In writer-director Charles Williams’s Inside, Cosmo Jarvis delivers a flinty performance as Mark Shephard, a prison inmate who becomes a father figure of sorts to his new cellmate, Mel Blight (Vincent Miller). Mark is notorious inmate who, imprisoned for the rape and murder of a child, found religion behind bars and now sermonizes at the prison church about miracles. Spellbound by his cellmate, the teenaged Mel plays the organ, feeling a sense of purpose, if not the spirit, that Mark speaks so rapturously about.

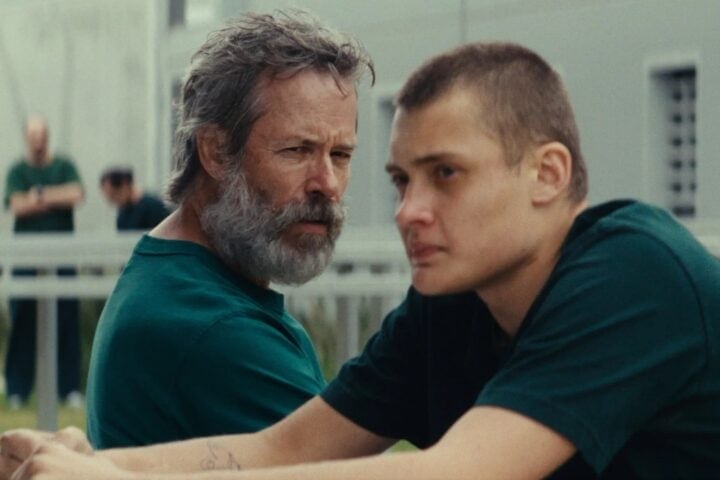

Williams’s prison drama is at once a nervy thriller and intense character study. Also at the center of the film is Warren Murfett (Guy Pearce), who, after Mel becomes his new cellmate, orchestrates a plan to erase his gambling debts if he can get the teenager to kill Mark, who has a sizable bounty on his head. As each man processes their thoughts about sin and redemption, guilt and forgiveness—sometimes through letters they write to their victims—Inside becomes a fascinating examination of how people can (or won’t) change. Mark, Mel, and Warren all seem resigned, and that desperation informs the actors’ lived-in performances.

Jarvis’s performance is alive with electrifying affectations, from a gravelly voice to facial expressions that sometimes cause his mouth to become rictus-like. The actor is especially mesmerizing whenever Mark preaches, bringing a simultaneously tender and menacing charge to his scenes with Miller, as in one where Mark baptizes Mel. Jarvis makes you see in ways expected and not, as in the way Mark discusses a St. Christophe medal, that his character is beyond repair, and how the cross he has to bear makes him so dangerous.

Ahead Inside’s North American premiere at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival, I spoke to Jarvis about what drew him to the role of Mark, how he built the character, and his thoughts on the character’s ostensible path toward redemption.

Do you lean toward dangerous roles? What appealed to you about playing Mark?

First and foremost, it was Charles Williams’s script, because it had a kind of symmetry in the relationships between the three principal characters. That symmetry solidified the shape of the narrative, which felt very complete. In terms of Mark, I guess, it’s a credit to Charles’s writing that the story is concerned with oddly something more fundamental than the truth about [Mark’s] character. It went deeper than those things. The circumstantial positions of all of the characters were secondary to what was at the film’s heart, yet also intrinsic to what the story was trying to root out and get to. I’d never played anyone like Mark before, and I found his demographic interesting—where he came from, and what he was trying to be. All those complexities made for a welcome challenge.

There is a pain Mark’s voice, and he has a very taut body language. But we also see his humanity. He shifts from menacing, to mesmerizing, to vulnerable sometimes within the same scene. He’s perpetrator, absolver, and a victim. How did you find his character? He’s a monster and a seducer. Does he have a conscience?

I think you have touched on the narrative function of Mark as a character. In his case, there’s no binary answer. He’s struggling to arrive at a conclusion about himself and his past and what he might be in the future. That’s why he is the way he is. Because he’s on an [uncertain] voyage seeking some kind of redemption or a mechanism by which redemption may occur.

Do you think Mark can be redeemed?

I don’t think that is for me to say. I think that’s too big of a question because it infers a potentially objective truth. I think he’s asking himself that question daily.

