Ten years after Sinister, writer-director Scott Derrickson, co-writer C. Robert Cargill, and star Ethan Hawke re-team for another dimly lit foray into supernatural horror. The Black Phone replicates the same chilling highs and stultifying lows of the earlier film, with Derrickson again exhibiting a penchant for creating a suitably creepy atmosphere through subtly churning sound design, simple-but-spooky visual devices, and liberal use of atmospherically grainy 8mm footage. But like Sinister before it, The Black Phone also suffers from a repetitive structure, over-stuffed mythology, and under-explored ideas.

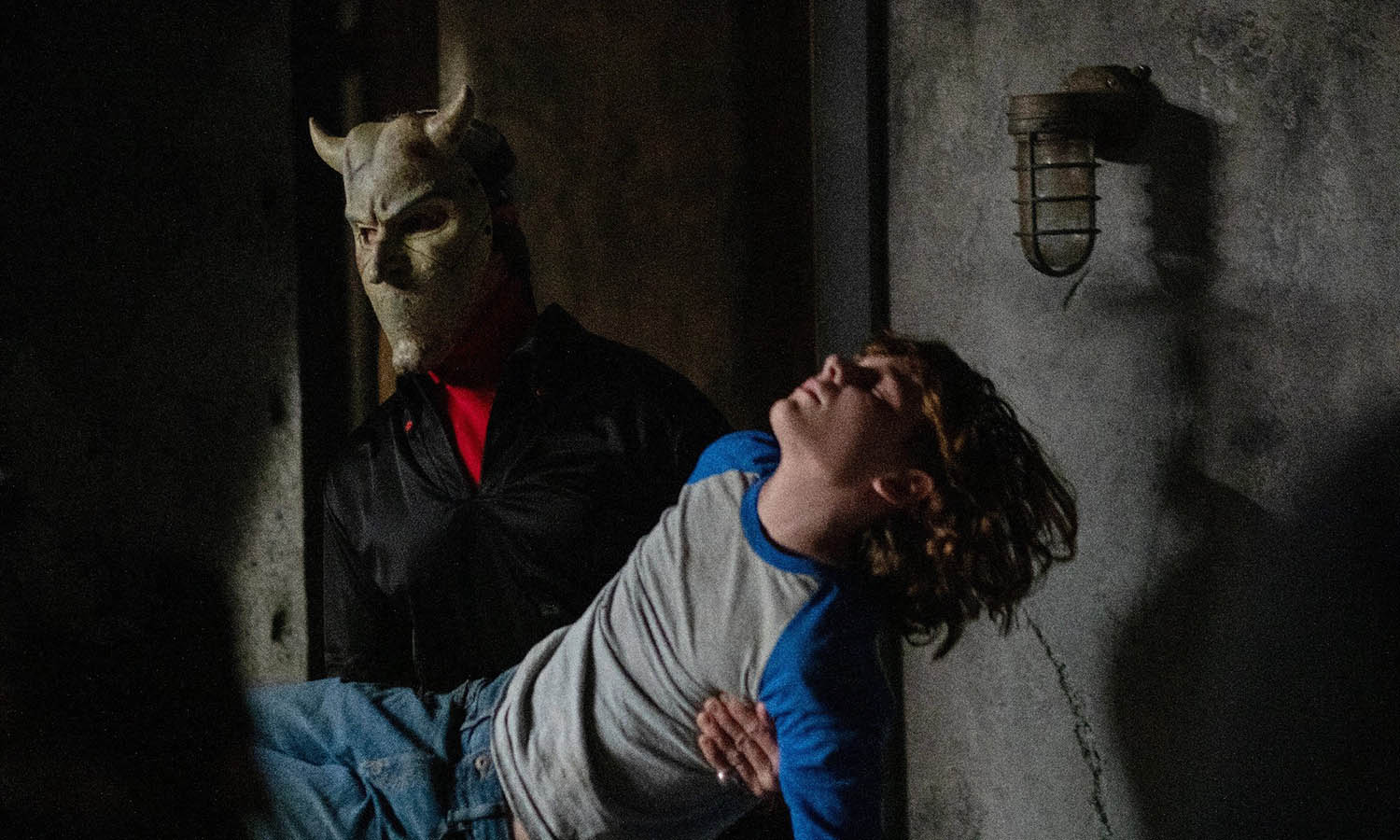

Derrickson and Cargill are adept enough at setting up rich, evocative horror concepts, but they don’t always know what to do with them once they’re in place. Take, for one, The Black Phone’s villainous central figure, a deranged serial child murderer known to the North Denver suburban community that he terrorizes as the Grabber (Hawke). Sporting a grotesque mask that melds the angular exaggerations of the Green Goblin’s helmet with Conrad Veidt’s permanent rictus grin from Paul Leni’s The Man Who Laughs, the Grabber is a genuinely frightening presence, made all the more unsettling by Hawke’s manic, against-type turn.

With his face at least partially obscured for the duration of the film, Hawke relies on his soulful eyes and a giggly, childlike voice performance (shades of Paul Dano’s Riddler from Matt Reeves’s The Batman) to suggest a pathetic, wounded little boy lurking behind the monstrous façade. Not long into the film, the Grabber kidnaps Finney (Mason Thames), a shy middle-schooler with a fondness for rockets who’s bullied at school and tormented at home by his abusive dad (Jeremy Davies). The dynamic between this deranged kidnapper and sensitive kid is a potentially rich one, but the film is, unfortunately, uninterested in exploring it.

Instead, Derrickson and Cargill’s screenplay—which is based on the short story of the same name by Joe Hill—load up the subplots, from Finney’s clairvoyant sister, Gwen (Madeleine McGraw), attempting to use her visions to find her sibling, to two local detectives (E. Roger Mitchell and Troy Rudeseal) investigating the case emloying less supernatural methods, to the Grabber’s cokehead brother (James Ransone) finding himself obsessed with solving the child disappearance cases, oblivious to the fact that his own brother is behind them.

