Guillermo del Toro’s veneration for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is evident across his long-awaited adaptation, allowing the film to stand tall among the many cinematic works adapted or inspired by the 1818 novel. The film is in del Toro’s wheelhouse as a sometimes ferocious examination of the thin, porous boundaries separating men from monsters. But it also leaves one with the impression that the filmmaker prostrates himself before his source material at the expense of consistently playing to his strengths.

At a prolonged 150 minutes, this Frankenstein can sag under the weight of del Toro’s fidelity to the events of Shelley’s Gothic novel. This means that the director does extensive table-setting before we get to the moment where Oscar Isaac’s Victor Frankenstein vivifies his monster. Kate Hawley’s costumes are ravishing, but it’s a very long and stodgy wade through the scientist’s early family life before del Toro unleashes the monster of his own imagination.

Del Toro does place the tale more squarely in the Victorian era, where scientific progress and strict morality butted heads. Frankenstein’s initial presentation of his re-animation theory draws jeers from his intellectual peers, requiring him to get craftier to test his ideas. Through a deal with an unsavory arms manufacturer, Henrich Harlander (Christopher Waltz), Frankenstein manages to get the funding necessary to kickstart the building of his humanoid.

The film begins heating up once Frankenstein becomes consumed by the work of realizing his project. Del Toro recontextualizes a figure whose labor frequently becomes a cautionary tale for scientific advancement gone off the rails. Here, the character’s monomaniacal energy reflects the creative process. As he orchestrates various discrete components that are needed to bring his big idea to fruition, it’s impossible not to think of del Toro marshaling his various collaborators toward a common goal. That Frankenstein also operates with a macabre sense of humor, not to mention undeniable joy, only reinforces the parallel.

It’s in each man’s singular vision that their enterprise becomes more than the sum of their gathered parts. From Dan Lautsen’s lush photography to Tamara Deverell’s sweeping sets, everything in the film begins clicking into place as Frankenstein’s experiment nears completion. And once the scientist flips the switch and Jacob Elordi begins breathing life into the stitched-together being, the film thrusts itself into a tonally richer register.

As the perspective of Frankenstein shifts to that of the creature cast out by its maker, del Toro’s concerns evolve from the cerebral to the emotional. His film offers a deep sense of identification with the larger-than-life entity in its struggles to find a foothold in human society. Elordi brings more than just his towering physical presence to the role, lending a soulfulness and solitude to the creature. His pained facial expressions and stilted physicality draw out a vulnerability, if not an outright humanity, from underneath the makeup and character design.

It’s this sorrow, and less del Toro’s vision of the perils of science without guardrails, that gives the film its beating heart, drawing a line between it and so much of the director’s other work. Del Toro stirringly showcases the creature’s agony from lacking a counterpart to help understand its existence, thus setting up a thrilling final act of confrontation with its maker.

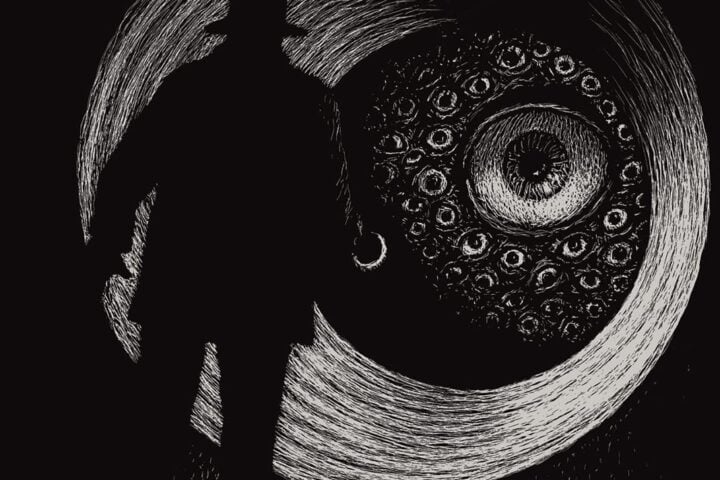

Del Toro brings an undeniable specificity to the rendering of Frankenstein and the monster, but his film resonates most profoundly on a mythic, archetypal level. Shelley, whose novel is subtitled The Modern Prometheus, didn’t shy away from such comparisons. She made direct reference to John Milton’s Paradise Lost and the Biblical story of Adam, and del Toro, trying to show us how her monster has resided inside his heart, steeps the film in Catholic imagery.

For one, when the monster here roars to life, he’s not situated atop a table, but tied to a structure that resembles a crucifix. The analogous connection makes sense for a story featuring a god-like figure who bestows his essence into a human form, then turns away from that creation in a way that sends his son into an existential crisis. A more articulate creature might have said the same words that Christ did before his death: “Father, why have you forsaken me?”

Del Toro ultimately gives his Frankenstein’s last words to a passage from Lord Byron: “And thus the heart will break, and yet brokenly live on.” In the two centuries since the novel was first published, generations of artists have used it to process the sorrow of feeling spurned by their maker or estranged from what they assumed would be the culmination of their labor. Del Toro reassembles a multitude of fragments, both lifted from the text and drawn from his own life, into a bloody and beautiful organ of empathy that will assuredly live on.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.