Its witnessing of Choe’s journey is delivered in no linear fashion, perfectly matching the artist’s creative process and maniac persona in its editing style.

The film reads like a desperate attempt for thriller legitimacy that over-borrows every cliché associated with the genre.

As is the case with most blatantly one-sided documentaries, the film can feel like one long in-house advertisement.

Lbs. is predictable, repetitive, and counts on indie-movie music to move the story along.

Easier with Practice knows that extracting authentic vulnerability from puritanical white bodies can be an impossible project.

While Johnny Weir’s queerness is never verbalized, the film is inevitably about that.

The film is a beautiful but stiltedly put-together tale of two women who love—and leave—each other throughout their entire lives.

When it remembers that it needs to deliver its green message, Big River Man sometimes gets too didactic.

The film’s first half is a refreshing portrait of an idyllic elsewhere that seems to have escaped globalization’s commodify-or-die edicts.

In 2009, it seems both sad and silly to aim for the mediocrity of sitcom laughter.

I wish I could say the film was about the homoerotics of phallic compensation, pathological American individualism, or the relationship between analyst and analysand.

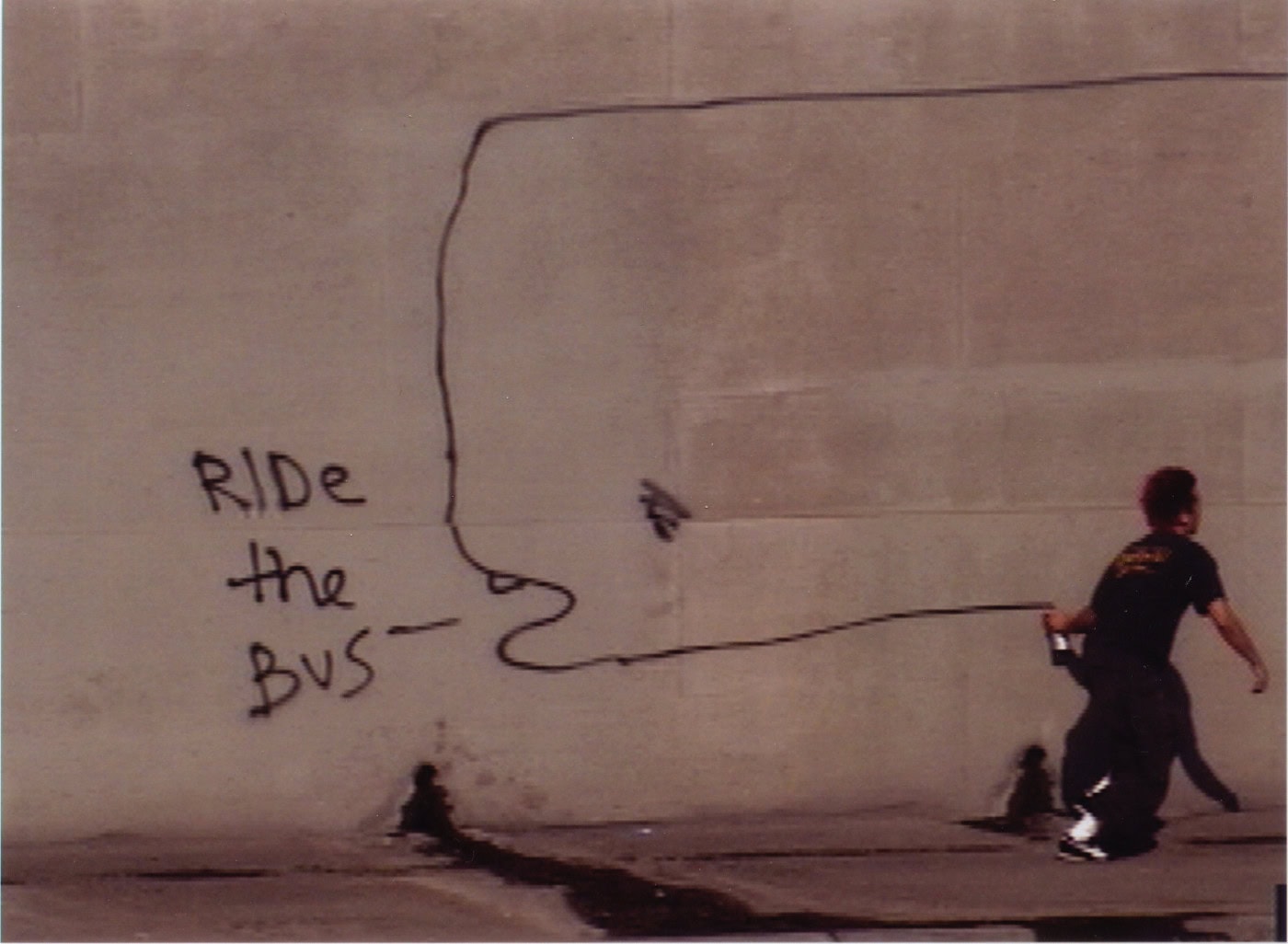

The Los Angeles of Spread is the Los Angeles of the collective unconscious: a playground for all things ersatz.