Sinéad O’Connor’s life and career were marked by cycles of rage and forgiveness. For the Irish singer-songwriter, the world’s ills and evils could be traced back to the Roman Empire—and the Roman Catholic Church in particular. Her beef with the Church didn’t repel her from religion, but propelled her into a perpetual search for meaning amid what she viewed as corruption, abuse, and injustice.

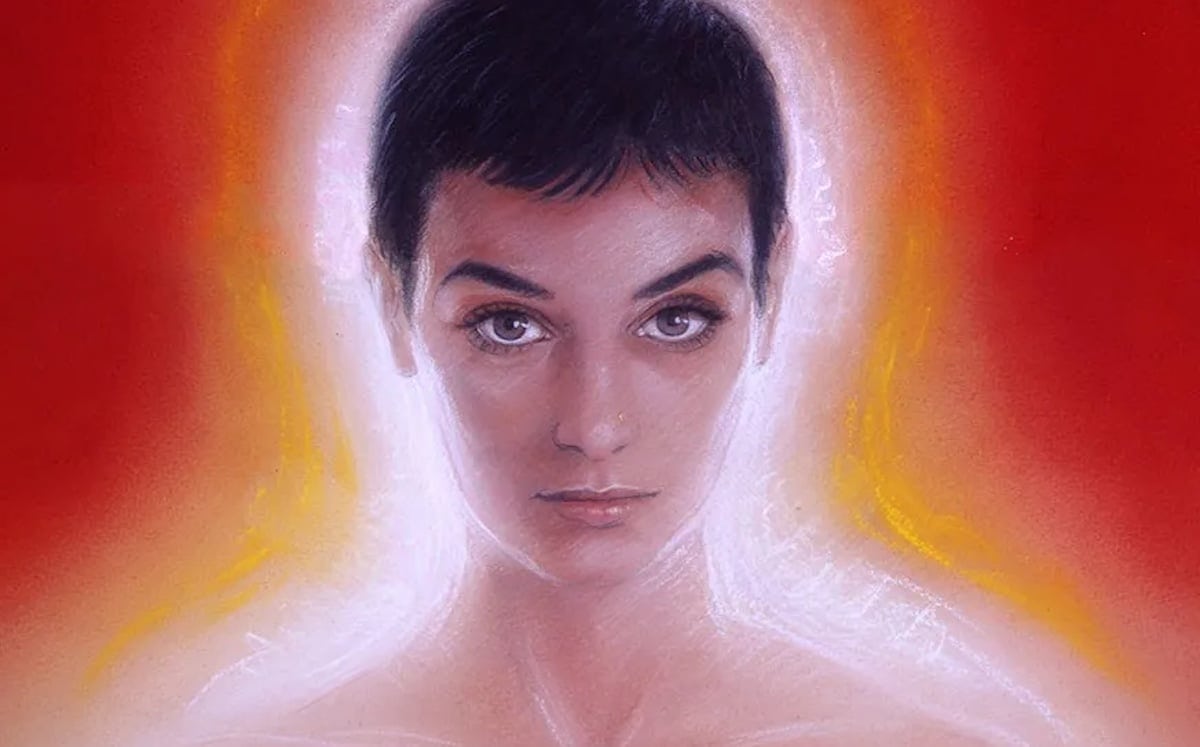

O’Connor’s fiery debut album, 1987’s The Lion and the Cobra, is rife with allegorical stories about war, ghosts, and slain dragons, signaling from the very start that she wasn’t just an artist, but a warrior. Her quest for justice and salvation deepened and matured over the years, reflected in her 1997 EP Gospel Oak, 2000’s Faith and Courage, and 2007’s ambitious Theology.

With her shaved head and steely persona, O’Connor was the unlikeliest of pop icons, but she inadvertently attained stardom when her cover of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” topped the charts around the world in 1990. Two years later, that fierce personality infamously got O’Connor into trouble when she appeared on Saturday Night Live and tore up a photo of Pope John Paul in protest of the papacy’s complicity in sexual abuse within the Church.

