![]() The inaugural release of Shout! Factory’s new line of Hong Kong films long blocked from American distribution due to rights issues, The Jet Li Collection presents five of the martial arts star’s earliest and most beloved hits. Though Li had been a star in mainland China since his film debut in 1982’s Shaolin Temple, he found wider success a decade later with his lead role in Tsui Hark’s Once Upon a Time in China series. The films in this set all came out between 1993 and 1994, a super-concentration of hits that made the actor the new king of Hong Kong’s action scene.

The inaugural release of Shout! Factory’s new line of Hong Kong films long blocked from American distribution due to rights issues, The Jet Li Collection presents five of the martial arts star’s earliest and most beloved hits. Though Li had been a star in mainland China since his film debut in 1982’s Shaolin Temple, he found wider success a decade later with his lead role in Tsui Hark’s Once Upon a Time in China series. The films in this set all came out between 1993 and 1994, a super-concentration of hits that made the actor the new king of Hong Kong’s action scene.

Compared to Hong Kong mainstays like Jackie Chan and Yuen Biao, who blended serious technique with comedic timing, Li harked back to the era of stoic warriors like Bruce Lee and Jimmy Wang. That makes him an odd fit at first glance for Cory Yuen’s two 1993 wuxia comedies about Chinese folk hero Fong Sai-yuk. In both movies, Li’s Fong largely wants little more from life than to hone and demonstrate his kung-fu skills, only to find himself embroiled in everything from arranged marriages to political intrigue.

The plot convolutions tend to play against Li’s strengths, and, indeed, Josephine Siao steals significant portions of both Fong Sai-yuk and Fong Sai-yuk II from under the lead as Miu Tsui-fa, Fong’s mother. Hectoring and melodramatic, Miu also has her own kung-fu skills and enters a local tournament along with her son. Disguised as a man, Miu ends up catching the eye of the organizer’s wife (Sibelle Hu), and her frantic attempts to dissuade the woman while also allowing her to save face proves a far more entertaining storyline than Fong’s inadvertent conflict with a cabal seeking to overthrow the Qing dynasty.

While Li often looks more impactful in his moves than his comic peers, he also has a lithe, fluid movement that Yuen incorporates into some imaginative scenarios. This is particularly evident in the first film’s climax, in which Fong and a villain duel in a crawl space beneath a public platform and Li, though curled up nearly into a ball, glides around the area and uncoils like a snake to dart out a kick or punch before bunching up again. If Li’s comedic chops don’t quite measure up to his physicality, the Fong Sai-yuk movies are still prime early-’90s Hong Kong entertainment, and the supporting casts bring the humor when the star gets overly serious.

Yuen and Li reteamed for the contemporary-set The Bodyguard from Beijing, which, as the title suggests, is a riff on the Kevin Costner/Whitney Houston hit from the previous year. Here, a political element is added as Li’s mainland bodyguard is assigned to protect Michelle (Christy Chung), the girlfriend of a seedy corporate giant after she witnesses the murder of a Hong Kong businessman. The collision of Chinese and Hong Kong values adds a compelling wrinkle to what is otherwise a standard action-romance from the region’s Heroic Bloodshed heyday, creating as much tension between the two leads as their budding attraction to each other.

Sadly, this is one of the lesser achievements in both Yuen and Li’s filmographies. The action sequences are spread too far apart, and each feels too short to compensate for the repetitive scenes showing the longing between the main characters. Like many Hong Kong romances, the film has a hazy, gauzy look, as if a length of gossamer had been pulled over the camera lens, and that soft image quality undermines the intensity of the occasional shootouts.

Far stronger is Gordan Chan’s First of Legend, a remake of Fist of Fury, the 1972 action classic that catapulted Bruce Lee to superstardom. Set in the foreign-occupied Shanghai International Settlement during the First World War, Chan’s film wastes little time establishing a web of intrigue that involves imperial Japanese forces, native collaborators, and Chinese nationalists vying for control over the territory long before the full Japanese invasion of the 1930s.

