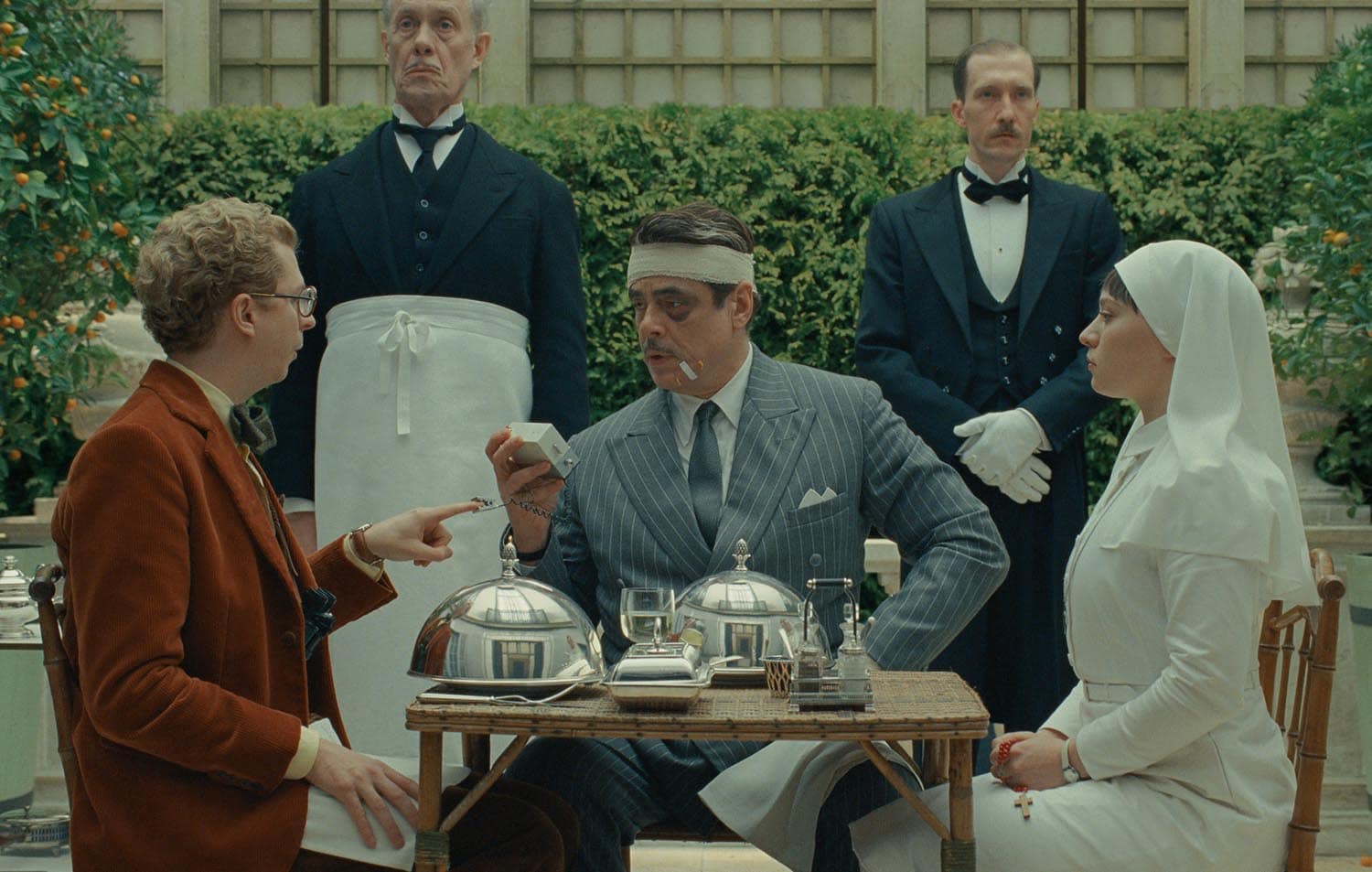

In Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme, an inclination toward pondering the divine goes hand-in-hand with the nearness of demise. The filmmaker arrives at this junction not because, as Christopher Hitchens might say, death causes religion. It’s through the sharpening of focus around what matters in life when its end feels imminent for Zsa-zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro), an international businessman who survives another assassination attempt by plane crash at the film’s outset. The sixth of such instances prompts him to reconnect with Liesl (Mia Threapleton), his estranged daughter living in a convent as a novitiate nun.

Families are often central to Anderson’s work, though he’s typically had clear sympathies with the younger members of these broods. Whether it’s the precocious overachiever Max Fisher in Rushmore or the trio of Whitman failsons in The Darjeeling Limited, the absence or neglect of parental figures directly contributes to the emotional misery of children. Even when rendered with full humanity, like the elder statesmen of The Royal Tenenbaums, Anderson still mostly refracts the struggles of his adult characters through the prism of their offspring.

