Sérgio (Sérgio Coragem), the Portuguese protagonist of Pedro Pinho’s I Only Rest in the Storm, goes to Guinea Bissau to write an impact report of a road-building project. There he encounters many extraordinary individuals that exist mostly to conspicuously challenge age-old European prejudices about Africa. And yet, no one really causes Sérgio to question his presence in their world. In Pinho’s tale, modern-day colonial arrangements continue to pitch West Africa as a Las Vegas-like playground for white men to exploit.

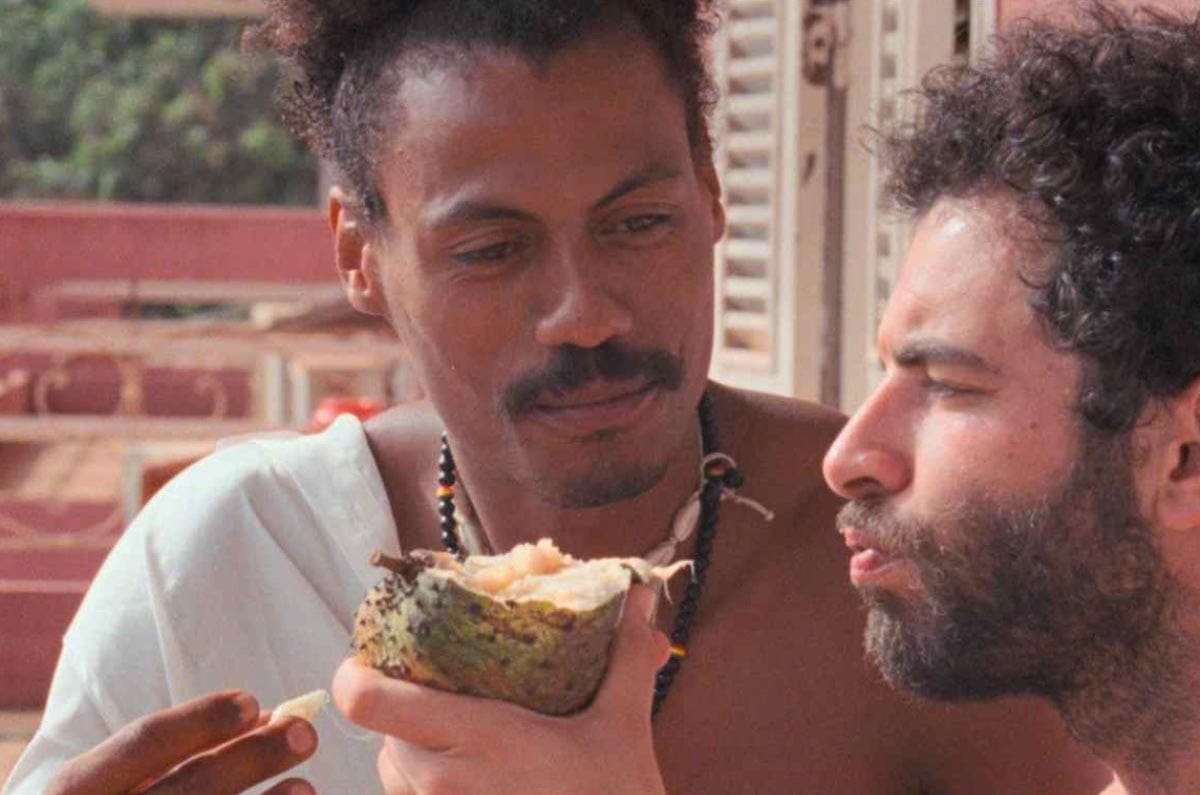

Everyone would appear to be suspicious of Sérgio, a self-righteous normie who roams around his new surroundings as if suffering from melancholia. Of course he’s sexually drawn to Black bodies, and his two main objects of attraction in the film are two especially transgressive types: a non-binary Brazilian exile, Guilherme (Jonathan Guilherme), and a socially conscious bar owner, Diára (Cleo Diára), whom he meets as she’s trying to escape a man following her through a market. Together, they dance, kiss, exchange erotically charged barbs, and have sex.

Though Sérgio keeps seeking refuge in Guilherme and Diára’s hedonism, as if trying to escape the sterility of his work environment, he never snaps out of a depressive state. Maybe, like us, he’s suffocated by the didacticism that everyone around him is prone to. Whatever the post-colonial lessons are, I Only Rest in the Storm’s characters articulate them too evidently, as if preemptively justifying the making of a film in or about “Africa” on the condition that the white man’s presence is relentlessly denounced. The filmmakers are obviously critical of the colonizer’s mindset, but they’re so adamant about making sure that we know their stance that almost every sequence here is structured around a kind of moral self-disclosure.

The original title of I Only Rest in the Storm is O Riso e a Faca, which literally translates to The Laughter and the Knife, and it establishes the kind of binarity that reflects the film’s shortcomings, as it never quite goes beyond the pitching of oppositions. In one scene, a West African person wonders if it’s true that in Portugal toilet water is good enough to drink and, in response, Sérgio asks if all West Africans can have three wives. This is also evident in the necropolitical violence of Sérgio’s road-making project (he’s not allowed to offer his water bottle to a thirsty local, because “rules are rules”), which is simplistically contrasted with the queer debauchery of the parties he attends with Guilherme and Diára, where sharing is caring.

Pedagogy even has to share space with the carnal frisson of the dance floor, with partygoers chatting about the colonial aggression of the Portuguese and resistance to it. And a sequence where locals are seen prepping goats to be slaughtered becomes an opportunity for Sérgio and Guilherme to fight over which of the goats they would choose to save: a black or a white one. Of course the white man picks the white goat and the Black person picks the black one.

I Only Rest in the Storm’s on-the-nose educational thrust reaches its climax when Sérgio tells Diára that he refused a bribe of 150 thousand Euros to rush his road development report because corruption is disgusting. She becomes outraged since what’s actually disgusting is people being cursed because of where they were born and not having their basic needs met. Elsewhere, she tells him that he has “no idea what it is like to be me” after chastising him for not caring about the working conditions of sex workers, the well-being of women in Guinea Bissau, human trafficking, and clean water for everyone.

It’s only in the rare instances when Pinho and co-writers Miguel Carmo, Paul Choquet, and Luís Miguel Correia take a close look at colonial relations but refrain from indicating which side they’re on that the film succeeds. That is, when someone, instead of starting a sentence along the lines of “After the Europeans came to the African coast…,” says something that guides rather than instructs. Like in an unexpected, and deliciously aimless, sequence toward the end of the film when, randomly, Diára asks Sérgio to watch her have sex with another man. The voyeurism, scripted by the woman’s own desire, organically leads to a bisexual threesome, with the white man’s body sandwiched by the Black ones, finally reduced to their plaything.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.