Few working filmmakers today combine rigor and playfulness in their approach to their art, and with such aplomb, as Miguel Gomes. Over the past two decades, the Portuguese director has enchanted both festival circuit and arthouse crowds with his inventive approaches to deconstructing cinema’s unique relationship with artifice and time.

Grand Tour finds Gomes at his most approachable yet inscrutable. The genesis of the film, which won him the best director prize at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, began with a small anecdote inside The Gentleman in the Parlour by Somerset Maugham, in which an English man runs away from his fiancée across Asia in the early 20th century. Gomes expands these two pages into a two-hour feature split across two distinct halves. The first follows the fleeing Edward (Gonçalo Waddington) as he hops across the continent in cowardice, while the second details his jilted lover Molly (Crista Alfaiate) in hot pursuit.

But that’s about the only neat division Grand Tour possesses. Interspersed within these studio-shot fictions are documentary footage that Gomes compiled in contemporary times from each Asian country that Edward and Molly visit. In contrast to historical films where interstitial sequences are frequently outsourced to archival material, these present-day scenes challenge the viewer’s temporal orientation. Gomes makes the setting and its post-colonial beauty, not his invented characters, feel more proximate in a way that requires an audience to participate in the constant and invigorating calibration of their relationship to the film.

I spoke with Gomes ahead of Grand Tour’s American release. Between sips of red wine in his office in Portugal, he described how he developed the film’s central artistic dialectic, why puppets became such a central motif, and what he’s learned about his own work from how audiences create meaning within it.

Why were you so intent on going on the same journey as the characters before writing Grand Tour? What did you gain by going before them?

I didn’t want to write these sequences in the studio, shot with the actors [playing] characters, without first doing the trip, recording some images, and doing the exercise of thinking, “Okay, this sequence of Molly doing this and Edward doing this will appear just before this cockfight in the Philippines and after these monks in Japan with these baskets on their head.” It provided me a reality that would limit the range of the fiction, which isn’t bad for me. It’s good, because I had to react and not just have a blank page where everything would be possible.

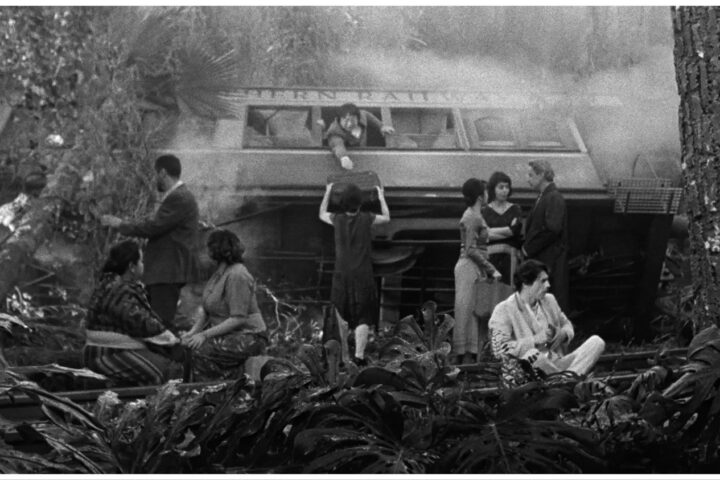

[Josef von] Sternberg was doing these amazing films about a completely fake Asia shot in Hollywood studios with Marlene Dietrich, and these are important films for me. I think they’re beautiful. During the time I was making the film—I started to shoot in 2020 and ended in 2024—it wasn’t possible to do this the way he was doing it. But I wanted to work with this kind of image, this imaginary, fake Asia that Hollywood and cinema built but to give it a different context. I thought about this ping-ponging dialectic between what the present can give the past, a past that came from cinema, and what this fiction made by cinema about love stories in Asia can also give to the present-day images we shot in Asia. I said, “Okay, let’s do the ping pong. Let’s do these two very different shootings, put them together, try to have transitions between one thing and the other, and see what kind of the film it will give in the end.”

When making these more forceful ruptures in the film’s construction, such as a hand anachronistically reaching for a cellphone or words being bleeped out, how are you gauging how far you can push these interventions?

It really depends. This is like making a pact with the audience, knowing some basic things. One of them is quite basic but sometimes neglected: The audience is composed of different people, so I know when I do a thing like this, I can have some of them saying, “What kind of stupidity are we seeing? The guy doesn’t know there were no cellphones in 1918, is the director [an idiot]?” I can get this kind of reaction, and I can live with it, to be honest. But you can also expand the range of the film with these anachronisms because cinema has this ability, but it depends really on the acceptance of the viewer and how [they allow themselves] to be a little bit more innocent than we’re used to being today regarding our relationship with cinema.

Now, it’s quite different from the past when I think people were more available with respect to fiction to believe in the unbelievable and just assume, “Okay, I’m not seeing reality, but I’m seeing something that’s connecting me with life.” Life and cinema are composed differently, and in this film, we try to create a single time composed of things of today and things from the past, with a very artificial recreation of Asia in a studio. Then, it’s a little bit up to the viewer to glue all of this [together]. There will be people who will not do it at all. They don’t even know they can do it. There will be some people who will do it, and when they do it, it’s beyond my control. Sometimes, they can over-interpret things, but I think it’s useful to bring today’s world into the past and to contaminate the landscape of today. What’s happening in the story with the characters will transform what you’re seeing. These are things that interest me in cinema.

