In one way or another, the shows on this list were high-risk endeavors that gloriously paid off.

The few mistakes occurring amid the gravity-defying craziness only served to illustrate just how beautifully close to disaster these performances always are.

Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson is historical revisionism for the late-term SNL era.

If you’re ready to have a gay old time, the funny flurries are showering New York these days.

Strangers in a Strange Land: A Cool Dip in the Barren Saharan Crick and In the Heat of the Night

A Cool Dip in the Barren Saharan Crick feels woefully under-rehearsed when not just plain amateurish.

Two Gentlemen of Lebowski frustratingly smirks at the concept of removing the Coens’ film from its context.

There’s a lot going on in its 75 minutes, and it’s great to see someone truly using the vast entirety of the wonderful Ellen Stewart Theater at La MaMa.

The enchanting spell of New York City shall likely draw Oklahomans, in all number of ways, for years to come.

Dylan Baker, always a reliable assist in stage and film, does work that is nothing short of transformative.

Suzan-Lori Parks’s blackly comic Southern gothic is sprinkled with poetic assertions on postwar distress and home-life abuses.

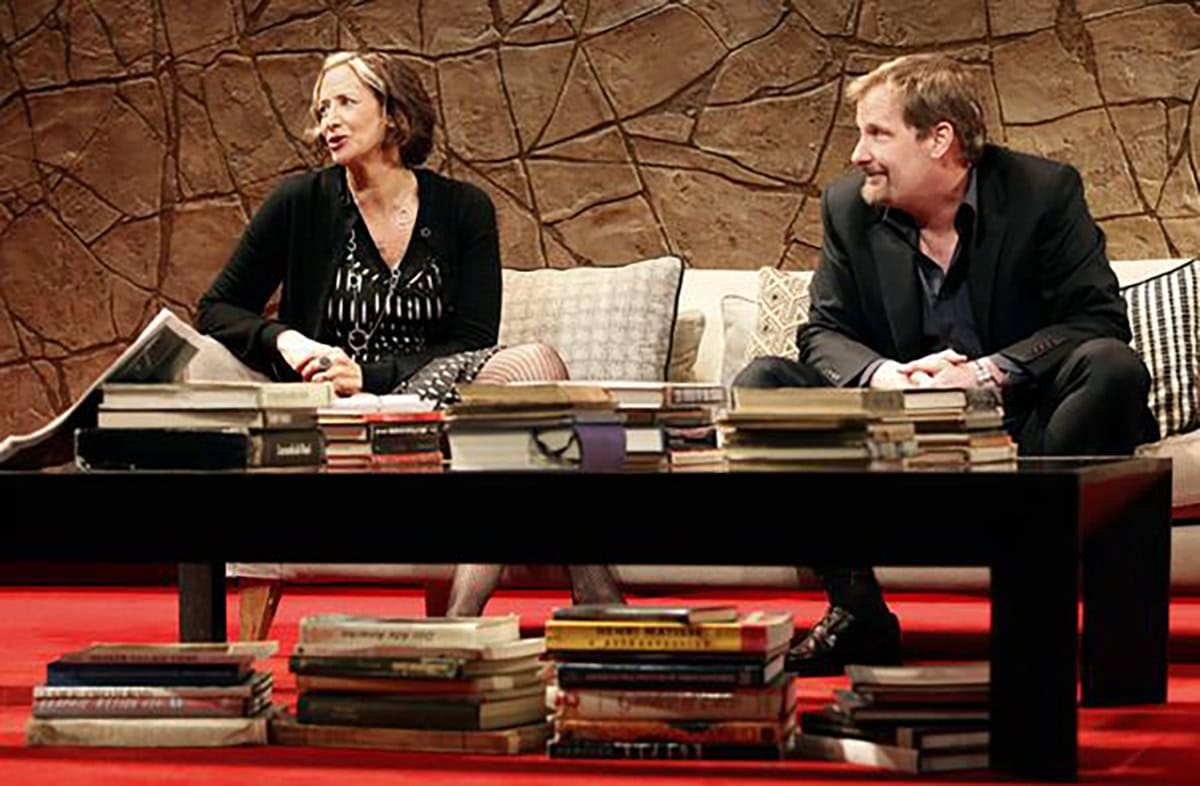

Next Fall isn’t about “old” times per se, but its content seems firmly rooted in the seriocomic patterns of seasoned old pros.

Despite its historical nature, The Temperamentals is anything but a dry history lesson.

Sure, Martin McDonagh is still pushing the envelope—but to where?

It’s awfully hard not to feel like you’re missing something throughout this Miracle Worker.

Here is a tragedy told with absolutely no momentum.

A gay renaissance appears to be hitting NYC theater these days.

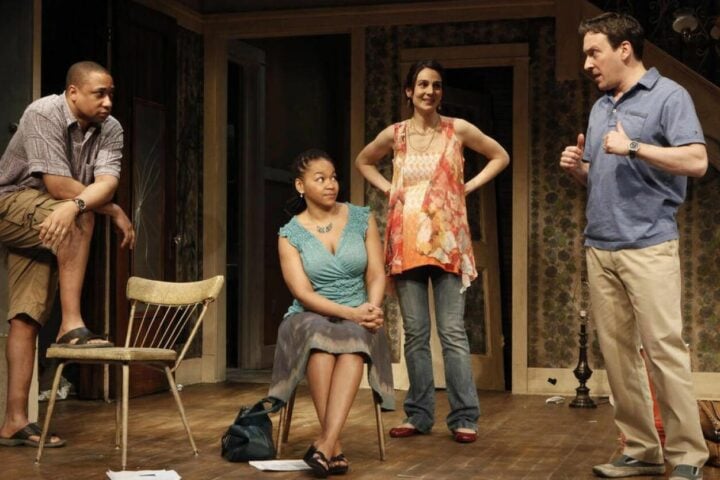

The strength of Clybourne Park lies in how Bruce Norris keeps subverting the types represented.

In the age of CGI and Cirque du Soleil, even the play’s technical “spectacle” often seems as retro as its fossilized script.

If Psych ever goes the way of this play’s title, he’s got a home on the stage whenever he wants it.

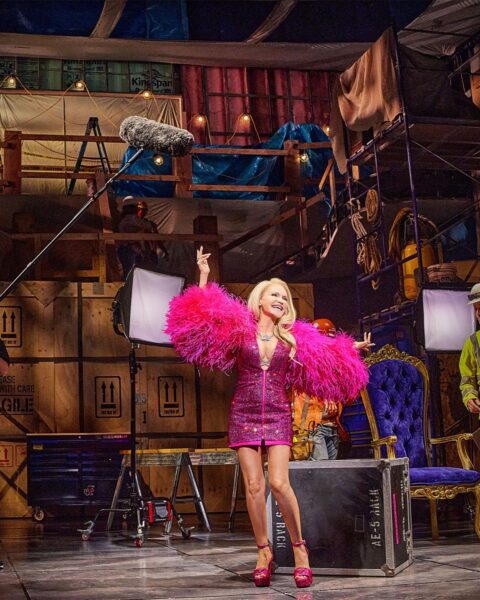

The play’s spectacle is so overwhelming that you nearly overlook its flaws.

The thumbprint of Alan Ayckbourn seems firmly impressed into the pages of playwright Lucinda Coxon’s Happy Now?