![]() Though it didn’t inaugurate the French New Wave, François Truffaut’s 1959 debut feature, The 400 Blows, did herald the true arrival of the movement, netting the critic turned filmmaker a best director award at the Cannes Film Festival and rave reviews around the globe. Drawing heavily from his own childhood, as well as inspiration from Italian neorealism and 1950s Hollywood melodramas such as Rebel Without a Cause, Truffaut charts the antics of bright but unruly misfit Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud), who, without a sense of purpose, consistently gets into trouble with teachers and his parents.

Though it didn’t inaugurate the French New Wave, François Truffaut’s 1959 debut feature, The 400 Blows, did herald the true arrival of the movement, netting the critic turned filmmaker a best director award at the Cannes Film Festival and rave reviews around the globe. Drawing heavily from his own childhood, as well as inspiration from Italian neorealism and 1950s Hollywood melodramas such as Rebel Without a Cause, Truffaut charts the antics of bright but unruly misfit Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud), who, without a sense of purpose, consistently gets into trouble with teachers and his parents.

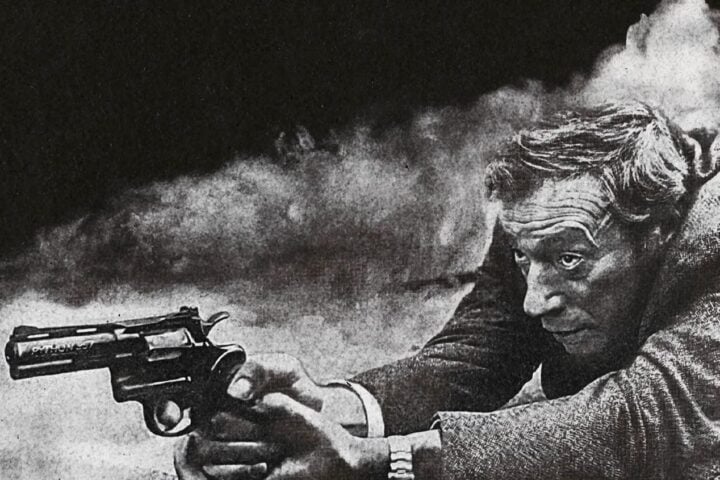

Truffaut’s kinetic and restless camera style is keyed to the boundless energy of youth, and even the most carefully blocked and framed shots have a feel of spontaneity to them. But The 400 Blows ultimately belongs to Léaud. Flashing hints of innocence and yearning that recall James Dean’s smoldering intensity, the 14-year-old actor makes it clear that Antoine is no mere delinquent, but a sensitive, inquisitive soul whose intelligence is too empathetic and artistic to be compatible with a model of education designed to make humans feel like cogs in the machine of the state. The film’s last shot, of the boy fleeing a correction center to run to the nearby coast before turning back with an ambiguous, trapped look on his face, is among the most searing single images of the entire Nouvelle Vague.

Truffaut would revisit Antoine sporadically over most of his career, using the character to comment on both his experiences of aging and shifting interests as a filmmaker away from his early polemicism toward a more crowd-pleasing accessibility. Cleverly, though, Truffaut self-critically comments on the latter by foregrounding Antoine’s arrested development thanks to a thwarted childhood spent in correctional facilities. Appearing at various stages of adolescence and adulthood, Antoine always seems to be consciously attempting what he thinks is normal behavior that he’s gleaned from movies and people-watching. This effectively makes him an actor in his own life, and Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel films amusingly reflect this artificiality.

In the 1962 short “Antoine and Colette,” for example, the young man makes his first courtly moves toward a girl, Marie-France Pisier’s Colette, but he tries so hard to say the right thing at all times that he comes across as overly rehearsed and too forward. Often speaking over Colette while feigning gentlemanly respect, Antoine slowly erodes the girl’s interest in him. The battle-of-the-sexes repartee makes it easy to mistake “Antoine and Colette” for a film by Éric Rohmer, but Truffaut’s fingerprints are keenly felt in the warmheartedness of the short’s perspective on young love, as well as in the freewheeling camera style.

