With The Love That Remains, Hlynur Pálmason stretches himself aesthetically and thematically in some striking ways. The Icelandic filmmaker’s fourth feature focuses on a year in the lives of Anna (Saga Garðarsdöttir), Magnús (Sverrir Gudnason), their three children (played by Pálmason’s own kids, Ída Mekkin Hlyndsdóttir, þorgils Hlynsson, and Grímur Hlynsson), and their dog Panda on their farm in rural Iceland.

Anna is a visual artist who, among other things, makes large rust-colored abstract canvases that take months to create, while Magnús (or Maggi) is a fisherman who spends months away at sea. The film begins after they have decided to break up, though if Magnús’s tendency to hang around their home whenever he’s in town is any indication, there still appear to be some romantic feelings complicating their attempts to fully tear themselves away from each other.

Pálmason, who has a background in visual art, explores these family dynamics through a vignette-like structure that sometimes feels akin to walking through an art exhibition. That’s not to say he treats his human characters as art objects, just that he puts his trust in the viewer to grasp crucial information based on the snapshots he shows them.

It’s only through one line of offhand dialogue early on—when a Swedish gallery owner says, “You’re finally single,” over the phone to Anna as they set up a visit—that we grasp that the film’s events are occurring after Anna and Magnús’s separation. And the only way we understand that the film takes place over the course of a year is through a recurring image of a knight-attired scarecrow tied to a post outdoors amid different weather landscapes.

Though many of the episodes are naturalistic in style, Pálmason occasionally indulges in aestheticizing montages and flights of surreal fancy, some more clearly motivated than others. A scene in which Anna cuts up mushrooms while making lunch for her children suddenly, and rather inexplicably, becomes a whole montage of mushrooms being ripped in half.

More defensible in context are the shots of Magnús on the ground looking up Anna’s billowing skirt, the slow motion imbuing the crude gesture with a lyricism that feels aptly attuned to the affection the man has for his ex-wife. There’s even a hilarious dream sequence in which a giant version of a rooster that Magnús has killed, to his daughter’s dismay, takes its revenge on him while he’s watching Jack Arnold’s Creature from the Black Lagoon. As jarring as some of these stylistic and tonal shifts are, they do give the film a playful feel that was much less evident amid the solemnities of Pálmason’s previous films, including Godland.

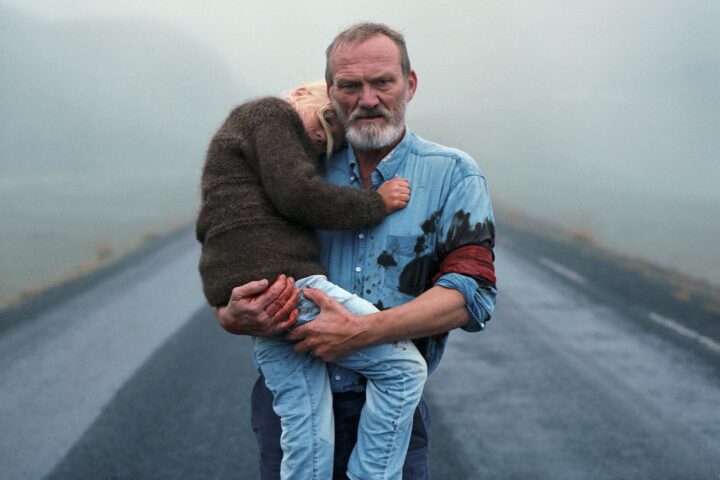

What emerges from this patchwork quilt isn’t exactly revelatory, but the film’s character details and freewheeling formal qualities make the narrative feel fresh more often than not. Anna appears to have raised her children in a very liberal environment, one that Magnús questions during the closest thing to a heated argument in an otherwise remarkably quiet and subtle film. But when one of their sons accidentally gets an arrow in his right shoulder, one may wonder if the children are all victims of parental neglect, since Anna at times appears more devoted to her art than her kids. The benefit of Pálmason’s impressionistic approach throughout The Love That Remains is that he allows us the space to form our own judgments.

The limitations of that approach, though, become apparent when Pálmason reaches for pathos in the film’s final moments, which are given over to a lengthy fantasy sequence in which Magnús confronts a living version of the aforementioned scarecrow. This is perhaps meant to visualize the man’s regret at the way his behavior has led to the fracture of his family, an impression solidified by him yelling, “Maggi the coward!,” to no one in particular while sitting alone on a tube float out at sea. But because Pálmason had kept Magnús’s inner life at arm’s length up to this point, whatever catharsis comes from this moment isn’t likely to be shared by the audience.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.