Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice opens with a family having a barbecue on their luxurious estate, as patriarch Young Man-su (Lee Byung-hun) claims that he’s “got it all.” Immediately you notice how the sky is perfectly blue and how the yard is too well-manicured. Right down to Man-su’s dogs, who are cheekily named after his children, everything within Park’s images is meticulously composed as the family smashes together in a group hug.

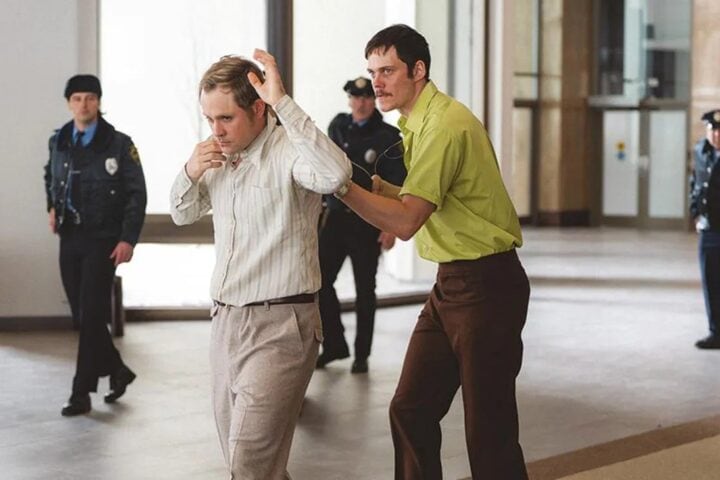

This postcard-perfect paradise is disrupted when Young is laid off from his managerial job at the paper company where he’s worked for 25 years. Young is initially a staunch advocate for everyone on his team who was also laid off, but after months of unemployment and doing menial labor, he’s only out for himself. Trying to land a job in his sector, he sets his sights on a position at Moon Paper, and stoops to violent measures to secure it.

The film was adapted by Park, Lee Kyoung-mi, Don McKellar, and Jahye Lee from Donald E. Westlake’s 1997 novel The Ax, a title that works as a double entendre for both the main character’s firing and his violence. Park’s title change speaks to the farcical approach that defines his film, across which “no other choice” becomes a kind of disingenuous mantra, demonstrating how platitudes and apathy reinforce a violent status quo.

Early on, the Americans who lay off Man-su nonchalantly claim that they had “no other choice,” which is the same sentiment that his potential new employers echo when rationalizing the need to replace more of their personnel with artificial intelligence. At one point, even Man-su says that he has “no other choice” while psyching himself up to commit his violent acts.

Among the film’s ironies is Man-su actually having other choices that don’t involve him killing those competing for a job at Moon Paper. He could sell his massive house and move his family into an apartment. His wife, Miri (Son Ye-jin), could revitalize the career she gave up to have children. They could rely on assistance from Miri’s parents. But the way Young sees it, those options would merely further distance him from the high life that he’s accustomed to.

The film’s sustained farcicality is such that it can keep us emotionally at an arm’s length; one scene in which a disturbing instance of past domestic violence is dredged up ventures into slapstick comedy. Which isn’t to say that No Other Choice is impersonal.

Every step of the way, we’re reminded of how Man-su is failing his family—be it through his paranoia about Miri cheating on him, or through his stepson, Si-one (Kim Woo-seung), learning the wrong lessons and stealing phones for his family. It’s telling of Park’s efforts to keep this caper grounded in personal stakes that Man-su’s eventual relapse on alcohol feels like he’s crossing a bigger moral line than when he stoops to murder.

Among the tragedies and indignities that No Other Choice confronts is the shift from analog to digital—a perhaps ironic fixation given Park’s embrace of digital filmmaking, which makes possible some pretty elaborate, and admittedly impressive, camera trickery throughout the film. Man-su and his peers cling to paper like so many directors to celluloid, feeling that they must use it for fear that no one else will. It’s a correlation that’s underscored by the film’s closing montage, which intersplices the credits with a series of deforestation shots.

Here’s another irony: Paper and celluloid both have a considerable environmental impact. But neither holds a candle to A.I., which in a way is the ultimate villain of the film: environmentally catastrophic, actively dehumanizing, and oh so good for profit margins.

A.I. is the only logical endpoint for the system that turns the laid-off into cannibalistic rats. Learning that his entire workforce has been replaced with A.I., Man-su asks, “You’ll always need one man, right?” What he’s saying is that he will be that man, and by any means necessary. So long as there are people like Man-su, who becomes a symbol of capitalist competition and exclusion at its most extreme, the system will continue to churn. Which reveals No Other Choice less as a tragedy about one man and his family than it is about the state of the world.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

Of course, under capitalism, bosses do have no other choice than to treat workers as disposable units. Corporations have a legal duty to their shareholders to place profits first and everything else last – or, really, nowhere. Any profit-seeking business that places other duties – such as caring about the natural world, or the welfare of workers – too highly will soon find itself out of business.