![]() The tension between uncovering hidden aspects of film history and respecting the lives of those contained within it form the undergirding conflict of Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman, a film of such multitudinous interests and storytelling pursuits that it replicates the ecstasy of newfound romance. The film’s crux, beyond the blossoming lesbian relationship at its core, is Dunye’s aligning of hidden historiographies with the hassle of dating—of searching for something (or someone) that, at the surface, cannot be immediately seen with the naked eye.

The tension between uncovering hidden aspects of film history and respecting the lives of those contained within it form the undergirding conflict of Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman, a film of such multitudinous interests and storytelling pursuits that it replicates the ecstasy of newfound romance. The film’s crux, beyond the blossoming lesbian relationship at its core, is Dunye’s aligning of hidden historiographies with the hassle of dating—of searching for something (or someone) that, at the surface, cannot be immediately seen with the naked eye.

Dunye establishes the problem of incomplete histories as Cheryl (Dunye) and Tamara (Valarie Walker) debate the value of, as Tamara puts it, watching “mammy shit from the ’30s.” They do so from behind the counter of a Philadelphia video store, where their employ is less driven by cinephilia—though Cheryl clearly knows her shit—than economic necessity. Unlike Kevin Smith’s Clerks, which uses dead-end jobs for ironic, low-stakes altercations between its characters, The Watermelon Woman views Cheryl’s daily grind as a complex formation of potentially conflicting passions and motivations that has the potential to both reveal the past and shape her future.

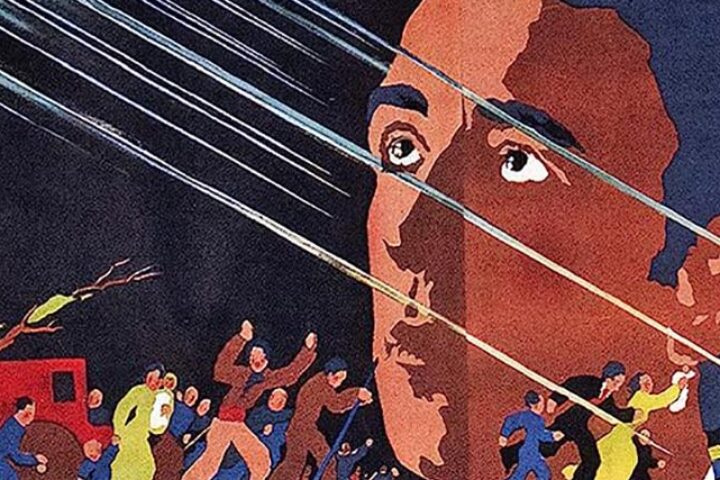

The film’s title refers to a Black actress during the ’30s whose billing name was “the watermelon woman.” As an aspiring documentary filmmaker, Cheryl combs through films from the silent and pre-Code era in search of such “mammy” types, and becomes obsessed with uncovering not only the woman’s (Lisa Marie Bronson) real name, which she discovers is Fae Richards, but also more about her life. Dunye establishes Cheryl’s intrigue with a sleight of hand that plays with the divide between fact and fiction, so that The Watermelon Woman suggests Richards is an actual person when, in fact, she’s a fictional character conceived by Dunye.

Yet the film plays Cheryl’s search for evidence about Richards’s life as if it will teach the viewer about actual dimensions of film history. By playing the lead role, Dunye makes no distinction between these fabrications, her character’s sexual preferences, or even herself as both a filmmaker and a lesbian: Each of these elements exists along a continuum of varying shades of verisimilitude so that the newness of seeing Black, lesbian women on screen is paralleled by Dunye’s creation of a Black actress from a past era. So little is known about Black women who were acting in the ’30s, whether in their personal or professional lives, that the film’s narrative liberties excel past a simple play with its essentially mockumentary form.

On a conceptual level, the film takes the historical suppression of Black actresses and filmmakers and plugs it into a present tense, where Cheryl is infatuated with Diana (Guinevere Turner), a white woman who’s just moved to Philly from Chicago. Tamara contests Cheryl’s choice in women, specifically white women, which leads Cheryl to counter: “Who’s to say dating somebody white doesn’t make me Black?” Cheryl’s rebuttal could easily be altered to speak for Richards, and for Dunye’s film, to read: “Who’s to say being fictional doesn’t articulate a truth?”

These dynamics of identity politics and historical recovery are complicated even further when Cheryl visits feminist academic and social critic Camille Paglia at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. There, Paglia professes that the mammy archetype is a powerful “symbol of abundance,” particularly within Italian culture. Paglia’s testimony both brings a bit of historical clarity to Cheryl’s research as well as extends the pathway to reaching a final destination of certainty. Turns out, the more Cheryl learns, the more complex the matter becomes.

The Watermelon Woman champions recovered knowledge as the primary means to reverse the systemic erasure and closeting of gay histories. As Cheryl says near the film’s beginning, her films “have to be about Black women, because our stories have never been told.” It’s doubly remarkable, then, that this bedrock of New Queer Cinema should construct a fictitious backdrop of its own in place of an actual, overlooked one. In doing so, Dunye both complicates the historicizing process and makes a trenchant statement against any narrative that either naturalizes its subject matter or believes too haphazardly in its own revisionist significance. It’s the combination of past and present—a cinematic stabilization of historical necessity and contemporary lesbian romance—that gives the film its singular identity.

Image/Sound

Sourced from a 2K digital restoration, Criterion’s transfer boasts a high dynamic range of colors, making the most of the frequent use of pinks, purples, and blues throughout the film. The video footage, used for the documentary that Cheryl Dunye’s character is making in The Watermelon Woman, is appropriately as crummy as mid-’90s home video typically looks, while the bulk of the film, shot on 16mm, looks vibrant and crisp with even and surprisingly tight grain. This restoration already looked quite good streaming on the Criterion Channel, but the Blu-ray adds even more detail and depth to the picture. On the audio front, the surround track more than gets the job done, with the dialogue consistently coming through crisp and clear.

Extras

In a new interview, Dunye discusses the controversial response to the film, which almost caused her to lose thousands of dollars in NEA funding, and how her home city of Philadelphia and its Black history influenced her art. In a separate conversation, Dunye and artist and filmmaker Martine Syms talk about queer Black representation and how they use metatextual elements in their work as a means of reflecting their marginalization. A second conversation between producer Alexandra Juhasz and filmmaker and film scholar Thomas Allen Harris touches on their friendships with Dunye and how Juhasz helped Dunye branch out into feature films and navigate the film festival scene. Rounding out the package are six of Dunye’s early shorts and a booklet with an essay by critic Cassie Da Costa that teases out the complexities of the film’s theme of missing Black history and the presentation of the central, interracial relationship.

Overall

Cheryl Dunye’s feature debut remains as sensual, funny, and incisive as the day it was released.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.