![]() “Believe what you feel and know you’re right because/The time will come around when you’ll say it’s yours,” croons Lena Horne as Glinda the Good Witch of the South (not the North, as in L. Frank Baum’s original show) near the climax of 1978’s The Wiz, a mega-budget adaptation of the funky all-Black Broadway reimagining of Baum’s Oz universe. Cinema history is littered with the shadows of what might have been but never was. But at least in the case of The Wiz, arguably the only all-Black Hollywood studio super-production until Spike Lee’s Malcolm X, it’s both a wonder and a testament to the kindness of the fates that something the benefit of 20/20 hindsight has cast as a true outlier managed to slip through.

“Believe what you feel and know you’re right because/The time will come around when you’ll say it’s yours,” croons Lena Horne as Glinda the Good Witch of the South (not the North, as in L. Frank Baum’s original show) near the climax of 1978’s The Wiz, a mega-budget adaptation of the funky all-Black Broadway reimagining of Baum’s Oz universe. Cinema history is littered with the shadows of what might have been but never was. But at least in the case of The Wiz, arguably the only all-Black Hollywood studio super-production until Spike Lee’s Malcolm X, it’s both a wonder and a testament to the kindness of the fates that something the benefit of 20/20 hindsight has cast as a true outlier managed to slip through.

And, at least in the hearts of its underserved audience, the film flourishes to this day. Odie Henderson, in his Blaxploitation survey Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras, surmised “The Wiz is far from a great movie, but it’s also more than a cult classic. There is genuine love for the film all throughout Black America, even today.” There’s a reason why, when actress Erika Alexander speaks to Horne’s 11th-hour cameo in the recent Justin Simien-helmed docuseries Hollywood Black, she can barely hold back tears. They’re tears of gratitude, yes, but also arguably intermingled with the sense of sadness that comes from understanding that the film’s very existence as a signpost of Black excellence is a lonely one—that its standing as a cherished cultural touchstone among Black audiences is, by virtue of the palpable lack of subsequent Black blockbuster film projects in the wake of The Wiz’s box office failure, a default position.

Film fans have put decades of (white) skin in the game minimizing the achievements of The Wiz. And in trying to set the record straight here, I’m painfully aware that even the Criterion Collection’s heroic selection of the film to be canonized alongside the varied likes of Seven Samurai, Jeanne Dielman, Female Trouble, and This Is Spinal Tap has only opened up another chance for the film to be broadly undervalued, and not limited to the usual gatekeeping on Criterion fan forums. As of this writing, the release hasn’t been reviewed by any of the usual suspects, and even Criterion’s website neglected to clear space with a splash graphic on the week that the disc was released, instead counterprogramming an extra week’s worth of promotion for the forthcoming comprehensive Wes Anderson mega-box. (If there’s a canonical antithesis to The Wiz, it may well be Anderson’s increasingly rigid, stuffy, cloistered filmography.)

It may seem circumspect to spend so much time documenting the current cultural context framing how certain films attain canonical status (and others don’t), but in reality The Wiz itself carries so much water for an entire cultural legacy that led up to its production that it’s hardly out of pocket to carry the baton in that regard. And, frankly, the varied ways the film interfaces with that legacy aren’t necessarily regarded as progressive, either now or back then.

Director Sidney Lumet surrounded himself with a largely white creative team behind the scenes: cinematographer Oswald Morris, production designer Tony Walton, makeup artist Stan Winston, screenwriter Joel Schumacher, and a veritable who’s who of high-fashion designers, including Ralph Lauren, Bill Blass, Norma Kamali, and Halston. But while Lumet’s primary contribution to the project would appear to have been to position the film’s Oz universe squarely within the context of “Fun City”-era New York City, there’s no denying the film’s relentlessly rich panoply of specifically Black American signifiers along the way, all feeding into the fantasia on urban decay and civic betrayal that was, upon the film’s release, extremely au courant.

