Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck’s Freaky Tales is an ode to 1987 Oakland rife with references to (and cameos by) various music and sports icons of the city’s underdog era. The film illustrates the eclecticism of Oakland via an anthology of four stories connected by little more than characters from each segment briefly occupying the same spaces as the narrative baton is handed off between teen punks, wannabe rappers, a thumb-breaking debt collector trying to go straight, and Golden State Warriors player Sleepy Floyd (Jay Ellis).

Nakedly wearing its cinematic influences on its sleeve, Freaky Tales suggests Pulp Fiction by way of Repo Man. In the first segment, “Strength in Numbers,” a trio of teenage punksters (Ji-young Yoo, Marteen, and Jack Champion), high off of seeing The Lost Boys at the Grand Lake Theatre, go to the iconic all-ages music venue Gilman Street, where they catch a set from the punk band Operation Ivy. Throughout, the camera lovingly scan the walls for the accumulated band posters, anti-Reagan graffiti, and house rules that seek to foster an inclusive space.

Freaky Tales is a spirited celebration of people’s resistance to racism. Soon, a group of local neo-Nazi skinheads invade the Gilman, and their arrival signals the film’s shift from a lighthearted, naturalistic coming-of-age story into an action comedy redolent of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, albeit one shot through with hard-R gore. Later, after Yoo and Champion’s characters lick their wounds and a street fight breaks out between the members of the Gilman punk scene and the neo-Nazis, the filmmakers flood the sequence with comix flourishes, like impact lines, and onomatopoeic sound effects of fists and blunt objects meeting neo-Nazis faces.

The next segment, “Don’t Fight the Feeling,” focuses on war of words in the form of a rap battle between West Coast hip-hop pioneer Too $hort (rising Bay Area MC Symba) and two teenage ice cream parlor workers, Entice (Normani) and Barbie (Dominique Thorne), who work on their verses as a release from their adolescent stress and the predations of their customers. Even when Too $hort swiftly resorts to sexist wordplay when squaring off with the pair, the growing confidence of Entice and Barbie’s verses turns what could have been a mean-spirited pile-on into a mutual demonstration of skill that wins the young women respect.

Boden and Fleck care to highlight the common communal values that this budding hip-hop sphere shares with the punk ethos captured in the first segment, while respecting the unique aesthetic and expressive properties of each. Compared to the dingy, lived-in vibe of the Gilman, the club where the rap battle occurs is far glitzier, awash in saturated red and blue lighting.