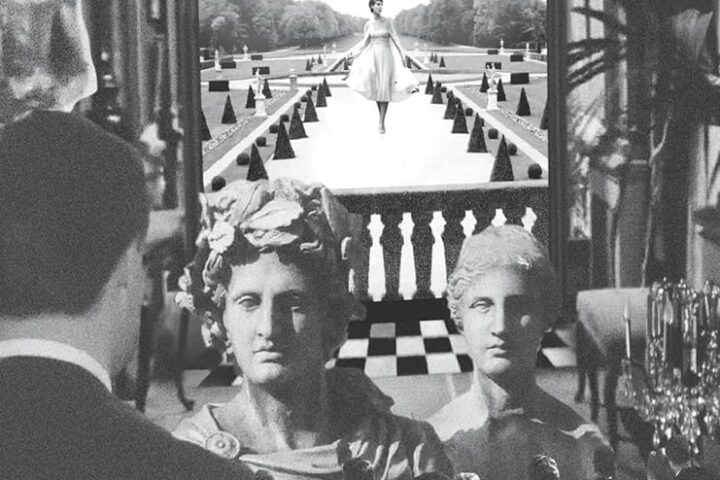

Truffaut returned to the life of Antoine in 1968’s Stolen Kisses, and pointedly the film’s only acknowledgement of the political turbulence in France at that time is an opening shot of the Cinémathèque Française closed during the period of founder Henri Langlois’s state-mandated firing. As many of his peers were attempting to capture the growing labor and student protests, Truffaut peered in on Antoine in the key of a screwball comedy as the man tries to land a steady job and also commit to a series relationship with girlfriend Christine (Claude Jade).

And yet, there’s something fitting about this ostensible retreat from the moment. The screwball era arose during the Great Depression as a means of lampooning the self-absorption of the idle rich, and here we see Antoine so wrapped up in the ongoing effort of gaining a sense of self that the outside world barely exists. Truffaut wrings humor out of the young man’s haphazard entry into the world of being a private detective and the subsequent affair he begins with the wife (Delphine Seyrig) of a client, reorienting the character’s once-tragic disconnect from a sense of normalcy into a comedy of manners hinging on his awkward, stunted behavior. In one memorable segment, Antoine gets completely distracted by a magician while on the job, the years melting off his still-young face as he gazes at simple tricks with total wonder.

In ways both intended and unavoidable, 1970’s Bed and Board retreads much of the same ground as the prior two films—a reflection of Antoine’s ongoing failure to launch but also a show of diminishing returns as the character again finds himself driven by his wandering eye and fear of commitment. An initial facade of the man and Christine in a state of domestic tranquility as they expect their first child crumbles when Antoine meets Kyoko (supermodel Hiroko Berghauer), the attractive daughter of a client. The film has its charms—including a hysterical scene of the autodidact Antoine attempting to understand his attraction to Koyoko by sitting in bed with Christine reading a book titled Japanese Women—but the general shape of the narrative is merely a more sedate rendering of Stolen Kisses’s comedy of remarriage.

The final Antoine Doinel film, 1979’s Love on the Run, is even more derivative, with much of the runtime devoted to clips from the earlier movies. But where Bed and Board felt occasionally rudderless, here Truffaut steers his protagonist’s stasis more purposefully. The heavy use of old footage puts the viewer in Antoine’s perspective as he relives memories with both fondness and regret. By the same token, the director at last moves outside of Antoine’s headspace to give more input to the women of his past and present, who force the immature man to own up to the emotional toll his obliviousness and selfishness has taken on them.

Their criticisms are righteous but also constructive, and the women all share a desire to see Antoine actually grow into the person they thought he could be. Indeed, it’s by dropping his guard and listening to them that he begins to break out of his stasis. That restless glint in Antoine’s eyes over a 20-year period finally dims as he accepts the possibility of maturing even if it means never attaining an ideal he never learned to fully conceive of, much less grasp.

Image/Sound

On both the video and audio fronts, the Criterion Collection’s UHDs, sourced from 4K restorations, are significant upgrades from the DVDs included on the label’s 2002 set. Each transfer boasts healthy grain distribution and clear detail. The early black-and-white films have stable contrast and rich black levels, while the later movies present their color photography in all their radiance, especially the bold use of green and yellow. The Néstor Almendros-lensed Bed and Board and Love on the Run look particularly rich in 4K, with each subtle fluctuation of available and artificial light captured minutely. The lossless mono soundtracks for all the films lack any discernible instances of hiss, popping, or dropout. Dialogue is consistently centered over street noise and the occasional burst of music.

Extras

Criterion ports over all of the extras from its 2002 DVD set, including the audio commentaries for The 400 Blows, one by scholar Brian Stonehill and one by Truffaut’s longtime friend Robert Lachenay, as well as the one for Truffaut’s 1957 short “Les Mistons” (which also gets a sparkling 4K upgrade) by Claude de Givray, who co-wrote Stolen Kisses and Bed and Board. Lachenay and de Givray’s tracks are especially noteworthy for the men’s insights into Truffaut’s personality and methods over the course of his life and career. The set also includes audition tapes of the young actors in The 400 Blows and newsreel footage of Truffaut and Jean-Pierre Léaud over the course of their partnership in interviews and press conferences.

Among the more interesting archival clips are ones that show Truffaut’s advocacy for Henri Langlois and participation in the boycott of the 1968 Cannes Film Festival, standing alongside the more polemical Jean-Luc Godard in voicing his objection to the government’s cultural and political actions. A booklet contains reprinted essays from Truffaut himself as well as critics such as Andrew Sarris that unpack individual Antoine Doinel films and the series as a whole.

Overall

François Truffaut’s celebrated saga receives a major A/V upgrade from Criterion, with transfers worthy of screening at the Cinémathèque Française.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.