“I’ve been coming to New York since the 1940s,” David Cronenberg reminisced when introducing The Shrouds at the New York Film Festival last fall. “Yes,” he quipped, “that means I’m the exact same age as Joe Biden.” Unlike the 46th president, however, the pioneer of body horror is showing no signs of losing a step.

Following the longest hiatus of his half-century career, Cronenberg has emerged with a mournful and masterful one-two punch in the 2020s. Deeply influenced by the passing of his wife, both Crimes of the Future and The Shrouds find the octogenarian mulling over mortality and corporeality in fascinating new lights. These late-period films are as stomach-churning as the early genre works that earned him the nickname “Baron of Blood” while also maintaining a firm footing in the human drama that defined his later work, like A Dangerous Method.

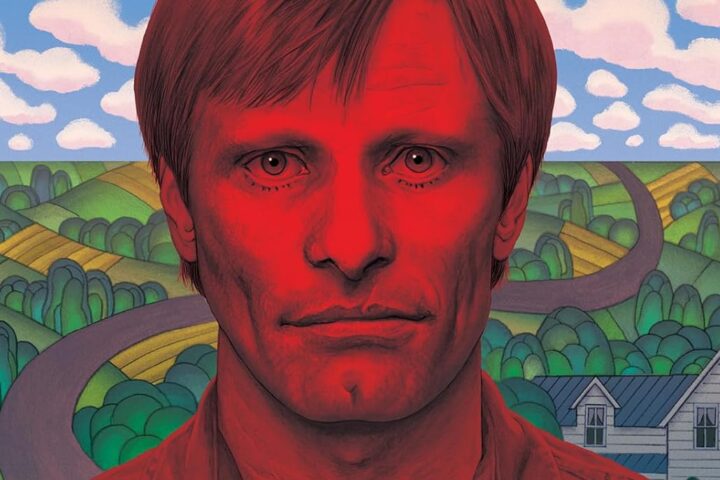

It’s not hard to see Cronenberg himself in The Shrouds, not least because Vincent Cassel’s Karsh coifs his white hair just like the director. This tech entrepreneur also believes in the power of the camera to interrogate and investigate the evolution of the body. His only slightly futuristic technology GraveTech allows the bereaved to monitor the decaying of their deceased loved ones through cameras in their coffins, complete with classic wide angles and a new high-res zoom.

But following the desecration of several graves employing his technology, including that of his late wife Becca (Diane Kruger), Karsh plunges into paranoia as he looks for the culprits. Though he has an A.I. assistant (also played by Kruger) and is haunted by the no less contemporary specter of corporate malfeasance, his emotional quest is ultimately a timeless one.

With The Shrouds, Cronenberg once again provides a probing, poignant interrogation of humans grappling with the finitude of the flesh. I caught up with the filmmaker last year when he was in town for the New York Film Festival. Our conversation covered how he conceived of the technology in the film, whether the story’s connections to present-day societal developments were intentional, and why he views the ending as optimistic.

When envisioning GraveTech, does the concept start with an idea that then gloms on to a technological interface, or are you thinking about something that already exists and what that would evoke inside of you?

Basically, you say, “I don’t want this person to be buried without me, and I want to get into the coffin with this person.” Obviously, that’s not possible. So if you’re a high-tech entrepreneur, you think of what the next best thing is. I was going through that process with my character and seeing what he would do. The answer was GraveTech. It’s letting the character run with a concept that I’ve had, but of course, it takes him to some other place than in my life.

You did research into burial traditions throughout history, but those aren’t mentioned in the film save for the Shroud of Turin that’s believed to be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ. Did that merit a mention because it’s the most famous one or because you wanted to seed the hope that beyond death lies resurrection?