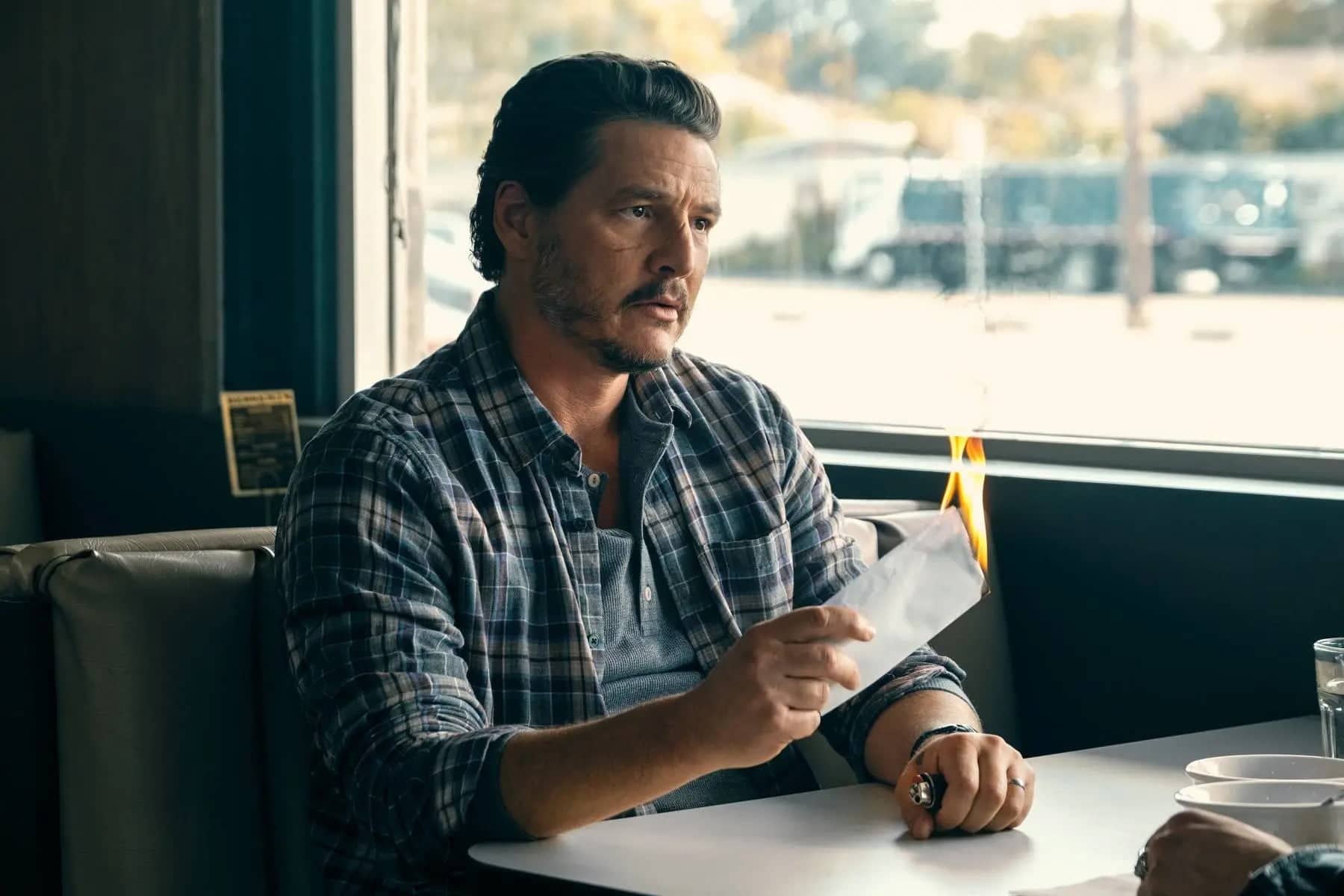

The final two segments feel less distinct from one another, not only for corkscrewing together narratively but for mining similar genre terrain. Both are revenge stories—one involving a thumb-breaking debt collector (Pedro Pascal) vainly trying to go straight, the other Sleepy Floyd seeking out those responsible for a grisly break-in at his home. “Born to Mack” cribs from Pulp Fiction’s Butch Coolidge plotline, and “The Legend of Sleepy Floyd” from kung-fu movies, with the filmmakers directing the action within them with far more fluidity and coherence than they did in Captain Marvel. Still, the segments lack the intimacy and observational nuances of the preceding ones, effectively turning Freaky Tales into a mere genre exercise.

At its best, the film is a love letter to the Bay Area underground music scene that would explode into the mainstream over the next decade. The eye for detail and open affection for young fans’ loyal support for local arts scenes are infectiously entertaining, and a righteous needle-drop of then-ascendant San Francisco exports Metallica is a passionate reminder of the critical role that the region played in fostering many of the biggest sounds of the ’90s.

For all of its spiritedness, though, Freaky Tales wants for the sense of invention that defines the films that it references and whose moves it often falls back on borrowing, as evinced by the recurring nods to Repo Man’s radioactive-green-glowing car and the many lampshaded mentions of movies such as The Shining and Enter the Dragon. It’s unfortunate that Boden and Fleck too often allow the elements of their film that feel most individualistic and unique to their interests to be drowned out amid visual and spoken gestures toward the work of others.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.