O’Connor became a frequent target of the media and, in the ensuing years, publicly struggled with mental health and the loss of her son. Through it all, she pursued grace through her work, to which she returned again and again despite repeated threats of quitting. Even just weeks before her death at 56, she revealed that she was working on a new album and planning a tour.

The 20 songs below represent not just a cross-section of O’Connor’s impressive discography, but a glimpse into the mind and spirit of the artist, the iconoclast, and the woman herself. Sal Cinquemani

Editor’s Note: Listen to our Sinéad O’Connor playlist on Spotify.

20. “This Is to Mother You”

The standout from O’Connor’s Gospel Oak, “This Is to Mother You” initially scans as another delicate hymn to the singer’s children, like 1994’s “My Darling Child,” until it gradually reveals that the object of its doting is actually a lover. The surface serenity of the song likewise is disturbed by allusions to “violence” and “mistakes,” which reframe its affirmations as something thornier—an assertion of agency in a relationship, or an implicit acknowledgment of the unfair hardship many women endure in order to nurture damaged men. All that depth is wrapped in a featherweight lullaby. Sam C. Mac

19. “All Apologies”

Stripping down “All Apologies” even more than Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged version, O’Connor whispers Kurt Cobain’s lyrics over spare acoustic guitar to accomplish what so many of her best performances always did: She homes in on the song’s lyrics. When Cobain was alive, he referred to “All Apologies” as a song of “peaceful, happy comfort.” O’Connor’s crystalline delivery makes you notice anew lines like “Everything is my fault/I’ll take all the blame,” tapping into the hurt, grief, and shame at the song’s dark core—and notching another classic, unconventionally interpreted cover in the process. Mac

18. “Hold Back the Night”

Produced by Eurythmics’s David A. Stewart, “Hold Back the Night,” a standout track from Faith and Courage, has rightfully earned its place as a fan favorite over the years. The love song-cum-spiritual hymn finds O’Connor delivering one of her most plainly naked vocal performances in an achingly direct plea for salvation, employing apocalyptic imagery—“Everything’s burned/Everything’s gone”—as a metaphor for the dissolution of a relationship. Cinquemani

17. “Black Boys on Mopeds”

The implicit parallel drawn between the 1983 police killing of Colin Roach and the massacre of student protestors in Tiananmen Square a few years later in “Black Boys on Mopeds” may be a touch inelegant, but O’Connor’s broader message of decrying the hypocrisy of Western leaders commenting on global atrocities has only become more relevant. Same goes for her prescription of systemic racism, and for an eerie prediction of her own precipitous fall from grace: “These are dangerous days/To say what you feel is to dig your own grave.” Making sense of O’Connor’s career requires grappling with the extent of her own personal failings, but as “Black Boys on Mopeds” reminds us, it should also necessitate another look at how society buries its own inconvenient truths. Mac

16. “Success Has Made a Failure of Our Home”

Ever the maverick, O’Connor followed up the successful I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got with a collection of jazz and pop standards. The album’s title, Am I Not Your Girl?, was lifted from the lead single, a cover of Loretta Lynn’s “Success,” a pointed selection given O’Connor’s rejection of the fame she’d recently amassed. She and producer Phil Ramone brilliantly transform Lynn’s lilting Nashville hit into a big-band torch song, punctuated by lush orchestral swells and blaring brass. By track’s end, O’Connor repeats the album’s title ad nauseam for a minute and a half while the horns reach a frenzied pitch, imbuing the song with a self-lacerating paranoia that eludes the original. Cinquemani

15. “Mandinka”

The opening moments of “Mandinka” are as stadium-ready as O’Connor’s music ever was. That the song soon transitions into more slippery indie-rock territory, with an octave-jumping vocal that recalls nothing so much as Elizabeth Fraser of Cocteau Twins, is more in line with its abstract and questionable message. Regardless, the song remains the perfect wooly calling card for O’Connor’s heaviest album, The Lion and the Cobra, and a powerful showcase for what was (for a time) one of the most elastic voices in pop, modulating with unrivaled facility between gentle coos, caterwauling screams, and guttural growls. Mac

14. “The Healing Room”

