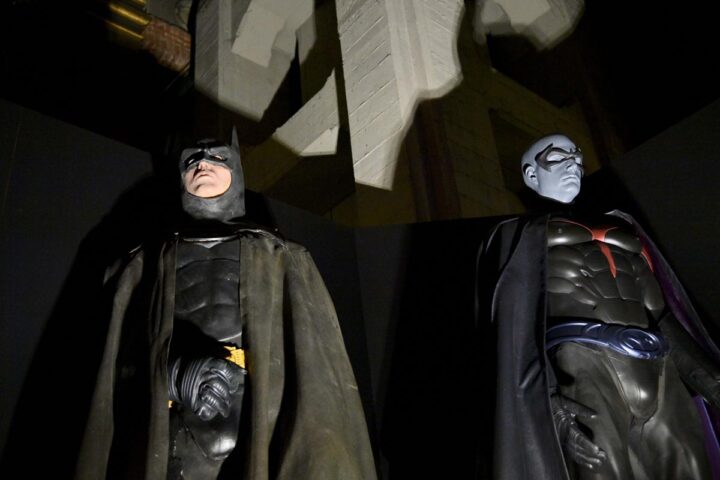

A film about fantasies slipping away, Robin Campillo’s semi-autobiographical Red Island begins with a daydream, of a world of miniature buildings and puppet-faced men facing off against a masked girl. The girl is quickly revealed to be a visualization of Fantômette, the heroine of the popular Georges Chaulet book series that bears her name, and a particular obsession of Campillo’s 10-year-old stand-in, Thomas (Charlie Vauselle).

The film unfolds largely around a military base in Madagascar, from 1970 to 1972. It’s a decade after the island country’s independence from France, but various ties to the former colonial power remain in place, with French soldiers staying on their bases and working with the local troops. Perhaps inevitably, the oddly paradoxical Red Island is at once lackadaisical and urgent, relaxed but with a clear eye for how swiftly everything will end for the characters at its center.

Not that Thomas, peering out from the army crate that he often retreats to, sees the incoming loss of his home. He’s much too fixated on the adults around him, particularly his airman father, Robert (Quim Gutierrez), and loving mother, Colette (Nadia Tereszkiewicz), as well as the burgeoning friendship with classmate and fellow Fantômette lover Suzanne (Cathy Pham).

Up until the day before the departure of the French troops, Red Island focuses mainly on quotidian matters, including Thomas’s desire for attention from his family and curiosity about the world of wayward soldiers and prized possessions around him. But through it all, Campillo and Gilles Marchand’s script feels diffuse. Its general fixation on youthful nostalgia registers as an unproductively incomplete point of view when faced with the vast questions it raises about identity and France’s place in a locale that it subjugated for over 60 years.

The narrative eventually leads to what may be seen as the film’s ultimate gambit: Red Island is told from the perspective of the white family members until its final 15 minutes, when Miangaly (Amely Rakotoarimalala), an officer’s girlfriend, has a conversation in Malagasy with a native soldier, before leaving the base and joining a celebration of the release of imprisoned protestors. This ending sends the film out on a note of optimism for a people asserting their independence, but in a way that shies away from engaging with the ambiguous nature of the central family’s final interactions: Hints of an impending divorce upon their return to France give way to an extended genderbending sequence of Thomas lurking in a Fantômette costume at night.

If Red Island is ultimately too divided in its interests to entirely function as either a grand statement on French troops in Madagascar or as a precise portrait of childhood in a strange place, it’s not without an evocativeness of its own. Trading in BPM (Beats Per Minute)’s Scope framing for Academy ratio, Campillo plays up the surreality of certain moments: the motif of skydivers in a jagged line over the hills of Madagascar, a slow-mo scene of the family’s efforts to shoo hornets out of their bathroom, and all of the amusingly exaggerated Fantômette sequences.

Most effective of all is a telling scene where military families and locals alike watch a 16mm print of Abel Gance’s Napoléon on the beach, projected onto a sheet in front of the waves. As Napoléon fights a storm while Robespierre’s radicals take control of the National Assembly, it acts as a synecdoche for another era of French rule, this one ending before our eyes.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.