![]() In a 1999 interview with LA Weekly, Armond White said, “Spike [Lee] has become a first-rate marketer—he knows what a young audience wants, and he supplies it. Spike picks hot topics—basketball, interracial dating—but that doesn’t mean you break ground. Barbara Walters picks hot topics every day. The pretense of seriousness doesn’t mean you’re serious.” In defense of Charles Burnett’s 1977 masterpiece Killer of Sheep, White, who wrote a piece on the film for The A List: The National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films, also suggests that Burnett, not Lee, shows black American life as it really is.

In a 1999 interview with LA Weekly, Armond White said, “Spike [Lee] has become a first-rate marketer—he knows what a young audience wants, and he supplies it. Spike picks hot topics—basketball, interracial dating—but that doesn’t mean you break ground. Barbara Walters picks hot topics every day. The pretense of seriousness doesn’t mean you’re serious.” In defense of Charles Burnett’s 1977 masterpiece Killer of Sheep, White, who wrote a piece on the film for The A List: The National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films, also suggests that Burnett, not Lee, shows black American life as it really is.

The way White sees it, Lee’s joints are brash and fashionable but their truths are rarely vibrant, made and marketed to appeal to the same youth that typically favors American Pie over All the Real Girls, Trainspotting over All or Nothing, and Dead Presidents over George Washington. There’s nothing wrong with accessibility, but Lee’s Hollywood success would seem to oppress the visions of true-grit independent black filmmakers like Burnett who struggle to get their films made, and then seen. Where Lee has been championed for delivering his vision of black life in America to a mass audience, the elegiac films of Burnett have gone largely ignored.

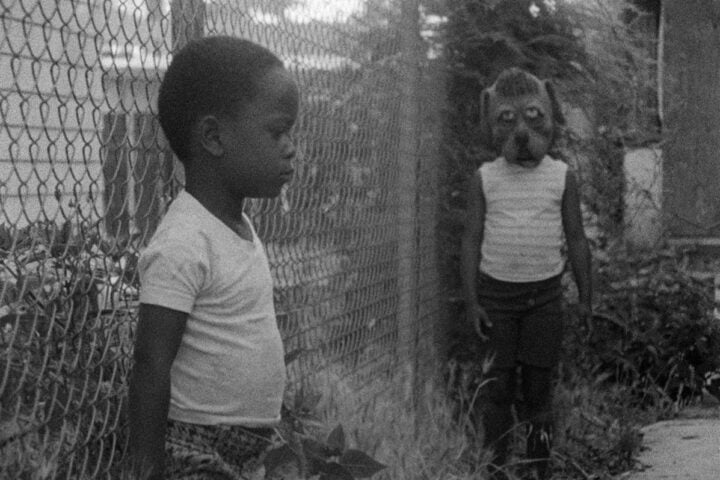

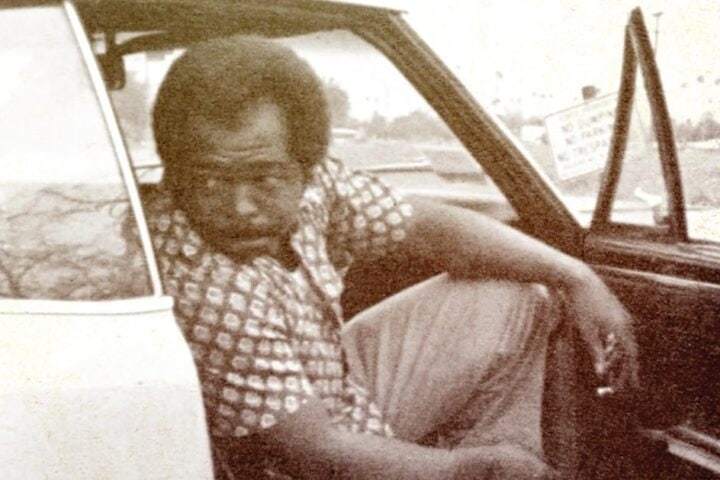

Killer of Sheep, like most of Burnett’s early films, takes place in and around the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. The fly-on-the-wall narrative observes the life of a slaughterhouse worker, Stan (Henry Gayle Sanders), grappling with poverty, misbehaving children, and the allure of violence. The film at once recalls the gritty, episodic quality of John Cassavetes’s Shadows and Faces, the lyrical mournfulness of Robert Bresson’s profoundly allegorical Au Hasard Balthazar, and Jean Renoir’s unsentimental humanity. Despite these influences, the film’s sad yet proud vision of black life in Watts is distinctly Burnett’s own, and one that would influence David Gordon Green’s wonderful George Washington.