How do you conceive of the voiceover in your films? In many ways, it feels like a more truthful experience of the events than what we see. Sound enhances and sometimes even contradicts the image of Grand Tour.

If it was just saying the same thing you see in the images, it would be useless. You’re already seeing it. What I feel interested in is the experience of the viewer who, sometimes, is just following what’s happening [when] the characters [are] on screen. You see them doing things, you’re in the same zone and space [as them], and then you have the voiceover projecting into the viewer’s mind. It’s putting [them in a space] like when you’re reading a book, imagining images that don’t have the characters. It’s interesting for me to have the characters disappearing, but you still have them because of the narration and what happened.

More than one time [during] Q&As after screenings [of the film] in different countries, people told me, “When Edward is talking on his cellphone…” And I said, “I’m sorry, but I never shot Edward speaking on a cellphone.” But then I understood what it was. There’s a moment in the film where the voiceover is talking about Edward being in a boat doing something, and you see a Chinese guy who’s the only guy in the image. You don’t have anyone else, but he’s Chinese and he’s talking on his cellphone. So people asking me about this were seeing Edward in this Chinese guy. They were projecting him onto this Chinese guy. The film was made a little bit to have this game with the viewer. They can project onto people randomly shot in place and see Edwards and Mollys everywhere because the mind works like this.

At what point do you determine how time will be represented in your films, be it in two parts like Grand Tour or backward like The Tsugua Diaries?

Cinema has an amazing potential to treat time. Alain Resnais was very obsessed with this subject of time in cinema and in the minds of people, and he’s a very important director to me. I really admire his work. Between films, I don’t write secret essays about time or something. I don’t even think about it. But it’s true that film after film, I concluded this is something that’s really compelling, how you work time in a film. It’s true in The Tsugua Diaries, and in Tabu, where I filmed older characters and then got back in the second part to some of them [when they were] much younger. What happens with the perception of a film when you do these kinds of things with time? In Grand Tour, of course, the work with time is quite central.

Do you bring in your background in film criticism and theory and intellectualize a project as you’re making it, or do you have to compartmentalize it?

To be honest, I think there’s a moment where you don’t have to think too much [about it]. You just have to feel things and sometimes do things without questioning too much the reason you’re doing it. I think there’s a moment to think more rationally, but not necessarily before and during your making the film. I think when I start to ask more questions about what I’ve done would be in the final editing. Then, you may have to have a more rational approach to what you’re creating. And before talking with film critics, you have to think, “Why have I done this?” It’s like psychoanalyzing yourself and your work. There’s a moment for doing it, and then you come to some conclusions. I don’t know if they’re real, fake, or a delusion. You have to think a little bit, but not while doing it. I think I’m very intuitive.

The motif of puppet shows, beyond highlighting the local storytelling cultures, also harkens back to the proto-cinema days of the medium’s birth. Do you see any connections between puppeteering and filmmaking?

I see all the connections. I think it’s pretty clear that they came from the same place. There’s even a form of puppet show done in Malaysia and the south of Thailand, which is the shadow puppets. We have some scenes with this kind of puppet show in Grand Tour, and it’s really cinema because the viewers are facing a screen. Behind the screen, there’s this puppet master performing, and you see the shadows of the puppets. This was happening many years before cinema was invented, so it’s really pre-cinema. Popular cinema comes from there, and for me, it was important to mix our Western puppets called Molly and Edward with the Asian puppets that we came across while we were making the journey.

How did “Beyond the Sea” come to be the final song of the film?

Every piece of music in my films appears in different moments of the process of making the films. So, in this case, it came almost at the end. Normally, because I don’t have a driver’s license, I go by bus to the editing room. But sometimes I’m late, and so in that moment, I took a taxi. On that day, I entered this taxi to go to the editing room, and he was listening to “Beyond the Sea.” It’s a catchy song, no? When I arrived to the editing room, I said, “I was listening to this song on the radio, let’s try it in the final scene.” And we thought it was great. If I wasn’t late, I would never have heard that music, and I guess that we would have a different song.

At the risk of overinterpreting, I felt like the journey in the film is encompassed in the journey that the song has taken. It started off as the French song “La Mer” about the sea and nature, and then when it was adapted in English as “Beyond the Sea,” it became a love song. Those are the two parts of the film.

It was by chance! But the lyrics of Bobby Darin’s version connect with what happens with the character in that moment of the film, of course. But I was also thinking, “I really like Finding Nemo, and this is the Nemo [closing credits] song, so it’s a good song for Grand Tour too.”

You create such space for the viewer to participate in creating the meaning of Grand Tour. Do you see your films like puzzles to be solved, though, as so much contemporary cinema has become?

No. David Lynch always tried to avoid this. [Regarding] interpretations of Mulholland Drive, he always said, “I designed these scenes. I think they’re great. I like the mystery. I don’t like the solution.” And I think he’s right. The idea of a puzzle is that pieces will [go together] and [create] a stable, final object. Sometimes, the pieces don’t really fit. And that’s good too. I would say it’s too rational—the perspective of something like a detective film [revealing who killed] someone. There’s beauty in a construction where sometimes you have missing parts, and you have to do a little bit of work yourself. But this work should give pleasure.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.