![]() Some three decades after its release, it’s disheartening, yet perhaps not surprising, that more filmmakers haven’t looked to François Girard’s singular Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould for inspiration on how to break free from the stifling conventions of the modern biopic. And because of the deadening uniformity of the genre, Girard’s film appears all the more miraculous in retrospect.

Some three decades after its release, it’s disheartening, yet perhaps not surprising, that more filmmakers haven’t looked to François Girard’s singular Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould for inspiration on how to break free from the stifling conventions of the modern biopic. And because of the deadening uniformity of the genre, Girard’s film appears all the more miraculous in retrospect.

From its rigorous and deliberately distancing structural gambit to its restless stylistic experimentations, Thirty Two Short Films proves that biopics needn’t color within the lines to effectively portray their subjects. But more importantly, it shows that by approaching said subject with a kaleidoscopic spectrum of aural and visual conceits, the biopic is capable of unlocking a deeper appreciation for and understanding of them. And certainly to a degree that can’t be attained through mere historical and biographical details and re-enactment.

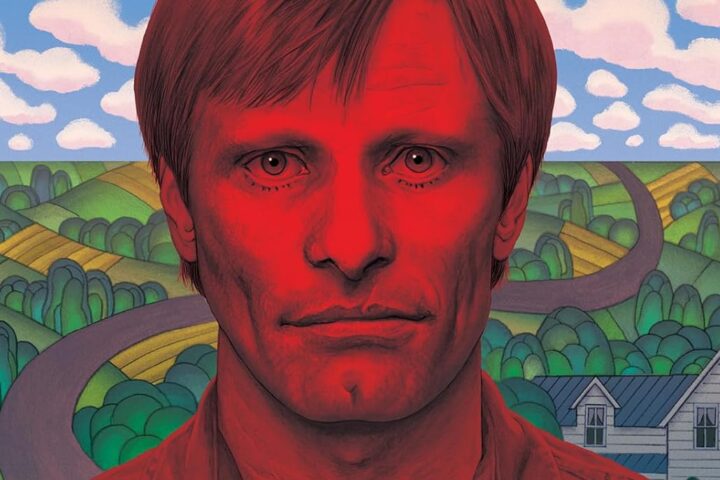

Of course, Girard’s film is cognizant that its subject, the famed Canadian classical pianist Glenn Gould, must be fictionally embodied in some way. And it does so initially in the second of its 32 short films, following a brief prologue, with a 45-second slow zoom into a close-up of the face of the actor, Colm Feore, who will be playing him. Yet, in prefacing this shot with a title card (“45 Seconds and a Chair”), Girard calls attention to the artifice that’s so deeply intertwined with his presentation of the legendary artist. This reminds us from the get-go that Feore is but an avatar, shifting our connection to Gould from emotional to intellectual, and our attentions from his individual psychology toward his music and approach to art.

Fittingly, all of the shorts that comprise Thirty Two Short Films are introduced with their own separate title cards. This tactic disrupts the film’s continuity in such a manner that even the few stretches that verge on direct biographical representation are rendered as small fragments of the larger, more abstract portrait that Girard, co-writer Don McKellar, and editor Gaétan Huot stitch together, eschewing the hagiography bent of so many “great man” biopics.

Along with mirroring Gould’s structural approach to music and referencing his recording of “Beethoven’s 32 Variations in C Minor,” the narrative structure that Girard and McKellar impose on their film allows for a playful and invigorating mélange of documentary, fiction, and avant-garde techniques. Interviews of some of Gould’s actual friends and family brush up against various pieces by Gould playing over a shot of the film’s optical sound strip or sweeping tracking shots of the interior of a Steinway piano. There’s even a short animated sequence as well as one showing Gould playing the piano in X-ray vision as the pianist’s diary entry’s obsessively recording his blood pressure are read in voiceover.

Aside from giving the audience something formally inventive and uniquely captivating at nearly every turn, Thirty Two Short Films deliberately heightens and sharpens our auditory senses, using images to highlight and connect us to the music itself. It does so primarily through structural absence, specifically by never having Feore, as Gould, pretending to play the piano for the camera, thus removing our instinctive emotional response to Feore in these sequences and instead directing our minds and ears to the musical notes themselves.

For all its aesthetic experimentation, Thirty Two Short Films is exceptionally unified—each segment approaching Gould, and his work, from a new angle. Yet, unlike most biopics about great artists, Girard’s film understands that no straightforward, biographically comprehensive film can get us close to their way of seeing, hearing, and experiencing the world. It neither contributes to nor fully punctures the mythology surrounding Gould, shrewdly presenting him as both man and enigma and offering an incomplete portrait that still gets right at the heart of what makes him such an unparalleled figure in his field.

Image/Sound

Transferred from a new 4K restoration, Criterion’s presentation features an image rich in detail. There’s an impressive range of warm autumnal tones in many scenes, while the winter-set sequences are suitably cool, with blistering whites and icy blues dominating the color palette. Fitting for a film so explicitly focusing on music, the audio steals the show here, with the 5.1 mix presenting Glenn Gould’s music with depth and resonance, while the scenes in the diner and Gould’s recording booth, where the film highlights the pianist’s ability to fully comprehend several conversations at once, show how carefully the audio tracks are layered.

Extras

Writer-director François Girard and co-writer-actor Don McKellar’s new audio commentary gets into the nitty gritty of their research process, how McKellar initially became involved with the project, and how they made various decisions regarding the unusual structure of the film. It’s a lively conversation that also touches on much of Gould’s career, and it’s clear that over 30 years later, both men still have a fondness for his music and their film.

In a lively 30-minute conversation between Girard and Atom Egoyan, the directors delve into the different art and film scenes in Toronto and Quebec from the 1960s to the ’80s. They also talk about how Girard, being French Canadian, approached this material with less reverence than most Toronto filmmakers would have, and how the film is all the better for it.

We also get a pair of archival interviews, one with actor Colm Feore from 2012, in which he touches on the challenges of the casting process and embodying Gould through his unusual speech patterns more than anything else, and one with producer Niv Fichman, who waxes rhapsodic about Gould and his longstanding desire to make a film about the pianist before Thirty Two Short Films came along. Lastly, there are a pair of fascinating 30-minute companion docs from 1959, which focus on his private life and recording process, and a booklet with an essay by Michael Koresky, who writes eloquently about the film’s “symphonic construction.”

Overall

With a beautiful transfer and terrific slate of extras, Criterion’s stellar 4K release celebrates the singularity of both Glenn Gould and François Girard’s biopic about him.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.