A quarter of the way through the 21st century, filmmaker Jia Zhang-ke has emerged as the foremost cinematic chronicler of contemporary China. His latest film, Caught by the Tides, ought to silence any doubts to the contrary. In a miraculous medley spanning over two decades of his country’s history, Jia excavates hidden stories within his past filmography while simultaneously casting his glance toward the future.

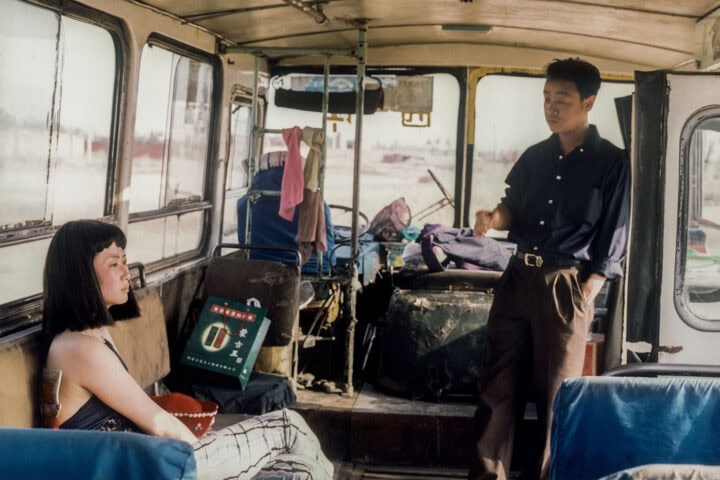

While it’s not necessary to know the background on the origins of Caught by the Tides to understand it, the context of its creation can only help enrich the experience. Like many during the pandemic, Jia looked inward at his own material as the outside world remained closed. Among footage used and unseen from his films like Unknown Pleasures, Still Life, and Ash Is Purest White, a larger story began to emerge on both a micro and macro scale. Once lockdowns lifted, he shot contemporary footage to round out this unconventional triptych about a woman, Qiaoqiao (Zhao Tao), searching for her lost love, Bin (Li Zhubin).

To watch Caught by the Tides is to witness a master filmmaker submitting to the vagaries of personal and historical memory. As he pinpoints the spiritual connections within his archive of images and sounds, Jia finds a new way to navigate time through sensation. The product fuses documentary, drama, and remix into something unique and unparalleled.

I recently caught up with Jia in New York ahead of the IFC Center’s retrospective of his work. Our conversation covered how he developed the new cinematic language necessary to bring his vision to life in the edit, what interests him about technologies like TikTok or A.I., and why he thinks the shifting nature of society has fundamentally shifted our conception of time.

This is your third consecutive narrative feature that takes place across three time periods, not to mention your third film with the character of Qiaoqiao. What interests you about such spans in the period of time?

I really [wanted to] examine the individual characters, their challenges, and their changes. I do think the previous films mostly were about a particular time and place, the slice of life that I was trying to capture. In order to recapture the essence of the challenges and changes, I need to somehow pinpoint certain important and significant junctures in the old phases of their lives and use that as a way to structure the film. The reason I was drawn to this type of longtime span for the past three films, starting in 2015 especially, is because of how life has been so fragmented now. It’s almost like a reaction to how fragmentedly we experience our lives now. I’m trying to find a new system or way to really present the new way of living now. Also, we can observe how we live with this type of historical perspective by using the triptych structure.

In Caught by the Tides, we can see so many things changing across two decades: the country of China, the fashion, the filmmaking tools, and technology. Do you think people have also changed as much?

Indeed, I do think that in terms of the impacts on individuals, you can see Qiaoqiao as the embodiment of the changes that individuals have gone through during these past 20-plus years. I do think that, in the beginning of the reforms starting in the 1970s until now, you really see how this concept of how to be a modern person as an individual is also part of that modernization movement, even though the evolution of people in general is a slower process. But it’s just as important and significant a process of modernization.

For this particular character, you see that she was very much trapped in this predicament in terms of her romantic relationship. [Early in the film], she was very tormented by that, and later on you see that she has evolved as a character and is now an independent, thinking human being, making her own choice. That’s the kind of transformation I’m trying to capture with what happened with the entire population in China: the awakening of independent identities and ways of thinking—and, also, this idea of female consciousness.