The film doesn’t develop these ancillary characters so much as it toggles between them, repeatedly hitting the same plot beats. The filmmakers’ inability to deepen any idea beyond its initial conception is most vexing in their handling of the black rotary telephone that hangs on the wall of the dingy, soundproof basement where the Grabber keeps Finney locked up. On this phone, Finney receives otherworldly calls from the boys that the Grabber previously snatched and killed. This premise, though evocative, quickly becomes a rote plot mechanism. Each call suggests a video game cutscene, with each new cardboard-cutout NPC with a potted backstory giving Finney a mission to complete, from digging a hole beneath a hallway tile to removing a cable from the wall and using it to try to swing up to the window.

These dead kids, who appear to Finney in his room, pallid and bloody, provide the pretext for a few cheap jump scares as they pop up out of the shadows—jolting moments that disappear from the mind almost as soon as they’ve occurred. Meanwhile, The Black Phone’s one truly creepy and fascinating element—the Grabber himself—is oddly sidelined, spending much of the film shirtless, lounging in a chair in his kitchen, out of earshot from Finney. Derrickson keeps the Grabber’s background, motivations, and day-to-day life largely opaque, an understandable decision given that horror-movie monsters are usually scarier the less we know about them. Still, the choice to so frequently steer the film away from its own villain is baffling, especially when the places it does go are only occasionally compelling.

With its classic rock soundtrack, the film’s emulation of Carter-era suburbia lends a mock-Linklaterian hang-out vibe to the opening passages and provides an excuse for some nicely executed needle drops, including Pink Floyd’s “On the Run,” which is used to soundtrack a tense sequence before the climax. But that’s where it ends. The film doesn’t have anything to say about America in the ’70s, nor have the filmmakers even really attempted to capture the feeling of the times, instead deploying some nostalgia-baiting pop-culture references (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Emergency!) as if these were enough in themselves to evoke a bygone era. “The Seventies”—like psychic powers, child abuse, and talking to the dead—is just another disconnected concept bobbing around in the film, weightless and dispensable.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

This was like watching a Christian horror film.