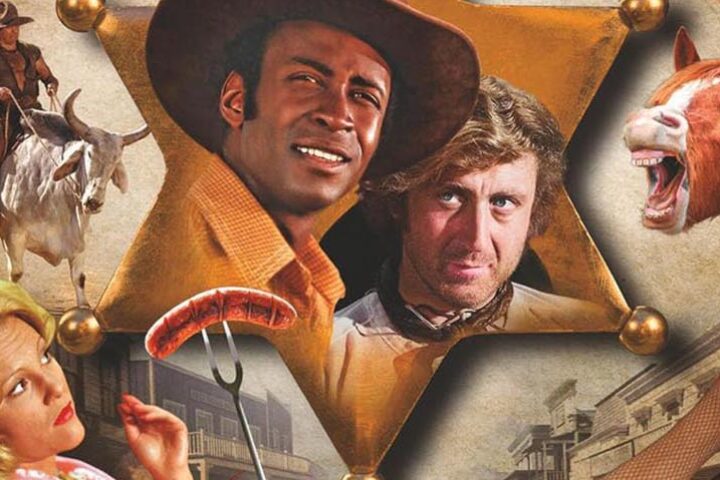

The unavoidable problem is, most of those signifiers are the negative stereotypes that white culture popularized in the first place. For one, the rubber-limbed Scarecrow (Michael Jackson, in his winningly charismatic film debut) is introduced being restrained in place mentally, if not physically, by the discouraging snipes of a flock of jive-talking crows straight out of Dumbo. And the Tin Man (Nipsey Russell, ever the consummate showman) is first seen at an Oz-ified Coney Island, being physically pinned down by his no-longer-animate wife Teeny, a hulking metal “mammy” who rolled on top of him when the carnival dried up.

Elsewhere, the emergent confidence of the Cowardly Lion (an ebullient Ted Ross, one of the few holdovers from the original Broadway cast) manifests itself in pimp-speak overtures. The flying monkeys of Baum’s universe are here reimagined as foul-mouthed, stench-ridden motorcycling apes, and the dangerous opioid-adjacent “poppies” are now 42nd Street (G-rated) hookers. It’s impossible to reconcile this iconography against the whiteness of the film’s key makers without some measure of cognitive dissonance. But if white creators were broadly responsible for affixing these cartoons to our collective consciousness in the first place, there’s a little something to be said for The Wiz as a gesture of atonement, given all principal players are positioned to rise up against them and transcend their origin stories.

No one transcends more palpably than Diana Ross. She inhabits the role of Dorothy as less the naif girl standing on the precipice of womanhood we’re so familiar with, vis-à-vis Judy Garland’s incarnation in 1939’s The Wizard of Oz, and more an adult who mentally hasn’t caught up to her age just yet. In this version, she’s a Harlem schoolteacher whose Auntie Em (Theresa Merritt) regularly reminds her has “never been south of 125th Street.”

Critics with their knives out for the film homed in on Ross’s age and the impenetrability of her star persona to pin much of the blame for the film’s failure on her supposed miscasting. It’s true that, circa 1978, someone of Ross’s stature playing a Dorothy suffering from “failure to launch” syndrome is akin to, say, Beyoncé tackling the role of Adrian in a musical remake of Rocky. Again, though, time has been reasonably kind to Ross’s full-throated embodiment of self-actualization as a life-long journey, not a destination one simply reaches by this age or that. And the distance she clocks from hiding in the pantry to warble “Can I Go On?” while hiding from her relatives on Thanksgiving to, in the film’s stunning final minutes, holding down the center of the universe while belting a battleship rendition of “Home” is just that, a journey.

In addition to the copious Black talent in front of the cameras, there were a few key Black players working the craft side of the aisle as well whose contributions can’t be overstated enough. Chief among those were choreographer Louis Johnson, whose exuberant work on the “Brand New Day” liberation ballet (culminating in a dizzying storm of jubilant sidekicks) does as much as anything in the film to underline its commitment to expressions of Black joy, and overall MVP music supervisor-orchestrator Quincy Jones.

Q’s imperial phase arguably kicked off with his work here, not only because it marked the moment when he and Jackson first forged the working relationship that would soon dovetail into the landmark Off the Wall and Thriller projects, but because Q as much as anyone understood the assignment: sheer, unabashed, virtuosic excellence. Those who hold The Wiz fondly in their hearts do so largely because the film embodies the “O-P-U-L-E-N-C-E” that Junior LaBeija a decade later would coin a catchphrase around in Jennie Livington’s Paris Is Burning, and nowhere is that more evident than in its soundtrack.

Some have argued that Q’s arrangements bury the original material’s modest charms, but modesty was clearly never the project’s aim in the first place. For Q, it wasn’t enough to assemble an orchestra big enough to be two, as he also brought aboard the most polished L.A. musicians available: Randy Brecker, Steve Gadd, Bob James, Harvey Mason, Paulinho Da Costa, Anthony Jackson, and Jerry Hey. The double album soundtrack is, in practice, yacht rock, and the glint of its sheen is its own reward. But Q is also highly tapped into the film’s aim to fold as much of the Black cultural experience into its every fiber, drawing on the traditions of ragtime, blues, disco and gospel with equal dedication (even tossing in a sly “Sesame Street” quote into the “Brand New Day” ballet, in tribute, while Nipsey Russell ad libs, “Free at last”).