A prefab assemblage of new age-y aphorisms (“I have a universe inside me”), buzzing radio static, giggling children, and time-stamped dub and trip-hop signifiers, “The Healing Room” is the great Sinead O’Connor litmus test: the gateway to her most sonically eclectic (and longest) collection of original songs, Faith and Courage. Its five-and-a-half minutes thrum and pulsate, establish zen-like equanimity, and tie together linguistic nursery-rhyme knots. It’s also at least a little bit in on its own joke, as levity was always a rare commodity in O’Connor’s music, as was accommodation. Her “healing room” never seems like a closed-off personal space, but a communal one, a state of mind that anyone can achieve. Which might scan as trite were it not coming from an artist who never came by her contentment easily. Mac

13. “You Made Me the Thief of Your Heart”

Co-penned by Bono, this track from the soundtrack to Jim Sheridan’s 1994 film In the Name of the Father positively oozes drama and pathos. That’s thanks in large part, of course, to O’Connor’s theatrical performance and producer Tim Simenon’s epic soundscape, awash in portentous keyboards, propulsive drum programming, and Celtic fiddle that, together, gin up an almost primal sense of tension. Cinquemani

12. “Drink Before the War”

In her memoir, Rememberings, O’Connor stated that “Drink Before the War” was inspired by the headmaster at her boarding school, but the more popular interpretation is that it’s a metaphor for Irish independence from the U.K. Ultimately, it’s a song of limitless application, as O’Connor’s narrator gives voice to anyone who refuses to be subjugated by a would-be oppressor. O’Connor knows full well that those oppressors are a class who fancy themselves “good men” whose “parents paid [them] through” and who cannot see past their own privileges to know that their pride will be their undoing. It’s a message as timely today as it was in 1987, and it’s a reminder that O’Connor was always telling the truth. Jonathan Keefe

11. “I Want Your (Hands on Me)”

In terms of production, “I Want You (Hands on Me)” is one of the most conventional pop song of O’Connor’s career. That it didn’t gain any real traction on U.S. radio is certainly a testament to the song’s sustained provocations. The repetition of the “put ‘em on me” hook leaves no doubt whatsoever as to what O’Connor is up for, and she moans “I wanna move, will you/I really wanna feel you” with a candor that would surely have horrified the Moral Majority. Fittingly, the song was used to soundtrack a gnarly death sequence from A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master, placing it into the context of the slasher genre, where sex and violence are inextricably linked. Keefe

10. “The Wolf Is Getting Married”

Few other singer-songwriters have such a profound connection to the primal, and one of the overarching themes in O’Connor’s work is that a feral sense of rage is held in check, barely, by explorations of faith. She knows she’s a wolf, which is why “The Wolf Is Getting Married” is a song on which she sounds surprised by the sudden onset of romance. “Your laugh makes me laugh,” she sings, and her tone is one of pure gratitude and wonder. “Your joy brings me joy” is perhaps the simplest and loveliest expression of hope in O’Connor’s entire catalog, and she sings that line like she’s trying to convince herself that just maybe she deserves that joy. Keefe

9. “I Am Stretched on Your Grave”

The audacity of “I Am Stretched on Your Grave” is in O’Connor’s choice to set a ballad of grief-driven madness over a hip-hop beat. But it’s precisely her contradictions and rejections of pop norms that make her music so vital. O’Connor’s is an alien logic, which makes it impossible to anticipate the choices she makes as an interpreter. She doesn’t cover songs so much as she possesses them, and on this song the extremity of the narrator’s desperation is matched by the intensity of O’Connor’s performance, as though she could resurrect the dead through the sheer power of her voice. Keefe

8. “Fire on Babylon”

With her newly honed bel canto vocal, O’Connor attacks the operatic scales of “Fire on Babylon,” mustering a religious-like conviction, while producer and ex-husband John Reynolds whips up a heady mix of reggae, trip-hop, squelching funk, and—why not?—a Miles Davis sample. It’s one of the most galvanizing songs in O’Connor’s catalog, one of the few that marries her appetite for outspoken protest music with something that sounds like a proper radio single. The lyrics are as much an indictment of O’Connor’s treatment by her mother as they are a radical cry to torch the systems of oppression she faced off against her whole life. Mac

