Nestled between the epic sprawl of the first two Godfather films, The Conversation allowed Francis Ford Coppola to engage in a more personal style of storytelling. With it, he crafted a small-scale character study steeped in minor-key melancholia, as well as gave free reign to his infatuation with the international arthouse cinema of the time.

A shout-out to Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-up, The Conversation perfectly encapsulates the disaffection, alienation, and paranoia infecting America’s body politic in the era of Watergate, the wiretapping scandal that brought down the Nixon administration, though the timing of the film’s release was coincidental. By some act of synchronicity, Coppola opted to focus on a surveillance expert, Harry Caul (Gene Hackman at his most buttoned-up), who utilizes the same sort of hardware as G. Gordon Liddy and the other Watergate “plumbers” while in the employ of a corporate bigwig known only as the Director (an uncredited Robert Duvall).

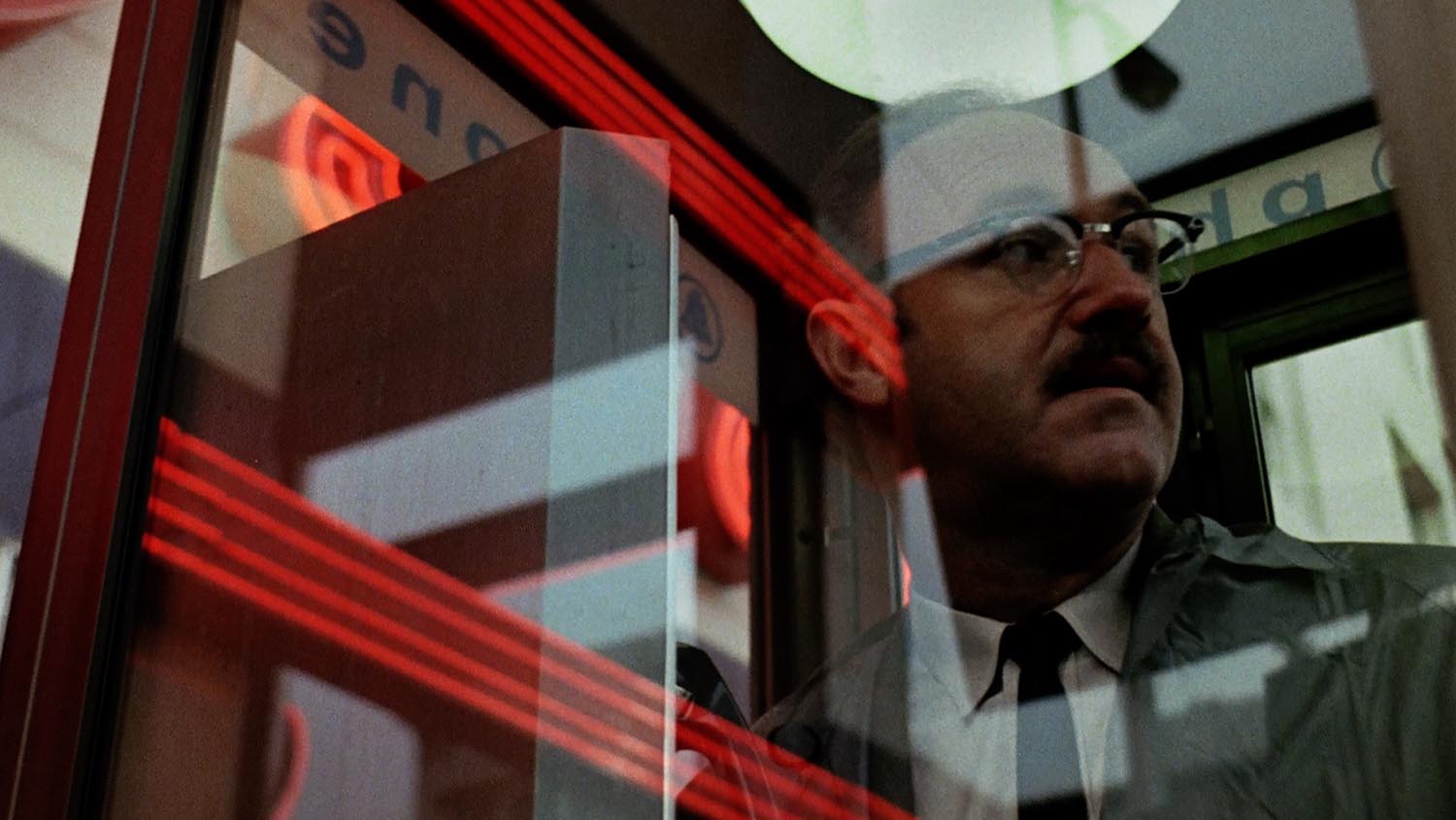

Harry’s assignment is to record a conversation between a young couple, Ann (Cindy Williams) and Mark (Frederick Forrest), as they nervously perambulate around San Francisco’s Union Square. Throughout, Coppola and cinematographer Bill Butler use long lenses and extreme zooms to mirror the surveillance team’s state-of-the-art equipment, an aesthetic choice that continues in the often static, passively observational camera placement during later scenes.

The opening shot is one of these slow zooms that moves down from a God’s-eye view of Union Square. (Haskell Wexler was the film’s original cinematographer, and his footage was reshot except for surveillance scene in the plaza.) Only later will the viewer realize that it stands in for the POV of a boom-mike operator, eerily resembling the lone gunman in yet another political assassination scenario, perched atop a nearby building. But The Conversation largely eschews the overtly political, burrowing down deep into the quagmire of personal relationships.

At the outset, Harry, the consummate professional, claims that he couldn’t care less about the conversation’s content, as he’s interested only in getting a “nice, fat recording,” made possible by his formal and technical prowess. As Coppola’s film progresses, though, it’s increasingly apparent that the man’s restraint, a desperate feint at objectivity, stems from a profoundly traumatic source, the murderous upshot of one of Harry’s earlier assignments.

Consequently, Harry has insulated himself from any encroachments of human fellowship. Rather than professionalism, a sense of responsibility and guilt emerges as Harry’s prime motivator. Coppola brilliantly aligns these concerns in a brief scene where Harry goes to confession, the only space in seems in which he can truly open up. As he expresses his darkest fears, the camera executes a slow rack focus from Harry’s profile to the confessional booth’s screen, then through to the ear of the priest hearing his confession.

The confessional booth’s screen is another in The Conversation’s diaphanous surfaces that simultaneously hide and reveal. Further instances include the sheet of plastic hanging in Harry’s warehouse office sanctum, the glass partition between balconies at the Jack Tar Hotel, and the clear raincoat that Harry always wears, regardless of the weather’s clemency. Add to that the fact that “caul” refers to an amniotic membrane that sometime covers a newborn’s head, often linked in folklore traditions to prophetic powers. This accounts for Harry’s strange dream in which he sees Mark and Ann being murdered by the Director. But considering the actual outcome of events, Harry’s vision is given an ironic final turn of the screw.

“Who started this conversation anyhow?” Mark asks at one point during one of his peregrinations with Ann. Their dialogue is reiterated throughout the film, as Harry fills in its blank spots, and each time parts of it take on new meaning. One line, in particular, signals radically different consequences depending upon its intonation. In a larger sense, repetition serves as The Conversation’s thematic keystone. Harry acts to prevent the same thing happening again as a result of his work, inadvertently contributing to the certainty that it will.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.