Through your performance you sense Mark’s internal conflict. He wants to be good, but he can’t be good…

It’s the one thing [Mark] must do, but there’s no point in him doing it because he is this. He thinks, “What’s the point of getting better?” Because he will never be better because of what he’s done. He goes through that and whatever conclusion the film has to offer is out of his hands.

There’s a line about Australians not being comfortable in their own skin. Do you think Mark is? He carries himself a certain way in his cell, but he’s different when giving his sermons, motivating people. He also has a very specific wound.

I think when he’s in the throes of his persona of a righteous leader who’s offering guidance and who’s doing something that to him feels so profound that it supersedes any other feeling, the rush of doing that keeps him in a place of feeling like living is tolerable. It’s the act of self-delusion, but not conscious self-delusion. When he embraces this persona of the guy on stage—philosophically, spiritually, morally—everything seems to be okay.

Mark has found religion and tries to motivate the other inmates with his sermons. Does he believe what he preaches? I wasn’t sure. Is he doing this, not as an act, but because he feels this is the way to redemption? Or if he says these things often enough, he will believe them? Or is he doing it to bond with the other prisoners?

I think he’s doing it because he believes it, but he believes it through the conscience of somebody who’s susceptible to making something rigid malleable. And by that I’m referring to the doctrine of that particular faith. I don’t know if there are any objective arbiters of spiritual guidance.

He’s trapped in this cell, and this preaching is his escape. That’s his therapy. His speeches are about sin and forgiveness, pain and guilt and shame. What are your thoughts on how he processes those feelings?

I didn’t approach him with a mind to conclude an absolute understanding of his stance on anything. I felt that was impossible to do with such a character. I had to approach him minute to minute, hour to hour. Those concerns he had at that time were his only concerns, and he would be concerned about them fully, and be sincere about them fully, but I don’t think any of them would inform a forthcoming one in a meaningful, permanent way. He’s a very impermanent character. Because he’s a man trapped between where he came from and where he wants to be.

Part of that is his mindset in prison. How did you get into the prison “mindset?” What did you learn about being in prison or studying inmates?

We shot the movie in a prison, and that certainly gave you an understanding of incarceration, particularly in such a modern facility. It’s a modern purpose-built final structure designed to keep people inside of it. It wasn’t a fundamental contributor to how the character was prepared. I wasn’t tasked with playing someone who was avidly trying to escape prison or had a hope at parole. I was playing someone whose circumstance required an almost historical acceptance of the facts of his circumstance, which, in a way, made them undebatable. In Mark’s case, what’s left is only the issue of spiritual, moral, and psychological redemption and change.

What observations do you have about Mark’s relationship with Mel? I like how Mark sizes Mel up. What does Mark see in this young man? Why does he treat him the way he does? That was interesting—he doesn’t have to be kind to him—but befriending Mel makes Mark vulnerable.

I don’t think that was his plan. If Mark considered himself as someone who potentially might make amends or undergo redemption through attempting to help others, I think that the arrival of someone like Mel—Mel’s age and situation—was an almost welcome confirmation for him to become that person for this young man.

Which is Warren’s role. Mark could be this mentor, but Warren is asked to do that. We see Mark struggling, and trying to understand what he should do, and Mel gives him an opportunity to help him.

Warren has foresight and plans, but Mark doesn’t have these kinds of agendas. He’s like a mast and a sail that isn’t attached to any vessel. Whenever Mark is doing anything, he’s doing it in the moment. His past is soiled, and his future is condemned, so what’s left are those minute-by-minute actions. The very fabric of Mark’s spiritual connection is tested, if not destroyed, by what unfolds through Mel. Someone of Mark’s beliefs would link everything to a destiny of some sort, to a higher power, and if everything that happens is happening because of your relationship to a higher power, when challenging and bad things happens, that’s why they say, “faith is tested.”

Then there’s the tense exchange between Warren and Mark…

It’s one of the film’s most claustrophobic scenes. I thought that it was quite ambiguous. There were almost no contrivances for the dramatic weight despite the circumstantial significance of these two characters meeting each other and having an exchange for the first time.

Can you comment on the ambiguous morality of the film?

[To me], Mel represents the sanctity of youth, and the idea that it’s important that younger people aren’t led astray and that it’s difficult to stay on the right path.

Why do you think Mark strayed? You’re playing it as a form of grief that has an element of regret.

His backstory was written for me. I think a lot of his opinions on what happened and why can be garnered from his present actions in the narrative that we see and a lot of that informed in a way what he came from and the distances he’s willing to go to condemn himself and try to be someone better. It’s not for me to judge.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.