As we re-enter the circuit of in-person film festivals, the peculiarities of the physical world feel just as alluring as the movies themselves. Even the nuisances, or accidents, that emerge from the coils of a system battered by pandemic provisions are blunted by the excitement of acquainting oneself with tangible collectivity as if for the first time.

About half an hour south of Frankfurt, Mannheim is, in that sense, the perfect location for underscoring the pains and pleasures that the solidity of life has to offer. There’s something strangely anachronistic about this German city, which seems molded by heavy concrete, and more reliant on objects than screens in order to make its capitalist demands.

The area around the IFFMH’s main venues—the Stadthaus, the Atlantis, and the Cineplex Planken—is marked by the haptic grittiness, if not garishness, of 1970 aesthetics. There’s something decidedly analog about Mannheim, then, as a sight so decidedly pre-pandemic and pre-digital that one could almost forget that the 21st century has already swallowed us whole. There are bridal shops everywhere, enormous cupcake dresses in their display windows.

Elsewhere, stores teem with unabashedly bulky Birkenstocks, inexplicable indigenous iconography (statues, drawings, photographs), and figurines of children—mostly pudgy blond girls riding pink ponies and unicorns. In hotel lobbies and shopping centers, there are no neon lights, touchscreen directories, or device-charging stations. Instead, it’s normal to come upon animals made of plastic and plaster—horses, pink flamingoes, black panthers—on display.

At the Stadthaus, the festival’s hub, a table full of red pens and two makeshift cardboard cases labeled “used” and “new” welcomes attendees, reminding us that despite this foray into non-digital contact with cinema and cinema-goers, the pandemic isn’t over. In fact, entering any physical space here means going through a series of unwieldy check-in steps, such as using the red pens to fill out printed forms with personal details, offering one’s proof of vaccination up for meticulous inspection and using the indefatigable Luca app, which, as one festival employee put it, “is a great app, but sometimes it doesn’t work.”

The thrill of watching films back to back in an actual theater isn’t complete without an audience of strangers. The screenings at this year’s IFFMH were very sparsely attended, as if only a handful of critics had managed to come out alive from the multi-tasking irritation of pandemic checkpoint rituals, and the rest of the city hadn’t received the memo that streaming isn’t quite cinema and theatres were open for business again. This meant that one of the most recognizable feelings of covering a festival, the anxiety of not making it inside, was absent. Instead, there was the depressing certainty that the room wouldn’t be filled to capacity, and one would be surprised to have to share a row with a neighbor or two.

Still, the festival, which ran from November 11 to 21, featured a handful of wonderful discoveries that, like the festival’s in-person experience mid-pandemic, are refreshing reminders of just how pleasant physicality can be. Films like Claire Simon’s I Want to Talk About Duras, which fictionalizes transcripts from interviews between Yann Andréa (Swann Arlaud), Marguerite Duras’s young gay partner, and journalist Michèle Manceaux (Emmanuelle Devos), into superbly cinematic dialogue sequences. The sharpness of the dialogue stems from the “realness” of its source, but it’s the mixture of the astonishingly nuanced acting and the physical elements surrounding the characters that cloak the words in credibility and poetry.

With I Want to Talk About Duras, Simon strips cinema to its bare essentials, not unlike Duras’s approach to literature and film. Two people speak, smoke, drink tea, and occasionally ignore a telephone that rings. There has been love at some point, but now we only have ashes, resentment, and the emancipatory latency of language. It’s Duras calling. We never actually see her, apart from a few archival inserts that serve as evidence of her domineering character. Namely, her control over words, control over life, control over Yann, to whom she’d say things along the lines of him not being a homosexual and him not wanting to have beef for dinner.

The film transports us to a cinema of analog, even psychoanalytic, simplicity. Yann does most of the talking and Michèle only intervenes when it counts, when the one who speaks should be held accountable for what he says. When Michèle listens, she does so in the most active of ways. We can almost see her caressing Yann’s words with her eyes, absorbing the smoke that comes out of his mouth with her every pore. Duras is physically downstairs but a solid specter in the middle of the room, haunting scenes to the point that the dialogue takes a Durasian tone. She could have written these scenes herself. And, in a way, she did.