Li’s Chen Zhen is a martial artist drawn into this political minefield when his teacher dies in a fight with the sensei of a Japanese dojo—a duel that Chen suspects was rigged with the help of poison. Intriguingly, though the villains are Machiavellian imperial leaders, the film ducks a simplistic view of resistance against Japanese occupiers in favor of a nuanced pre-WWII depiction of at least some cultural exchange: Both the Japanese sensei (Jackson Lau Hok-yin) and ambassador (Takanashi Toshimichi) express open admiration for Chen’s honorable behavior, and Chen himself has an affectionate relationship with Japanese classmate Mitsuko (Nakayama Shinobu), whom he defends from friends and comrades.

Throughout, Yuen Woo-ping’s realistic fight choreography stands in stark contrast to the more elaborate, wire-based stunts that defined many of Li’s vehicles around this time. It’s here that one gets a full appreciation of Li’s elegance as a physical performer. In fight scenes, he’s particularly compelling for the way his character curves around an enemy’s strikes.

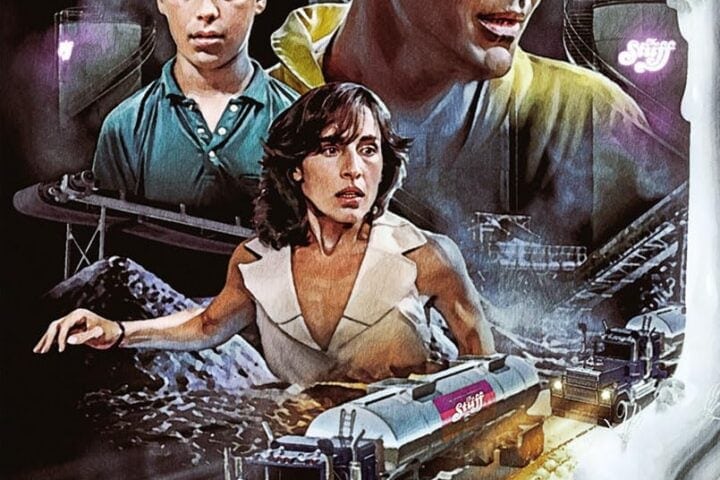

Yuen was also a master of wire-fu stunts, as evidenced by his directorial effort from 1993, Tai Chi Master, which is the highlight of this set. Initially, the film plays as a broad comedy in the vein of the Fong Sai-yuk movies. Jun Bao (Li) and Tian Bao (Chin Siu-Ho) are rambunctious monks whose antics verge on outright slapstick, with Jun Bao, given his overriding desire to genuinely learn from his master, as the straight man to his more anarchic friend.

Upon their expulsion from their temple, though, the pair find themselves at a crossroads when asked to work for a local warlord. Jun Bao refuses to use his talents for evil, but his friend accepts, driving a wedge between the two that ends with both on either side of a civil war. The shift into drama underlines Li’s strengths at projecting characters’ inner resolve, and the fight scenes showcase the incredible athleticism of both the star and Michelle Yeoh, who becomes a dominant player in the film’s second half as a leader of a regional resistance movement. Better than nearly any other Li film, Tai Chi Master unites all the best attributes of his most beloved movies into something that manages to be funny, thoughtful, and dazzlingly choreographed.

Image/Sound

Shout! Factory’s transfers all come from new 4K restorations, and they’re revelatory. All five films sport healthy grain distribution and stable blacks. There are instances of debris and lapses in image fidelity, and some flaws are endemic to the movies themselves (The Bodyguard from Beijing, for one, suffers from loss of detail due to its over-lit cinematography), but overall, the contrast levels, color depth, and textures are consistently strong.

The mono soundtracks are free of hissing or pops and have none of that faint, tinny quality that some of these films have long suffered on home video releases of dubious legality. The dialogue is crisp and centered, while music cues and sound effects ring out clearly.

Extras

Shout! Factory supplements these films with a treasure trove of bonus material. Each movie gets a new commentary track by film critic James Mudge, and a host of new and archival interviews with filmmakers and academics situate the movies in the larger Hong Kong cinema scene of the ’90s. Tai Chi Master gets the finest extras, including behind-the-scenes footage of the set where much of the film takes place and a new tribute to Michelle Yeoh featuring personal and critical appraisals from a host of critics and peers such as Cynthia Rothrock.

Overall

Shout! Factory puts its best foot forward for its new line of Hong Kong classics with a slate of beautiful transfers and a wealth of extras for some of Jet Li’s most entertaining movies.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.