Julius Avery’s Samaritan unintentionally exposes the political subtext of all superhero movies. Liberal critics may lambast its rendering of the superhero mythos as a right-wing allegory about revanchist brutality as a cure-all for urban society’s ills. Commenters could seize on the way the supervillain is intentionally characterized as a bleeding-heart do-gooder, point out that the film goes out of its way to imply high taxes are what cause evictions, and even observe the suggestive presence of an antifa-like poster on the walls of the bookstore where the fake anti-superhero-news propagator played by Martin Starr hangs out.

But what this kind of critique would overlook is that while the politics of Samaritan may be more clumsily delivered than those of, say, Christopher Nolan’s Batman movies or just about any title in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, they’re not substantially different. Most superhero movies, at base, are fantasies of male sovereignty that position charismatic men as the embodiment of social authority. Tony Stark is the military-industrial complex as funny playboy. Bruce Wayne is the police as Byronic hero. Thor is the savior as himbo.

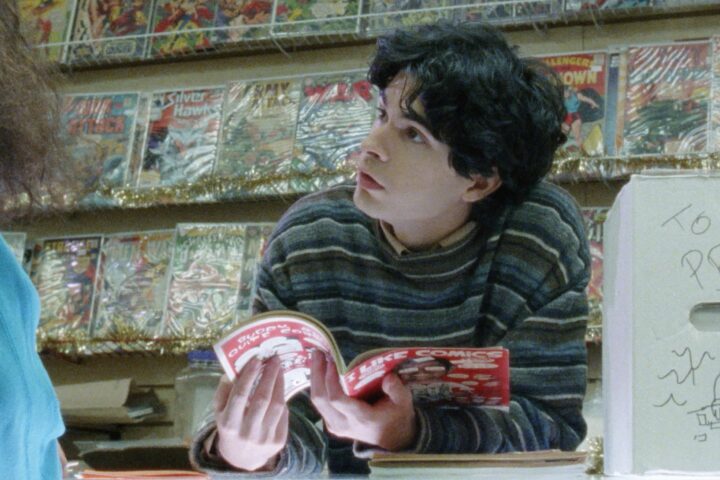

The superhero that Sylvester Stallone plays in Samaritan embodies a discredited patriarchy that needs to be made great again. This reawakening is spurred by the 13-year-old Sam Cleary (Javon Walton), a youth who’s grown up after Samaritan’s disappearance—he was rumored killed in a battle with his brother, Nemesis—and who worships the missing hero as if awaiting the second coming. However, as a wayward teen, Sam is also being courted by Cyrus (Pilou Asbæk), a local gang leader with designs on taking over the Nemesis mantle.

In the style of many a children’s movie set in “the streets,” the purview of Cyrus’s crime empire is rather vague, depicted mainly as terrorizing the people in Sam’s impoverished neighborhood. That is, until he dons Nemesis’s spray-painted hockey mask and begins hoodwinking those same denizens into following him. Cyrus tells Sam that he admires the previous Nemesis because he “only punched up,” targeting the forces of oppression. And when Cyrus appears in the supervillain’s guise, he starts spouting Bernie Sanders-like catchphrases about a people’s revolution. At this point, his villainous scheme becomes apparent, though not any more clearly motivated: to cause anarchy by promising liberation to the masses.

Luckily, Stallone’s burly bruiser is on hand to put the kibosh on prophets of freedom, false or otherwise. Going by the flagrantly generic name of Joe Smith, he lives in the building opposite that of Sam and his mother (Dascha Polanco), and Sam is convinced that Smith is the missing Samaritan even before the man survives a targeted hit-and-run perpetrated by some of Cyrus’s goons. Smith feels protective of this neighborhood kid but continually insists that he isn’t Samaritan, even as he reluctantly makes moves to stop the new Nemesis’s revolution.

Perhaps the fairest description of Stallone’s performance is that it’s only as one-note as the material, his stern tough-guy muttering and grimacing just about right for a screenplay that feels like it’s been plucked out of a dustbin left untouched since 1995. The idea of pairing a young teen with a strongman daddy figure feels like it’s been thawed out after being cryo-frozen in that post-Terminator 2 era. Beyond the film’s discomfiting politics, there’s nothing particularly egregiously faulty about its performances or plot, relative to most action-adventure quickies directed at teens. They’re simply rote and outmoded.

As for Samaritan and his nefarious leftist brother, with their metallic body suits and the sledgehammer we see wielded by Nemesis in flashbacks, they look a heck of a lot like the quintessentially ’90s superhero that Shaquille O’Neal played in Kenneth Johnson’s Steel. That Samaritan’s stereotypically sketched portrait of urban decay may as well have come out of that film speaks to the fact that there’s a fair amount of troubling racial politics at play here as well. But while Steel’s representation of disadvantaged Los Angelenos may be problematic, at least it’s hero is Black. In Avery’s film, the many people of color who appear are victims or small-time perpetrators whose potential mass agency is delegitimated by the white Nemesis’s villainy; it’s up to Stallone’s Samaritan to wield the sledgehammer.

Samaritan’s climax delivers a supposed twist that’s really a sleight of hand, reversing some roles without changing any values. What remains intact after the explosive finale is the cartoonishly Manichean worldview that the filmmakers want the audience, if not quite to take seriously, then at least to get emotionally invested in—which is close enough to the same thing. At least, though, the film’s cringeworthy combination of moral absolutism and faux social concern is enough to provoke a degree of disgust for all other superhero movies, because that, no doubt, has some utility in an age where even the phantasm of purported Marvel fatigue can’t seem to end our current cycle of insidious spectacle.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.