No, I think Karsh makes it very clear that he’s an atheist. He doesn’t believe in a life beyond death, so his project isn’t what religion promises. It’s not about heaven or living in some kind of afterlife. The only reason the Shroud of Turin is mentioned is because it’s a shroud. It’s not a commonly used word in English, so I think most people, if you talk about shrouds, would immediately think Shroud of Turin. And the Shroud of Turin is a fake. Karsh would be competitive about that, so he says, “It’s a fake, mine are not fake.” It’s basically that.

Whenever you’re doing that research, do you find that kind of those burial traditions are more for the living or the dead?

The dead don’t hurt, like [the title of] Viggo Mortensen’s film. If you’re me, the dead have no interest in the matter. They don’t exist anymore as humans. For me, it’s always for the living.

Was the A.I. assistant Honey a part of the film from the beginning as one of the many substitutes that Karsh develops for Rebecca?

That was there right from the start, before the pandemic, I think, so it was before ChatGPT burst on the scene and had everybody talking about A.I. She’s motion capture filmically, but it fits rather well. It just anticipated, for no particular reason, everybody’s obsession with A.I.

You’ve mentioned that the technology exists to do kind of what GraveTech does in reality, even though it’s not something that in common practice. But was the point of these A.I. bots to feel both futuristic and grounded in the world of today?

Well, I think if you wanted to control an A.I. bot that you invented, it would take a little twisting and turning. There are general things you could do. Maury [Karsh’s brother-in-law, played by Guy Pearce] has created a very special kind of A.I. bot, let’s put it that way.

You deny that your art is therapy. But I was struck by the opening line of The Shrouds: “Grief is rotting your teeth.” Is there some element of making sense of the senseless by tying the emotion of grief to something so physical?

For me, that’s just obvious. Anybody who’s felt grief feels it physically, and there have been many studies about how grief really can be debilitating and shorten your life. If you’re living with constant grief, it’s the same as going from war to just normal middle-class life. It’s just a very straightforward and realistic observation, actually.

In recent years, the framework of “The Body Keeps the Score” has become a dominant way to understand how the body processes and stores trauma. I feel like your work has been there for ages, so have you felt like at all like society has caught up with the way that you’ve been expressing bodies on film?

I can’t say that my approach was unique that way. It’s possible that nobody was putting it on film so directly, maybe. But in terms of research, studies, and psychology, it’s probably been around for a long time. That doesn’t really add much to the enjoyment of the film, necessarily. It doesn’t make the film a good film, that it’s predictive of things.

You make a point that your film should always have some bit of humor and levity because life is not all horror, drama, or sadness. Was it any more difficult to incorporate your trademark humor into this film given the subject matter?

It just seems to me you can’t really live without humor. The more there is the pressure of some kind of grief or trauma, the more humor is necessary. It’s not just an escape valve; it’s a creative thing. It was no different. It was just a natural part of creating these characters.

You famously give very little direction to your actors and let them run with the script. Were you any more surprised than usual here about how they interpreted it, especially Diane Kruger playing three different characters?

No, just that I was impressed with how good she was and in such detail. To me, she really didn’t need directing. She could do it herself. I know she doesn’t feel that way, but the script gave her absolutely gave her what she needed to create those characters. That’s not always the case, and when it’s not, then additional directing from me [is needed]. But the script is the director.

I know you don’t use “body horror” to describe your work, but do you feel like The Shrouds speaks to the subtext of that genre? Our fear isn’t necessarily the changing or evolution of our bodies, but that they’ll become unshackled from our souls and just decompose without us having any say in the matter.

Because I don’t believe in the soul, I can’t really think in terms of unshackling the soul. That’s suggested in the opening scene as a matter of Jewish burial philosophy, but it’s not my philosophy or the philosophy of the main character. It’s a dream sequence. I think, for most horror films, the subject is always death and fear. Of death. Ironically, when there’s a creature from beyond the grave or a ghost, it’s a religious concept. Because if there’s a ghost or a creature from beyond the grave, then there’s a possibility of some kind of afterlife. In a weird way, however scary that might be, it’s attractive because it suggests there’s an afterlife.