That affinity, though, began to shift with the multi-generational narrative of 2023’s Asteroid City and solidifies in The Phoenician Scheme. Anderson is now as comfortable portraying the strivings and shortcomings of parents as he is their progeny. His partnership here with fellow girl dads del Toro and co-writer Roman Coppola intensifies that connection. They’ve made an exemplary “as the father of a daughter” work, turning the phrase that’s become shorthand for self-aggrandizement into a heartwarming appeal for prioritizing the next generation.

It’s only appropriate that Korda be a character as big as Anderson’s newfound alliance with the patriarchal position. Del Toro gets the meatiest leading role in an Anderson film since Gene Hackman’s Royal Tenenbaum, and Korda earns all the space he takes up among the expansive ensemble with his irresistible blend of grandiose self-regard and silver-tongued sardonic wit.

This grandiosity is also reflected in the camerawork, which is handled for the first time in a live-action Anderson feature by someone other than his longtime cinematographer Robert Yeoman. Director of photography Bruno Delbonnel still mostly keeps Anderson’s house style of smooth dollies and geometric compositions, but, especially at the start of The Phoenician Scheme, he disrupts Anderson’s proclivity for framing shots at a clean eye-level gaze on his subjects.

Delbonnel finds vantage points less common in Anderson’s work to both accentuate and diminish the characters’ humanity. He places the camera below Korda in several early scenes, bolstering del Toro’s towering figure to amplify the character’s larger-than-life qualities before he’s cut down to size. He also shoots from above, most notably as Korda recovers in a bath while the opening credits roll. Rather than situating the audience to look in on the Anderson’s dollhouse-esque mise-en-scène, as if the characters shared a similar stature, The Phoenician Scheme often places viewers above it to look down on the figures from a place of judgment.

This omniscient perspective could be a stand-in for Anderson’s purview of his creation, though the film’s most memorable sequences hint that they could represent an ethereal observer. A “Biblical Troupe” including Bill Murray as God pops up each time Korda cheats death once again, offering cryptic glimpses of his final celestial judgment. Whether this is heaven or a hallucination remains unexplained, but each successive surrealistic glimpse at his fate impacts the negotiations unfolding across his European business ventures.

These interludes are invigorating because they resist the sleekness that Anderson has turned into a hallmark. The Phoenician Scheme’s plot feels largely ornamental by the filmmaker’s standards as Korda, with Liesl and assistant Bjorn (Michael Cera) in tow, traverses the continent to renegotiate deals along more favorable financial terms. But to say the film is about the price of a bolt used in construction materials is like describing Moby Dick as a novel about whales.

Across The Phoenician Scheme, Korda attempts to haggle for a better rate with a series of partners: the bemused Prince Farouk (Riz Ahmed), basketball-loving brothers Leland (Tom Hanks) and Reagan (Bryan Cranston), an American shipping magnate (Jeffrey Wright), and a French nightclub owner (Mathieu Amalric). After approaching those tied to him through commerce, the tycoon must then face those related to him through blood: his Cousin Hilda (Scarlett Johansson) and Uncle Nubar (Benedict Cumberbatch).

The picaresque story gets a bit schematic as it plods along, an impression only intensified by on-screen titles showing Korda’s math to get to his targeted five percent cut. The globe-trotting adventure in The Phoenician Scheme proves more enriching when thought of like the Stations of the Cross for Korda. It’s a journey of humbling and mortification, all moving toward his successful operation and sacrificial offering. The morally dubious mogul moves toward realizing the titular business strategy by funding an ambitious infrastructure project to industrialize the fictional country of Phoenicia. But across these ersatz escapes, he’s also assembling something he can bequeath to Liesl besides material goods and beyond monetary value.

Korda’s real investment is in Liesl herself, an amassed inheritance that culminates and continues his life’s work. The Phoenician scheme, as fulfilled through her, can weather the winds of commerce and the weathering of time like the mythical bird capable of resurrection. A Bach cantata, which plays softly behind some of the duo’s most poignant interactions, summons images from a familiar rite of paternal passage in wedding ceremonies. A father’s greatest accomplishment is something he’s meant to give away.

Anderson never hints at autofiction in the story, yet it’s easy to draw a line between Korda’s revelation and the director’s stylistic maturation. There’s always been authenticity lurking under his artifice, but the raw emotion underlying The Phoenician Scheme peeks out at unexpected times. (Korda’s consistently bandaged face is but the most obvious visual manifestation of Anderson resisting his tendency for tidiness.) This sentimental streak still strains against the deliberate flatness of his actors’ line delivery, but a limited range of expression doesn’t preclude any soulfulness. It’s a revitalization, if not an entire rebirth.

For a film that’s never short on pithy verbal irony, The Phoenician Scheme’s most profound irony is embedded in its structure. A life and its work cannot be compressed and compartmentalized neatly into boxes, no matter how hard the protagonist or his creator might try. No dam that Korda funds or diorama that Anderson creates can withstand death. Building up a legacy is what ultimately matters for both men. Anderson may not preach this message as gospel, but the way he communicates it is indelibly graceful.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.