It would be nice to call Take Me Out a historical artifact, a relic of a time when it seemed earth-shaking that a Major League Baseball star would come out as gay like the play’s hero, the biracial center fielder Darren Lemming does. And yet, in the intervening two decades since Take Me Out premiered in 2002 at the Public Theater, the moment that playwright Richard Greenberg imagined hasn’t manifested. Three openly gay players have joined the minor leagues, but not one major leaguer has come out before retirement. Ever.

Like this season’s revival of Trouble in Mind, Alice Childress’s 1955 play about racial representation in Broadway theater, Take Me Out startles in its immediacy, the sense that much of it could have been written right now. In this case, the tragic timeliness and timelessness doesn’t make up for the play’s scrawniness: Despite director Scott Ellis’s sharp, smooth staging and an affecting, effective team of performers, the story itself registers as contrived and hokey, veering between daffy humor and implausible melodrama.

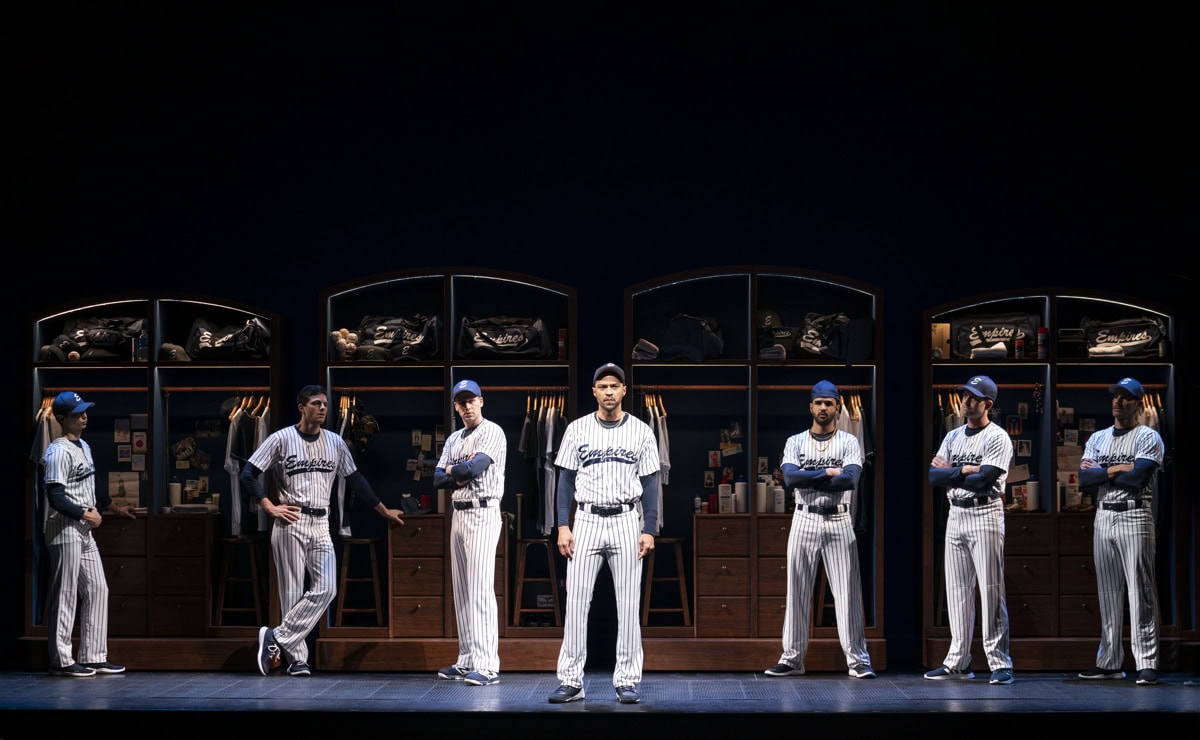

Scrawny, of course, is not part of the play’s corporeal vocabulary. Take Me Out has been best remembered for its nude locker room and shower scenes, and its popularity remains rooted in that sensationalism. (Audience members must lock their phones in magnetic pouches to prevent anyone leaving the theater with documentary evidence.) And while the conversations that take place in the buff reference how the players now view their teammates’ bodies suspiciously and self-consciously through the lens of their rancidly fragile masculinity after Darren’s (Jesse Williams) announcement, there’s nothing particularly progressive or challenging in the way these sequences ask audiences to look at the players’ bareness.

