on the creative tug of war between director Arthur Penn and screenwriter Alan Sharp when it came to shaping the film’s final shape and tone. In a fascinating bit of cross-referencing, Gear draws not only from Sharp’s original shooting script, but also the novelization that Sharp wrote for the film.

Also included here are two interviews with Penn. The first, from a 1975 episode of Cinema Showcase, has him talking at length about the film, his career, and especially the cult fandom for 1965’s Mickey One. The second and much shorter one consists of excerpts from a 1995 career retrospective doc, in which the filmmaker opines about his visual strategies for Night Moves.

In an audio-only interview, actress Jennfier Warren talks about swapping roles in the film, working with Penn and Gene Hackman, the scuba dive scene, and the studio’s misguided attempt to sell Night Moves as an action movie. Also included is a brief making-of doc produced during the location shoot on Sanibel Island. Lastly, the booklet insert includes an essay by critic Mark Harris that situates the film in the context of the New Hollywood movement.

Overall

Bleak and despairing, Arthur Penn’s revisionist film noir classic Night Moves gets an impressive sprucing up and some very satisfying extras.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.