7. “Three Babies”

In her memoir, O’Connor describes “Three Babies” as a “prophecy,” and what she was able to intuit about the future remains one of the most compelling through lines in her career. Both as a meditation on miscarriage—on the maternal instinct that the children she lost will still always be “in my blood and my bones”—and as a vision of what she believes will be her future failings as a mother, “Three Babies” captures a peculiar iteration of grief that not everyone experiences or can understand. Still, the intimacy and vulnerability of O’Connor’s performance demand empathy. Keefe

6. “Just Like U Said It Would B”

While many tributes in the wake of O’Connor’s death have focused on almost everything about her but her artistry, there’s no way to separate her public persona from a discussion of how she was as right as she was righteous. “Just Like U Said It Would B” is a song in which a modern-day Cassandra rages against a fate that she can foretell. She asks questions that she already knows the answers to—“When I walk off the stage…will you stay?”—and she knows that her anger at those answers is entirely earned. “Cancel Culture” wasn’t in the lexicon in 1987, but O’Connor knew what was coming all along. Keefe

5. “Feel So Different”

Like Björk’s “Hunter,” “Feel So Different” is more fugue than pop song. For nearly seven minutes, a stately string orchestra traces O’Connor’s evolving emotional state, which moves past post-breakup malaise into a full-fledged spiritual metamorphosis. “I should have hatred for you/But I do not have any,” she sings at around the four-minute mark. Then the arrangement turns bright, and she jumps up into a piercing falsetto to deliver the most cathartically intense, if grammatically dubious, lyric: “All I need was inside me.” Coming off a debut album full of primal-sounding indie-rock songs about holy wars, “Feel So Different” was a balm, and in the chaotic intervening years, its grace and measured poise feel all the more moving. Mac

4. “No Man’s Woman”

At first a seemingly boilerplate feminist treatise, the lead single from Faith and Courage is less a takedown of the patriarchy than a tribute to O’Connor’s spiritual independence. “No Man’s Woman” is one of the artist’s most commercial singles, all crisp beats and guitars propelled by a deceptively catchy hook that’s almost as unexpected as O’Connor’s piety. Cinquemani

3. “Nothing Compares 2 U”

Nothing compares to this song, in which pop music’s most emotion-rich voice sings words by pop music’s most emotion-rich lyricist. Similar such meetings of titans have resulted in disasters before, solipsistic earsores mostly, but O’Connor—like she would do some time later with Nirvana’s “All Apologies”—doesn’t treat “Nothing Compares 2 U” as if it were a cover. She performs Prince’s lyrics as if the emotions inscribed in them were her own, and the proof is in her hauntingly aching belting. The experience is, like that tear that streaks O’Connor’s face in the song’s video (a response, the singer has claimed, to the line “All the flowers that you planted, Mama/In the back yard/All died when you went away”), practically holy. Ed Gonzalez

2. “The Last Day of Our Acquaintance”

Throughout I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, the trials and tribulations of O’Connor’s relationships are linked directly to her career. Her breakup with her husband, John Reynolds, is likened to a business transaction on the stunning “The Last Day of Our Acquaintance.” Anger, relief, and despondency are simultaneously bundled up in O’Connor’s voice. She begins delicately, mournfully—“I know you don’t love me anymore/You used to hold my hand when the plane took off”—and gradually builds until it erupts with the ferociousness of a woman scorned. Cinquemani

1. “Troy”

All of the different tensions in O’Connor’s career are pulled piano-wire taut on “Troy.” She vacillates between open-hearted sincerity and outright rage within the same thought: “I’d kill a dragon for you” is simultaneously a paean to devotion and a threat, and it’s something that would sound absurd coming from almost any other artist. And while she self-flagellates for the intensity of her love for someone who ultimately betrayed her, her final, repeated refrain—“You’re still a liar”—remains one of the most damning rebukes in all of pop music. At once a beautiful composition and arrangement, “Troy” is punctured by O’Connor’s fierce, atonal yelps. It’s a performance that makes it clear that she’s eager to destroy the beauty of her own instrument and would never be bound by conventions of how popular artists can or should sing. Keefe

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.