The nudity might seem more necessary if it didn’t require so much justifying narration. Forget “show, don’t tell,” as Take Me Out is all show and tell: “We’ve lost a kind of paradise,” Kippy (Patrick J. Adams) explicates to his teammates mid-shower. “We see that we are naked.”

The play begins in the wake of Darren’s seismic coming-out press conference. He’s a big enough star with a big enough ego to feel confident that his career and Derek Jeter-ish place at the top of the food chain will remain intact. Less certain is how our protagonist’s newly defined sexuality will play out in the locker room, especially once Shane Mungitt (Michael Oberholtzer), a stunning new pitcher with a tragic backstory and a baldly racist and homophobic vocabulary, joins the team (the fictional New York Empires).

The biggest hole in Greenberg’s script is that, with the exception of Darren, his bullpen pal Kippy, and a Japanese pitcher (Julian Cihi) who pretends not to speak English, all of the Empires are, to put it gently, numbskulls. Take Me Out takes such great pains to mock so many of its characters’ interchangeably outlandish stupidity—one insists that the Greeks built the pyramids—that their views on sexuality don’t seem to merit close study: If they weren’t worth taking seriously before Darren came out, why listen to them now? (The spoofy treatment of the Spanish-speaking ballplayers also feels queasily reductive.)

So, with most of the characters positioned as doofuses, the play coalesces around Darren’s bemused acquaintance with new money manager Mason Marzac (Jesse Tyler Ferguson), a gay man who’s new to the world of baseball, and his friendship with Kippy. Ferguson sweetly conveys Mason’s determination to find fellowship with Darren through their shared ostracization: “I don’t really have a community,” Mason admits, “or maybe the community won’t have me.” Take Me Out is clearest and most focused in Mason’s monologues tracing his growing obsession with the national pastime: “Baseball is a perfect metaphor for hope in a Democratic society,” he explains to the audience with the glow of a man freshly in love.

Darren and Kippy, meanwhile, seem close, even if Darren frames his friend’s jocular acceptance of Darren’s sexuality as self-indulgent: After Kippy describes his vision of inviting Darren and his future boyfriend over for dinner with the family, Darren mocks this fantasy as “kind of a Hallmark card with sodomy.” But the slow discovery that what they have most in common is the ballgame—Kippy envies Darren’s closeness with the Black star (Brandon J. Dirden) of a rival baseball team—begins to erode their amity.

Despite their differences, Kippy dominates the storytelling as an almost-omniscient narrator, and Adams radiates with a warm non-specificity, an appealing Nick Carraway to Darren’s more distinctly enigmatic Jay Gatsby. Throughout the play, Darren rarely opens up to anyone, and it’s one of Greenberg’s triumphs of characterization that coming out seems to have so small an impact on Darren’s transparency because he’s still hiding so much of who he is and what he wants. Williams blithely captures the easygoing narcissism—“God made me God,” Darren claims in an act of self-worship that seems to roll off the tongue—and his coy half-smile on the cusp of boredom as fans gush at him is particularly endearing.

But Williams can’t seize power in a play that seems determined to let other characters (white men, as it happens) serve as our conduit to Darren’s consciousness. Dramas like Tarell Alvin McCraney’s Choir Boy have examined Black queerness in fiercely heterosexual spaces with more expressive, autonomous protagonists in the years since Take Me Out first appeared. Greenberg’s play entered the discourse on the intersection of race and sexuality in baseball—a discourse that, 20 years later, has yet to begin in earnest. Suavely performed, this new production doesn’t add all that much substance to the conversation.

Take Me Out is now running at the Second Stage Theater.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.