Despite its title, Richard Linklater’s breezily entertaining Nouvelle Vague doesn’t seek to offer us a broad overview of the French New Wave’s inception. As the film opens, the movement is already well underway: François Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard) is gearing up to premiere The 400 Blows at Cannes, and just about every other Cahiers du Cinéma critic except for Jean-Luc Godard (Guillaume Marbeck) has forayed into making features. Instead of depicting Godard as a capital-G great man who singularly embodies the spirit of the French New Wave, Linklater sees him as the last voice to join the chorus, legitimizing its rallying cry.

Nouvelle Vague charts the production of Godard’s monumental 1960 film Breathless, and it’s during the first act where Linklater’s film feels the most like a conventional biopic. The most famous quotes uttered by the critics turned filmmakers of the French New Wave just pour out of them in casual conversation, and theirs is the same kind of effortless philosophizing that so many Linklater characters are prone to, but it’s still hard to shake that these moments are drawing on film history in ways that exist to flatter cinephiles.

In one scene, Godard drives to Cannes through a row of trees awfully similar to those that Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) drives through in the opening of Breathless. The moment is familiar from so many biopics, with the subject accidentally stumbling upon inspiration for what the audience recognizes as one of their iconic creations.

Fortunately, once production on Breathless goes into full swing, Nouvelle Vague’s sentimentality falls by the wayside. What follows is a largely cut-and-dry account of the production, which thrives on sparseness. The numerous famous quotes injected into the dialogue slowly depreciate in significance, as it soon becomes clear that Godard is intentionally speaking in aphorisms—to the point of exhausting everyone around him.

Written by Holly Gent, Vince Palmo, Michèle Halberstadt, and Laetitia Masson, Nouvelle Vague offers little profundity about Godard’s directorial decisions, keeping the man psychologically opaque behind his iconic sunglasses, and to the point of absurdity. The logic, it seems, is to place us alongside characters who are yet unaware that they’re in the presence of genius.

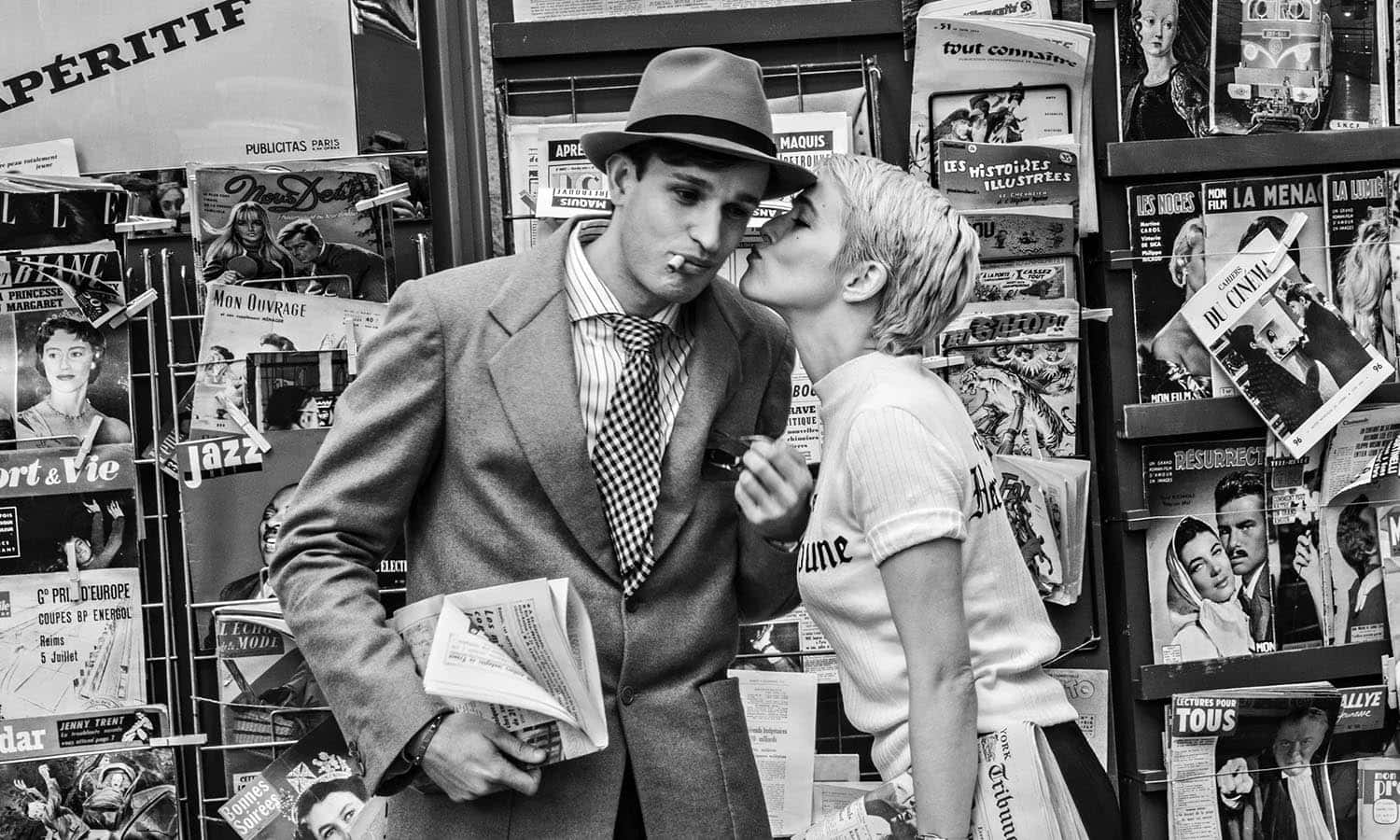

The biggest points of conflict that arise in the film are over producer Georges de Beauregard’s (Bruno Dreyfürst) and actress Jean Seberg’s (Zoey Deutch) increasing frustrations with Godard’s freewheeling approach—for flippantly burning money on half days and unused stuntmen, and for disregarding the actress’s process. Just as Godard seems to shrug these issues off, so does Nouvelle Vague, and the tensions between the creatives remain at a simmer.

This gives the film a low-stakes hangout quality characteristic of Linklater’s work. Part and parcel of that approach is Nouvelle Vague’s refusal to overinflate the significance of Breathless as its production comes to a close. The way that Godard shoots down his team’s attempts to celebrate is a comic reflection of Linklater’s insistence on not playing up how Breathless would become one of the most consequential moments in cinematic history. Which is to say that Nouvelle Vague sets out to see the production of Godard’s film as those on the set saw it: as a wacky couple of weeks spent working alongside a nutjob director.

There’s an apparent contradiction between the radical spontaneity that Godard chases throughout the making of Breathless and the more conventional narrative approach of Linklater’s film, though spontaneity was perhaps always incompatible with the nature of this project. Still, there’s pleasure to Nouvelle Vague’s winking affection for Breathless, as evidenced by the decision to shoot the film on 35mm black-and-white stock, complete with cigarette burns, and the crackles and pops in the sound, even if that’s not enough to ultimately elevate Nouvelle Vague beyond a pleasantly slight love letter to the French New Wave’s origins.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.