Do you see a connection between humans talking to the dead and humans talking to something not or never alive, like A.I.? Is one necessarily crazier than the other?

I think it would be a very subjective, personal thing. It’s obvious that, eventually, A.I. will be able to produce a voice that sounds like your dead mate and knows enough about that person’s past, because you’ve basically fed it into that, to talk to you convincingly like a voice from beyond the grave. But I think most people who’ve lost somebody find themselves talking to that person anyway, and A.I. would just make it a little more definitively physical. You sometimes find yourself talking to your dead person, and you’re answering for them because you know what they would say. Or maybe you don’t, but you talk to them. In a way, it’s not that big of a sci-fi stretch. It’s not that spooky; it’s pretty straightforward, in some way. I’m sure that some people would find comfort in that. Others would find it very creepy. Who knows? We’ll find out.

What role do corporations play in all that? GraveTech is enriching Karsh by commodifying grief, and his rival company is promising this humanistic technology. That might sound like an oxymoron, but hearing you describe it, technology isn’t inherently alien because it derives from something human.

That’s an interesting point. The word “corporation,” what does it mean? It means “make into a body.” If you are incorporated, you make a body out of something, out of nothing, or out of an idea. Even there, the idea that a corporation is a person, there are laws that apply to it and tax obligations that it has just like any person. That was from Rome, I think, the idea of incorporation. That just sort of crystallizes what I was saying, the idea that a techno-corporation is, in a way, a strange person. It’s not an alien. Very human, created by humans for humans.

Conspiracy theories and the paranoid need for meaning-making tie into the grief storyline. But given the recent years of Covid and the mainstreaming of medical conspiracies, did that exacerbate or validate certain elements of Terry’s character?

Not at all, because it’s right from the beginning of my moviemaking. In Videodrome, there’s a conspiracy. The idea of a conspiracy as a protective, creative act that sometimes comes from unusual impulses and suggests that there’s meaning in something that’s meaningless, I had it long ago. I lived through a pandemic as a kid because everybody was terrified of polio. There was the polio shot, and yes, there were some people who felt that the polio shot would be devious and had some ulterior purpose and stuff. But believe me, we all wanted to have a polio shot because we saw what happened to our friends who got polio and were damaged for life. With the Covid go-round, I said, “Hey, give me every shot you can think of because it’s proven in my lifetime to be a valid approach to disease.”

Last night at the Q&A for the film, you declared, “The death of a loved one is impossible and meaningless.” I think the two of us might diverge on what happens to us when we die, but I didn’t find that statement pessimistic or nihilistic at all. I don’t know that I even disagree with it.

No, I agree. It’s not nihilistic or pessimistic at all. It’s a statement of fact. If you’re an existentialist and an atheist, that’s the main hurdle you have to get over to become that. I accept the fact that death is the end. It’s oblivion. It’s like what you were before you were born…which is to say, nothing. That’s the nature of our universe. That’s the nature of human life, and, in fact, all life. It’s something rather glorious, really. You might have to work hard to see it as a positive thing because the emotion of separation, and the fear of non-existence, is hard. It’s hard to imagine yourself not existing. But if you can do it, it can be quite wonderful and therefore not scary and not a negative thing at all. But it’s hard for most people to just swallow that.

Beyond just being not pessimistic or not nihilistic, do you find it actively hopeful?

Well, I said it could be glorious, and that’s what I mean. It could be a magnificent understanding and acceptance of the universe.

Do you as a person train yourself to have that muscle of hope? Your last two films in particular could be simplistically read as pessimistic because of their relationship to death, but the transformation of the body is also this glorious testament to humanity’s ability to survive and adapt.

I think the ending of The Shrouds is optimistic. It’s an acknowledgment, for example, that Karsh’s grief will never go away. Any love affair that he has will still be colored by the love for his wife, and that is something that is acceptable. It’s something that could be positive and energizing. I really see the ending of it as a positive ending, not a negative.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.