Severin follows up their 2023 collection of Italian gothic titles with an essential second volume that brings together three films and a miniseries. Each work takes a very different approach to the gothic as both a visual aesthetic and a set of thematic preoccupations. The results range from virtually archetypal to resolutely revisionist. For this well-appointed set, Severin provides a veritable bounty of bonus materials: new restorations, alternate cuts, commentary tracks, cast and crew interviews, visual essays, even a soundtrack CD.

Antonio Margheriti’s Danza Macabra, from 1964, is one of the very best Italian gothic films. It simply oozes with atmosphere courtesy of Riccardo Pallottini’s moody monochrome cinematography, and, while the violence remains relatively restrained, Margheriti brazenly pushes the envelope when it comes to nudity and some suggestive sexual content. Likely as a bid to cash in on Roger Corman’s Poe Cycle, Danza Macabra not only claims to be based on a Poe story but even features the author as a character. The film cannily builds to a grimly ironic and downbeat ending that paradoxically manages to offer a glimmer of otherworldly hope.

Better known as Castle of Blood, Danza Macabra opens with journalist Alan Foster (Georges Rivière) meeting Poe (Silvano Tranquillo) at a tavern for an interview. Poe is in the middle of regaling tablemate Lord Thomas Blackwood (Umberto Raho) with the grisly finale of his story “Berenice.” It’s gratifying to note that, between these details and a later conversation where Poe relates his famous dictum about the death of a beautiful woman being the most poetic subject matter, screenwriters Giovanni Grimaldi and Bruno Corbucci reveal some familiarity with Poe’s works. Their genre literacy is further confirmed by the fact that Lord Thomas’s surname is almost certainly taken from Algernon Blackwood, a British purveyor of the weird tale.

Foster rashly accepts Blackwood’s wager to spend the night in the lord’s castle on All Soul’s Eve, which Blackwood claims no one has ever managed to do before. Once Poe and Blackwood drop Foster off at the castle gates, the film effectively ratchets up the eerie atmosphere. The camera spends almost 15 nearly wordless minutes following Foster around the grounds (including, of course, the family burial ground) and through the castle. In the end, he encounters raven-tressed Elisabeth Blackwood (Barbara Steele), with whom he’s instantly smitten.

But any attempt at romance proves ill-fated, given not only the presence of disapproving family friend Julia (Margarete Robsahm), but even more definitively by Elisbeth’s sudden murder at the hands of resentful stable hand Herbert (Giovanni Cianfriglia). When everyone apparently disappears in a single stroke, “metaphysical medicine” man Dr. Carmus (Arturo Dominici) turns up to explain things: Anybody who dies in the castle is doomed to return once a year to relive the events of their demise, all of which Foster now witnesses.

The erotic element in the ensuing emotional betrayals is fairly graphic. When Herbert drags Elisabeth into the stable, it’s clearly implied that he pleasures her orally. And it turns out that Julia’s interest in Elisabeth isn’t entirely friendly when she quite literally presses herself on her after a daisy chain of murders leaves them the only would-be lovers left alive. The most explicit moment transpires when newlywed Elsi (Sylvia Sorrente) sheds her bridal gown while her husband is off getting himself dispatched by vengeful ghosts.

Probably best known in the States as the male lead in Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad, Giorgio Albertazzi writes, directs, and stars in 1969’s Jekyll, a compelling four-part TV adaptation of the Robert Louis Stevenson classic Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Eschewing the Victorian trappings of many previous versions, Albertazzi chooses to bring the material up to date, making Jekyll a molecular biologist whose transformation into his alter ego, Edward Hyde, is a matter of evolutionary mutation. This allows him to indulge in a lot of high-minded philosophizing about the humanistic responsibilities of science in the age of the atom bomb and genetic modification. At the same time, Albertazzi preserves much of the source material’s moralistic ruminations on the battle between good and evil for the human heart.

Jekyll unfolds like a typically talky teleplay, peppered with protracted monologues and dialogues, akin to a Golden Age of television program like Playhouse 90. But Albertazzi finds ways to keep the visuals interesting, utilizing unusual shot compositions, sinuous camera movements, and some striking set designs. The look here is ultramodern: clean lines, abstract shapes, shiny metallic surfaces. The score is also cutting-edge, dissonant, and abrasive.

In keeping with its late-’60s origins, Jekyll maintains a fascinatingly double-edged attitude toward the youth culture. Jekyll raps at length with his students, tacitly approving of their “Fast for Peace” placards and affinity for the Berkeley student movement. So the altruistic attitudes of the counterculture seem to receive a measure of approbation. For his part, Hyde festoons his rented barge with Pop Art paintings and sculptures, even going so far as to try his own hand at it. Is this development meant to imply that art is somehow fundamentally evil? Is it, like Hyde himself, the result of an unlawful act of creation? Albertazzi leaves it for the viewer to decide.

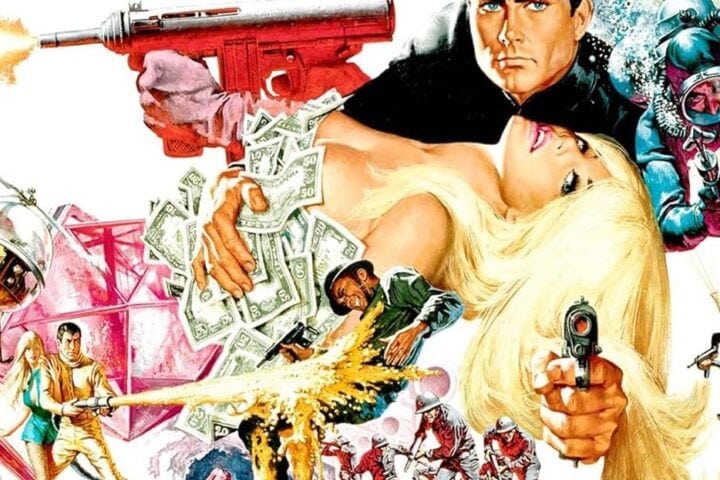

Corrado Farina’s They Have Changed Their Face, from 1971, is almost certainly the only movie to end with a quote from social critic Herbert Marcuse. Then again, it’s also one of the few films that brazenly posits its bloodsuckers as being synonymous with the capitalist system. The film begins when automobile manufacturer Giovanni Nosferatu (Adolfo Celi channeling his role as industrialist villain Emilio Largo in Thunderball) summons middle-management type Roberto Valle (Giuliano Esperanti) to his mountaintop villa for a working weekend.