Fueled by the finest, most aurally expensive-sounding suite of music Q ever mounted, the entire project arguably reaches its apotheosis in the centerpiece Emerald City sequence. It’s a seven-minute extravaganza positioned on the plaza between what were then the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, and a scene invented entirely to parade gilded arrival (for both the hop-skipping, Oz-questing quartet and for the film itself).

But there’s a double-edged element to this sequence. On the one hand, it’s hard not to be knocked flat by the sheer scale of the scene. Lumet shot it first up, before anything else, both to get the most demanding production hurdle out of the way early, but also one imagines to establish a tone of epic scope from the outset. As Dorothy and her crew roll up to the plaza, they’re notably halted in their tracks by the magnificence of the Oz denizens parading their haute couture. On the other hand, it soon becomes apparent that the throngs are changing on a dime when announcements from above dictate that fashion has changed course and new colors are now “in.” By the time they’ve shed their green duds to don red, and cast off their red gear to latch onto gold, you can’t help but also notice that the great washed masses are also stuck promenading in an endless circle, looking drop dead while going absolutely nowhere, all in service of a higher power who will soon enough be revealed to be an utter charlatan.

Like all truly mythic texts, The Wiz issues its own self-critique. If you choose to chase the dream society dictates for you, you will watch as it mocks your quest to live up to others’ expectations. In that sense, there’s some poetic justice that The Wiz’s contemporary “failure” gave Hollywood an excuse to divest from Black cinema entirely. Because that act of abandonment also arguably helped loosen the shackles from Black entertainers from the old goal of “mirroring” white intellectual property, setting future generations free to forge their own narratives.

Image/Sound

Criterion has gotten to the point where nearly all new releases are made available on 4K, but it’s still heartening that they saw fit to opt for a UHD presentation for a film that, it can’t be stressed enough, radiates opulence. Working from a new digital restoration sourced from the original camera negative, the film has frankly never looked so vibrant, so lavishly expensive.

In the disc’s commentary track, it’s noted that Sidney Lumet never meets a wide shot he doesn’t love, which is among the movie’s charming flaws. But rewatching the film for the umpteenth time, this time on a large TV set with 4K capabilities, I was astonished by how much detail and sparkle had eluded me in all my prior home viewing. The long, high shot of Dorothy and the rest crossing an ersatz Brooklyn Bridge as dusk rapidly falls and the jade jewel tones of the Emerald City start flickering across the lower Manhattan skyline is but one of many such revelations on display here. It’s truly as revolutionary an upgrade as I’ve seen in recent years.

The main technical failing, alas, is the lack of any audio track other than the newly remixed Dolby Atmos surround. It’s not that the soundtrack isn’t finely calibrated; it is, utilizing Quincy Jones’s 24-track original recordings. But one wishes there could have been an original soundtrack option even just as an alternate, because among other things the remix incongruously loses a few (very minor) audio elements and lines of dialogue. None crucially important, but it’s definitely noticeable if you, like me, are among the movie’s rabid fans.

Extras

In the case of The Wiz, I’m firmly in the camp of “just give me the best-looking, best-sounding version of the main feature and I’m good.” But, because the critical reputation of The Wiz is so virulently contested, it’s heartening that Criterion went the extra distance to include not just a typically well-argued booklet essay, this one by critic and podcaster Aisha Harris, but also an expertly conducted feature-length commentary track.

Scholars Michael B. Gillespie and Alfred L. Martin turn in top-notch work on their track, analyzing the film’s position in Black cinema history, detailing the finer points of its production, paying tribute to the genuinely emotional connection it retains with its cult audience, and at times allowing themselves to get caught up in the splendor of its mere existence. From Martin, with his dancer’s background, delving into the politics of what “clean” dancing means in the context of the film’s akimbo choreography, to the two of them sucking in a gasp upon the arrival of that aforementioned shot of lower Manhattan (in which the rising sun is replaced by, of course, a Big Apple), this is a track made by, and for, unabashed fans of The Wiz.

One does wish that there were more historical supplements, beyond two brief clips featuring Diana Ross attending the film’s splashy premiere and Sidney Lumet (circa 2001) discussing his recruitment of Quincy Jones, but as Gillespie and Martin’s track even mentions, the film’s box-office failure ultimately meant its archival prospects were automatically deemed somewhat dispensable. That being said, the almost shocking level of contempt on display from the reporter packaging his interview with Ross speaks volumes about the film’s initial critical reception.

Overall

For any number of socio-political reasons, The Wiz may never get its canonical due, but thanks to its induction into the Criterion Collection, it’s moving one big step in the right direction.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.