In this cinema of substantial things, we can almost feel the piercing substance of words and the thickness of cigarette smoke, as well as Yann’s wooly turtlenecks and heavy leather vest, Duras’s sofa shawls and mahogany furniture. The props are bulky, requiring much labor for the characters to handle: the BASF tape recorder with its cumbersome buttons, the mic with the spongy head, the colossal typewriter, whisky bottles that are weighty even when they’re empty, and the black rotary telephone that makes the entire house tremble when it rings.

The film brings new understanding to Duras’s work, particularly when it comes to novels like Blue Eyes, Black Hair, whose plot revolves around the encounters of a gay man and a straight woman who sometimes leaves to have sex with the straight man that the gay man yearns for, and her 1981 tour de force of a film The Atlantic Man, starring Yann Andréa himself. Simon’s visual language also uncannily mimics the sensuality of Duras’s oeuvre, all while painting a terribly negative portrait of her personality as a control freak with abusive tendencies.

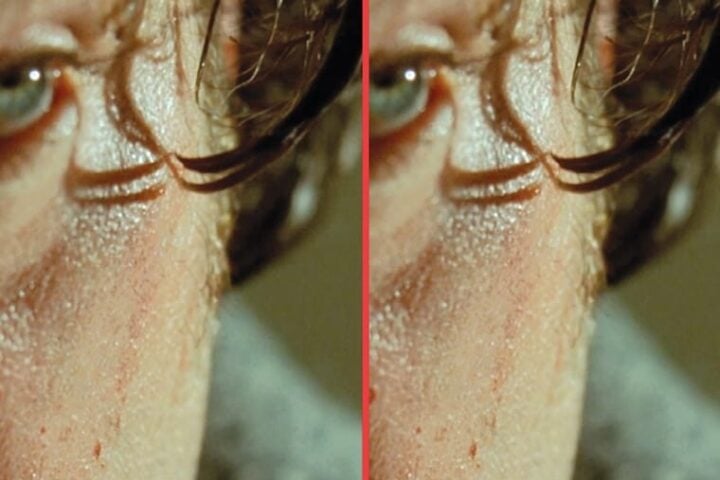

Filmmaker Andrea Arnold also plays up cinema’s remarkable ability to express senses such as smell and touch out of its inability to provide a direct experience of them in Cow. From the start we’re in the domain of the viscous. The first sequence captures the birthing of a cow, swaddled in an organic mantle of milky film, pulled from the mother out into the camp of horrors otherwise known as a dairy farm that will be its home. The little cow is so stunned by the discovery of the world that it looks as though it may already be dead.

But not so fast. Automated contraptions, cages, and burning irons await this and other animals. The viewer remains in the haptic register of gooey and grimy substances (dripping udders, slimy tongues, soiled skin, muddy hooves) throughout, as the camera rarely leaves the vicinity of cows’ bodies, particularly their faces. And all the while, humanity is reduced to that which—slowly and almost perversely—only invades, instrumentalizes, and kills.

The focus on the cows’ bodies, which tend to take up the entirety of the frame, along with the traces of their violent relations with their environment, brings out the animals’ sensibility, perception, sentience. The presence of human beings is felt through their disembodied voices and the naturalized cruelty of their actions. At one point, a man sticks a thick needle into a cow and says, “Good girl.” Arnold builds the portrait of beings trapped in the most horrific forms of waiting—for death, surely—little by little, avoiding the animal rights didacticism of many well-intentioned but less than cinematically compelling documentaries.

Throughout, the lingering camera gaze, whether fixed or moving, is interested in one thing and one thing alone: a cow’s face, which stares back at the lens and, at times, moos at it. In the process, a kind of affective connection is formed between animal and the cinematic apparatus—the kind that the slickest drone shot would, of course, never manage to capture.

In Cow, the camera has character, a vision, and maybe even an argument, though it’s one that we aren’t completely sure of. Or, in any case, it’s one that doesn’t beat us over the head. Unlike films that are much more obviously interested in delivering a useful message through the recognition of an animal’s torment, such as Victor Kossakovsky’s Gunda, Arnold’s more mysterious documentary forces us to keep looking and find out what exactly the cows want to tell us through the placidity of their gaze and, by extension, the camera’s own.

The International Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg runs from November 11—21.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.