You’ve talked about needing to employ a new cinematic language to fit the changing times in this film. How did that emerge? Did it arise organically from revisiting the old footage during the pandemic?

During the process of making this film, which was during Covid, the search for the new language happened in the editing room. Through that process, I had to constantly subvert myself and really turn things upside down to rethink how I was going to tell the story and find a new language. The conventional way of storytelling and film language wouldn’t be sufficient to tell [a story that spans across] twentysomething years, nor to tease out the kind of complexity of emotions that I wanted to capture in this particular film.

I thought that in order for me to use this pair of protagonists as a starting point, then simultaneously present the complexity of the social changes in the background, I joked that I needed to rely on something more like quantum physics than on a clear, linear, causal structure to build the story and narrative. [I was] trying to find the hidden connections among things that are seemingly unconnected. That was the starting point of subverting my practice and trying to find a new way of finding those hidden connections among, in this case, the footage that I had. The new film language is very much about a new way to feel through films, and I think that you can only find it during the process of either editing or in the production of filming something.

Switching gears to the most contemporary element in the film: TikTok. Do you think of it as just another tool for capturing the world, like the digital video technology was in the early sections of the film?

I do think that, as filmmakers, it’s inevitable that you need to deal with the evolutions and the introduction of new media. For me, TikTok is just one of the many examples of how certain platforms will change how people communicate. What I’m trying to figure out isn’t only how people communicate differently, but also what’s behind the new way of communication, the economic models, the principles, and the modes of operation for that particular new media.

Is that same spirit behind your curiosity about A.I. technology?

For A.I., I’m definitely very much interested in how it generates images. That has everything to do with what I do as a filmmaker. For any type of new technology or media, my position is always that I’m not going to have any kind of preconceived notion or judgment about it until I actually get to know it and use it. Then, I will have a better understanding of how I’m going to react to it. I just recently made a short film, about six minutes, about artificial intelligence made exclusively using A.I. My reaction right after I had made this particular film is that I prefer to actually use the camera in real space to make a film. But the progress of this particular technology is really, really fast and something that we need to understand more as it evolves. This might mature in the very near future, but at the same time, I’m very clear on the fact that I still prefer to use the camera to deal with real spaces on location.

Your films, in particular Caught by the Tides, show the limited control that people have over destiny and time. But the essence of filmmaking is a human exerting control over time. Is that a tension you grappled with in the making of this film?

I think that’s exactly why filmmaking is so charming and so attractive to me. Fictional devices are an important vehicle to understand the reality that we live in. For me as a filmmaker, to be able to create this type of fictional world, it’s almost as if I’m playing a god that has full control of what kind of fictional world I want to create in order to tease out the stories and the realities that I want to depict in my film. So, on that level, yes indeed.

I was so struck by a line in Xiao Wu, which I saw at your IFC Center retrospective: “If the old doesn’t go, the new won’t come.” Since the world currently has an appetite for the demolition of the old, is there anything you think people can learn from the Chinese experience of the modernization project?

I do think that the one thing that’s constant in the world is the changes that we experience in our lives. Change comes in many different forms, including the destruction of city spaces, human connections, human relationships, and human emotions. To survive this type of constant change, human beings need to somehow go through the process of rebirth, almost like the phoenix rises from the ruins—to then be able to find a way to forge ahead and live on. It comes with the territory; the process of change will involve destruction. Through those destructions, we will have the process of rebirth. That’s something that you see, not only in terms of city landscapes, but also in human relationships or individuals in general.

I think that’s an interesting topic to discuss for a lot of Chinese people. Growing up, you were conditioned to think about the concept of time in a traditional way. The overwhelming description of that tends to use this circular way of thinking about time. If the flowers wither, they will bloom again next season. But I think a lot of people, especially in the past twentysomething years, are experiencing time more in a linear way. If something disappears, you can never get it back the exact same way that you experienced before. I do think that there’s this inconsistency between what’s been taught and how people experience time.

But I do think that, on some level, this concept of destruction and rebirth can actually be interpreted as a combination of the circular and the linear. When you think about a line [drawn] in a circular way, it’s the longest line that you can have. There’s no beginning, there’s no end. That encompasses the idea of the combinations of linear and circular time.

Translation by Vincent Cheng

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.