![]() Given the extreme narrative similarities it shares with Dr. Strangelove, Sidney Lumet’s 1964 thriller Fail-Safe seems destined to live in the shadow of Stanley Kubrick’s canonical black comedy. Not only do their source materials bear a great resemblance to each other—indeed, Peter George, the author of Red Alert, sued the authors of Fail-Safe for plagiarism and eventually settled out of court—but they were also released the same year. Despite both Kubrick and Lumet’s worries that the other director’s film would be detrimental to the effectiveness of their own, the two works are surprisingly complementary yin-yang partners for the way they approach their shared subject matter: an impending nuclear doomsday and the manner in which those in positions of great power handle a situation of unimaginable horror.

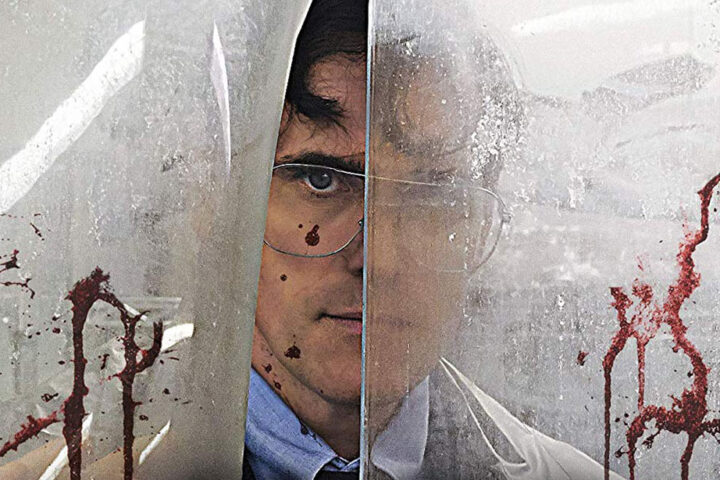

Given the extreme narrative similarities it shares with Dr. Strangelove, Sidney Lumet’s 1964 thriller Fail-Safe seems destined to live in the shadow of Stanley Kubrick’s canonical black comedy. Not only do their source materials bear a great resemblance to each other—indeed, Peter George, the author of Red Alert, sued the authors of Fail-Safe for plagiarism and eventually settled out of court—but they were also released the same year. Despite both Kubrick and Lumet’s worries that the other director’s film would be detrimental to the effectiveness of their own, the two works are surprisingly complementary yin-yang partners for the way they approach their shared subject matter: an impending nuclear doomsday and the manner in which those in positions of great power handle a situation of unimaginable horror.

Both films involve a U.S. military aircraft surreptitiously carrying nuclear weapons across the Soviet border, but while Dr. Strangelove approaches the material with cheeky abandon, Fail-Safe is relentlessly straight-laced. Aside from their disparate tones, a crucial distinction between the two films is where each one places the blame for the world being brought to the brink of annihilation. Kubrick excoriates human nature itself, particularly as it operates under the guise of leadership and global influence, suggesting that our pettiness and hunger for power will inevitably lead to our demise. Conversely, Lumet never quite grapples with the irony that those who bring us closest to destruction will likely also be the ones we need to save us. He shows a deep respect, even reverence, for those in power, locating the fatal flaw in mankind’s excessive trust in machines rather than the innately corrosive effects of power.

From the coolheaded guilelessness of the unnamed president of the United States (Henry Fonda) during telephonic negotiations with the Soviet premier to the anti-war stances of General Black (Dan O’Herlihy), Fail-Safe’s vision of political and military leaders unwavering in their dignity and compassion feels antiquated in ways that Dr. Strangelove’s never does. While some of Lumet’s portraits of powerful people veer toward idolatry, he takes great care to counter these individuals both with war-hungry Pentagon hawks—most notably the terrifying pro-nuclear military strategist Dr. Groeteschele (Walter Matthau), modeled after the notorious Cold War era reactionary Herman Kahn—and a fully integrated institutional apparatus of war that’s already too expansive and intricate to be controlled or restrained by a single man.

When the Soviet premier suggests that no one’s to blame for the mechanical failure that led to this doomsday standoff, the president replies that it’s both of their faults because they “let our machines get out of hand.” Unlike Kubrick, who portrays mankind as a very willing, even enthusiastic, participant in its annihilation, Lumet pins the blame on a removal of humanity from critical decision-making, pleading for a rollback on our overreliance on autonomous technology to make and communicate decisions being the necessary corrective.

Fail-Safe’s underlying reverence for those in power, however, does actually serve to amplify the tragedy of the events depicted in its final act, while Lumet’s moral clarity in his repudiation of nuclear armament is admirable in its forthrightness. There’s also an exacting precision in the film’s editing, its stark, minimalist compositions, and its frequent use of silence (there’s no score to be heard), which lends Fail-Safe a relentless white-knuckle tension, not only in its depiction of the military events that unfold, but in the philosophical battles that play out in rooms full of men who are quite literally shaping, or perhaps destroying, mankind.

Lumet’s depiction of that bureaucratic maneuvering carefully navigates the thin line between stockpiling nuclear weapons and being inextricably drawn into nuclear war. In doing so, he presents a discordant chorus of conflicting voices from all ideological corners during the atomic age. Despite lacking the satiric bite of Dr. Strangelove, Fail-Safe still offers a chilling reminder of how quickly poisonous rhetoric can lead to irrevocable harm.

Image/Sound

Criterion’s transfer of a new 4K restoration beautifully captures the starkness of Fail-Safe’s spare visual scheme. It’s a film full of tense, often dialogue-free close-ups, and every crease on the actors’ foreheads or bead of sweat running down their faces is rendered with a startling precision. The image contrast is also incredibly strong, with a remarkable dynamic range that displays myriad shades of grey and deep, inky black in the pools of shadows found in many of the shots. While the film has no score, the uncompressed monaural audio presents mostly clean dialogue, with only a handful of lines sounding just a tad muffled.

Extras

In this disc’s only new extra, critic and author J. Hoberman provides ample historical context for Fail-Safe, discussing the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the doomsday scenarios that gripped the public’s imagination and that the State Department planned for in the early ’60s. He stresses not only the authenticity of the film’s portrayal of heightened Cold War tensions, but also its influence on the Johnson-Goldwater presidential contest in 1964.

In his commentary track, recorded in 2000, Sidney Lumet also covers a wide range of topics, going into great detail about the political climate within which the film was released, as well as the U.S. Department of Defense’s complete lack of cooperation in helping the filmmakers attain stock footage for any of the flight scenes. He addresses the elephant in the room—Kubrick’s lawsuit to stop the production of Fail-Safe—and delves into the importance of having satirical and dramatic approaches to extremely similar source materials.

The final disc extra, a short documentary titled “Fail Safe Revisited,” doesn’t touch upon much that’s not covered in the other supplemental materials, but if you’re wondering why George Clooney loves Lumet’s film, tune into this one first. The package is rounded out with an essay by film critic Bilge Ebiri, who vibrantly writes of the effectiveness of Lumet’s humanistic realism in grounding a film about impending global catastrophe.

Overall

Criterion’s beautiful transfer and modest yet thoughtful collection of extras attest to the enduring qualities of Sidney Lumet’s doomsday thriller.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.