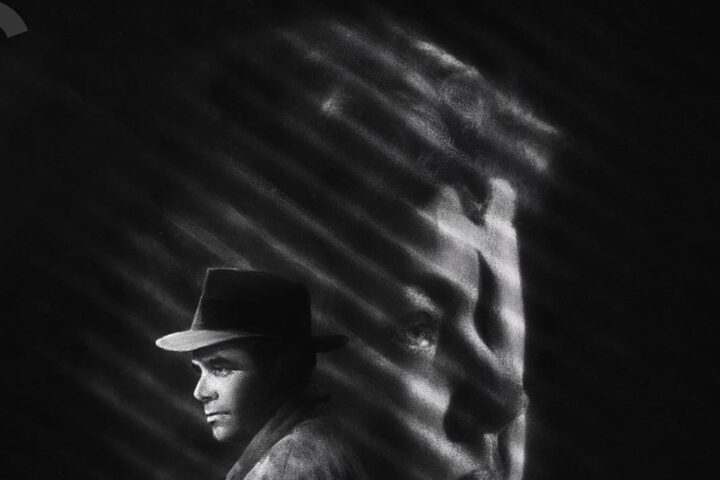

![]() Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier) doesn’t bother asking for acceptance or respect from white people. He unequivocally demands it. Unlike Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night is under no delusions that racial prejudice can be corrected merely by white people coming into proximity with intelligent, successful people of color, particularly in a small town like Sparta, Mississippi. Tibbs dons a slick suit, employs a vivid vocabulary, and carries himself with an aura of confidence and import. But he knows he’s in the Deep South, and when he’s arrested in humiliating fashion by Officer Sam Wood (Warren Oates), and with no questions asked, Tibbs wisely stays mum and allows himself to be roughly escorted to the police station.

Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier) doesn’t bother asking for acceptance or respect from white people. He unequivocally demands it. Unlike Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night is under no delusions that racial prejudice can be corrected merely by white people coming into proximity with intelligent, successful people of color, particularly in a small town like Sparta, Mississippi. Tibbs dons a slick suit, employs a vivid vocabulary, and carries himself with an aura of confidence and import. But he knows he’s in the Deep South, and when he’s arrested in humiliating fashion by Officer Sam Wood (Warren Oates), and with no questions asked, Tibbs wisely stays mum and allows himself to be roughly escorted to the police station.

The film doesn’t satisfy expectations of a traditional narrative structured around an innocent Black man struggling to prove his innocence. When presented to the town’s police chief, Bill Gillespie (Rod Steiger), Tibbs angrily tosses his Philadelphia police badge on the man’s desk, not only insisting on the respect that he’s earned, but taking special joy in boasting of his higher salary and position as Philly’s elite homicide investigator. And while Tibbs’s professional standing causes Gillespie to straighten his shoulders and drop the condescension long enough to all but beg Tibbs to stick around and help out with the homicide investigation, the antagonistic nature of their initial encounter hangs like a dark cloud over the remainder of Jewison’s film.

As the two cops begin the tumultuous process of collaboration, Poitier and Steiger play off one another like two great jazz musicians, using prolonged silences and explosive bursts of pent-up rage with equal aplomb as Tibbs and Gillespie struggle to balance their innate suspicion of one another with the dawning realizations that they must rely on each other to solve a crime. And it’s their precarious and often combative relationship, with the men wavering between intense distrust and making strides to strengthen their alliance during their investigation of Phillip Colbert’s murder, that becomes the guiding principle of the film.

Across scenes that are occasionally thick with disdain, In the Heat of the Night depicts the Sparta locals who are tangentially tied to the murder investigation, but the offbeat humor of these scenes also provides a much-needed levity to the film’s otherwise tense proceedings. Everyone from the aforementioned Sam and the diner owner, Ralph (Anthony James), to Gillespie’s assistant, Courtney (Peter Whitney), are amusing Southern-fried caricatures, but beneath their goofy exteriors lurks something strange and unsettling. Such scenes as Ralph putting the satirical country song “Foul Owl on the Prowl” on the jukebox and awkwardly dancing around the diner get at how this lifestyle of the rural South is fundamentally incompatible with inclusion, especially of a well-educated Black man like Tibbs.