Burnett shot Killer of Sheep over a series of weekends on a shoestring budget of just under $20,000, using friends and relatives as actors. None of these things should be taken as limitations; if anything, the film is ennobled by them. If not for its almost poetic sense of rhythm and the dialogue’s biblical overtones, Killer of Sheep could very well pass for a documentary about life in the Watts. Stan’s wife (Kaycee Moore) advises him not to engage in shady business dealings with murderous men, but not before slowly entering the frame from the dark shadows of her home’s interior and suffering through a debate on human nature that likens a man’s fists to that of an animal’s teeth. This is storytelling at once unglamorous and edifying.

Killer of Sheep is stitched together from similar such evocations of black experience in Watts—rituals of denial, desire, and disappointment, as well as modes of playtime that often veer toward the dangerous. Though Stan’s wife prevents him from being led to slaughter, he leaves her in sorrow after a dance between the couple prognosticates sex, and when kids fight near railroad tracks, Burnett frames the action using a series of abstract, tight close-ups, finding something mythic in their oddly serene antics. Burnett’s compassionate cutting gets to the root of how consciousness is passed through generations, as in the racially charged juxtaposition of Stan’s wife dolling herself up and her daughter (Angela Burnett) playing dress-up with a white doll. Burnett’s vision is unpretentious and matter-of-fact but its truths are totemic.

What distinguishes Killer of Sheep from films like Clockers is its absence of malice, which is striking given its tough view of life in Watts. Blues music plays an important role in the film, but while Burnett’s musical choices may stress the plight of his characters, the songs are also hopeful, enlarging the humanist essence of the film’s images, which convey the idea that life in the Watts is not so much about suffering as it is about persevering. That means you won’t hear Nina Simone’s “Black Is the Color of My True Love’s Hair” or Billie Holiday’s version of “Strange Fruit” on the soundtrack but Dinah Washington’s stirring rendition of “Unforgettable,” which plays over the closing image of little lambs oblivious to their impending doom.

Image/Sound

At the time of Milestone’s DVD release of Killer of Sheep almost 20 years ago, the fact that we were getting Charles Burnett’s film at all was cause for celebration, and that it also looked handsomely restored was just gravy. Now, in a new 4K digital restoration, Killer of Sheep has never looked more vibrant and teeming with detail. It was originally shot in 16mm, and while there are some limitations on close inspection, the fact remains that the dynamic range of the black-and-white images is much improved from the prior DVD, even without the benefit of HDR. (One unexpected revelation I had when watching the film anew: Could that kitchen tile behind Kaycee Moore be the same as the tile backdropping Delphine Seyrig’s meatloaf making in Jeanne Dielman?)

The monaural soundtrack included here also boasts a significant step up from the one on the prior DVD release in that it has restored the concluding needle drop of Dinah Washington’s “Unforgettable” where rights issues previously got in the way. It’s yet another testament to Criterion’s peerless commitment to getting it right, just as the entire presentation here is the culmination of decades’ worth of careful stewardship by myriad benefactors.

Extras

If there’s a single downside to this release, it’s that Burnett’s 1983 feature-length follow-up, My Brother’s Wedding, which Milestone included on its DVD release, is nowhere to be seen. Just imagine that Criterion is saving that title for its own standalone release somewhere down the line and savor the rest of what this package has to offer, including a rerack of the DVD release’s extraordinary commentary track by Burnett and film scholar Richard Peña (former program director for the Film Society of Lincoln Center). Burnett and Peña pack two commentary tracks’ worth of insight and info into the all-too-brief 80 minutes of runtime, with the director in particular offering a reliable center of gravity to the proceedings.

Also carried over from the Milestone release are two short films directed by Burnett, both predating Killer of Sheep: 1969’s “Several Friends” and 1973’s “The Horse.” The former comes off as a trial run for the feature film, whereas the latter is a bit more out-of-pocket, which may be why Burnett surfaces specifically to introduce it. (Not ported over from the Milestone release is 1995’s “When It Rains,” which film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum memorably included on his 2002 Sight and Sound ballot of the 10 greatest films ever made.)

Killer of Sheep and Burnett’s place among the wider L.A. Rebellion get dissected at length in the hour-long documentary A Walk with Charles Burnett, directed by Robert Townsend (whose Hollywood Shuffle is also notably in the Criterion Collection). And on the newer side of things, Moonlight director Barry Jenkins drops in with a 20-minute love letter, of sorts, to Killer of Sheep and its enduring legacy as a touchstone for Black filmmakers this last half century.

Rounding out this well-stocked set are a brief cast reunion, filmed amid the 2007 re-release, fresh interviews with Burnett and lead actor Henry Gayle Sanders, Jacqueline Stewart’s chat with Burnett on the 2010 UCLA L.A. Rebellion Oral History Project, and a lovely booklet essay by critic Danielle Amir Jackson that expertly grounds the film in its historical element.

Overall

Few American films touch the rarified air that Killer of Sheep breathes, and Criterion’s UHD restoration is without question the home video release of the year thus far.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.