Along the way, Roberto picks up hippie, Laura (Francesca Modigliani), whose freewheeling lifestyle is signaled by her unwillingness to lead a settled life, not to mention the fact that she’s completely bare-breasted under her shaggy overcoat. Roberto makes her wait in the car while he goes in to scope out the terrain. He’s received by Nosferatu’s fetching aide-de-camp Corinna (Geraldine Hooper), who plays increasingly seductive nursemaid to the naïve Roberto when he’s not getting face time with Nosferatu. It turns out that the mogul’s plan is to promote Roberto to president of his car company, a fate, he intimates, that has been planned for him since birth.

Farina pays cheekily parodic homage to various aspects of vampire lore. For one thing, Roberto’s superiors are named Stoker and Van Helsing. The grounds of Nosferatu’s redoubt are guarded not by packs of ravening wolves but by vrooming little Fiats in the habit of running over both interlopers and those who have fallen out of favor with Nosferatu. Farina contrarily eschews other aspects of generic lore: There are no fangs on display, no aversion to crosses, no avoidance of sunlight. Aside from the eerily fog-shrouded local village, the only other real concession to gothic mood is a quick trip Roberto makes into the Nosferatu family crypt.

The film’s central set piece occurs when Roberto oversees a meeting between Nosferatu and a cabal of power brokers that includes doctors, lawyers, advertising execs, and a bishop. The still all too relevant point Farina wants to make is that every aspect of Italian (and not only Italian) society colludes to control the populace through their consumerist desires. Even the counterculture has already been recuperated into the system, as seen in fake ads for birth control pills and an aerosol can that sprays LSD. The funniest part of the scene, though, involves a couple of spot-on parodies of art house idols Godard and Fellini, one of which involves a lengthy recitation from Marx, the other a sad clown playing the tuba. A final faux ad encompasses the Marquis de Sade and some exceedingly cruel foot tickling.

In a last-ditch escape attempt, Roberto returns to his car only to find Laura all gussied up like a bourgie matron, about to set off into a future now destined to include marriage, pregnancy, and housewifery. The film concludes on a freeze-frame of the acquiescent handshake between Roberto and Nosferatu. Farina’s final, despairing punch line suggests that there’s no exit from the system. All that’s left are these final words (possibly) from H. Marcuse: “Terror, today, is called technology.” And you thought all you were getting was a nice, safe vampire movie!

Definitely the runt of the litter, Paolo Lombardo’s The Devil’s Lover, from 1972, is plagued by a number of factors. The nearly nonexistent plot has a penchant for introducing characters at seeming random, and their sole purpose is to perform one oft-bizarre bit of business before exiting the film. Aside from some evocative castle exteriors, the production values are downright risible. And the editing at times approaches the incoherent. What the film does possess is the inimitable presence of genre icon Rosalba Neri, who completely dominates the proceedings, eclipsing top-billed Edmund Purdom with the sheer force of nature of her performance. It also has some modestly intriguing things to say about the changing role of liberated women.

Accompanied by two friends whose names we never learn, Helga (Neri) arrives on the doorstep of a centuries-old castle that’s reputedly owned by the Devil himself, a proposition that the skeptical Helga openly ridicules at dinner when she notices a place has been set for an unseen guest. Later that night, she discovers a portrait that bears an uncannily resemblance to herself, depicting a woman in agony (or is it ecstasy?) while being burned at the stake. Taken with the vapors, Helga promptly swoons to the ground, only to awaken back in the 1500s, where she’s a village lass engaged to local lothario Hans (Nando Poggi).

An extremely melodramatic, and very hastily sketched in, love quadrangle soon develops between the betrothed couple, Helga’s friend Magda (Maria Teresa Pietrangeli), who’s in love with Hans, and roguish Helmut (Robert Woods), who’s in love with Magda. Seduction, blackmail, and a murder plot are the order of the day. We’re also treated to one unmotivated swordfight, a writhing satanic orgy complete with naked female vampire, and some decidedly Pied Piper-like flute-playing. A magically appearing and disappearing figure in a crimson hood turns out to be a chap named Gunther (Purdom), who just might be Old Scratch in the flesh.

Gunther offers Helga social and sexual liberation if only she will give herself over to him body and soul—an indecent proposal that she readily accepts. Her newfound freedom allows her to transgress all social bonds, forsake her parents, betray her new husband, even commit torture and murder. But the price for this independence proves to be the fate, the film suggests, that awaited any woman who forgot her place in the social system of the 16th century. When Helga awakens back in the present day, she’s free to leave the premises and pursue her own agenda as a liberated young woman of the early 1970s. Threadbare as The Devil’s Lover might otherwise be, it does reveal some fairly progressive sexual politics.

Danza Macabra Vol. Two: The Italian Gothic Collection is now available from Severin Films.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

Jekyll was an interesting take but too long with drawn-out scenes that added nothing but time to the production. It could have easily been under two hours. The minimal make-up, mainly the contact lenses, was very effective.