A dichotomy of one sort or another, such as that between Black and white or self and society, underlines almost every moment in Jewison’s film. As Gillespie uncomfortably acclimates to deferring to the professional expertise of a Black man of higher class, Tibbs copes with his initial resentment at having to rely on a racist white man as his lone protector from the many townspeople who’d, at best, run him out of town.

To the film’s credit, neither of the men’s flaws are swept under the rug. Tibbs’s calm, collected demeanor conceals a brewing undercurrent of indignation that mutates into an impulsive vengeance which drives him to stay in Sparta even after the townsfolks’ death threats become more serious. And while Gillespie grows to admire Tibbs for his skills as an investigator, his prejudices are too deeply embedded to allow a true kinship between them to flourish. Where similar “biracial buddy” films build to a sense of racial unity between their main characters, naïvely suggesting that a white person’s long-held prejudices have been forever eradicated, In the Heat of the Night embraces a more nuanced understanding of how people evolve.

In a complex, emotionally disarming scene late in the film, Tibbs visits Gillespie at his home, where the latter suddenly begins to open up and speak about his loneliness. After asking Tibbs if he’s ever lonely, Tibbs tenderly replies, “No lonelier than you, man,” offering his own feelings of isolation as an olive branch. But Gillespie responds hostilely: “Now, don’t you get smart, Black boy.” The man bristles at receiving even a hint of pity from someone who, in some ways, he will always see as an inferior. Soon after this contentious encounter, the filmmakers attempt to bridge the gap between the two men, as Tibbs boards the train heading out of town and Gillespie musters up an amiable, “You take care, you hear?” The two men smile in a sort of tacit admission of mutual respect after having caught the murderer.

James Baldwin astutely referred to this moment as a form of reconciliation akin to that of a movie kiss. But by positioning this final scene of supposed racial harmony so soon after the earlier moment when Gillespie’s prejudice resurfaces with a vengeance, the film takes on a bittersweet quality. The men’s final goodbye portends hope while subtly, yet cynically, acknowledging that Gillespie’s feelings of camaraderie with a Black man are fleeting, that his racism will almost certainly endure long after Tibbs’s train has pulled out of the station.

Image/Sound

Criterion’s transfer for this release uses the same 4K restoration that Kino Lorber used for its 2022 4K UHD, and as such the image presentations are unsurprisingly very similar. Image detail and depth is impressive throughout, but especially in the nighttime sequences, where the inky blacks and high contrast make virtually every inch of the frame clearly visible. Criterion’s 2019 Blu-ray only came with mono audio, so the addition of a 5.1 surround track (the same one, incidentally, included on Kino’s 4K UHD) is another marked upgrade from that release.

Extras

All the extras here have been ported over from prior Criterion releases. The 2008 commentary track by Norman Jewison and Haskell Wexler is a nicely balanced discussion of the film—its themes, historical context, often experimental shooting methods, and more. Jewison speaks mostly to the film’s social import and performances, charting the personal and professional relationship between Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger. Wexler, for his part, offers seemingly endless technical insights, about everything from his expressive use of mesh and screens to achieve a more textured look in numerous shots and tricks he learned from Raoul Coutard.

In an interview recorded for the 2019 Blu-ray, Jewison provides context for his decision to imbue the film with humor and discusses his working relationship with the film’s editor, Hal Ashby. In another interview recorded for that release, Lee Grant discusses the tender scene where Poitier’s Virgil consoles her character after her husband’s murder, as well as voices her anger at being blacklisted. There are also interviews with Poitier and Aram Goudsouzian, author of Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon, that touch on the actor’s political beliefs, his rise to fame throughout the civil rights movement, and his frustrations with Hollywood for depriving his characters of sexuality so that he can be deemed “safe” for white audiences.

Elsewhere, the film’s wildly eclectic soundtrack is given its due in “Quincy Jones: Breaking New Sound.” The disc also includes a short documentary, “Turning Up the Heat: Movie-Making in the ’60s,” a theatrical trailer, and a booklet with a shrewd essay by K. Austin Collins that delves into the film’s depiction of racial intimacy and complex juxtapositions of rage and pride.

Overall

Criterion’s new 4K UHD release of In the Heat of the Night may not come with any new extras, but it offers a nice boost in A/V presentation from the label’s 2019 Blu-ray.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.