Sergei Loznitsa’s Two Prosecutors establishes its deadpan absurdism in an opening scene that almost immediately sums up the film’s thesis. In 1937, an elderly, frail-looking man (Ivgeny Terletsky) is manhandled into a Soviet jail on a charge of “antisocial behavior” that even his mirthful jailers don’t seem to understand. He’s quickly put to work reading stacks of appeal letters filed by other prisoners accused of “counter-revolutionary” crimes, the majority of which he tosses into an incinerator after a few seconds’ consideration, at most.

That the film, a satiric look at Stalinism and bureaucracy with shades of Kafka, Orwell, and Gogol, so clearly telegraphs its view of the revolution eating its own right off the bat is, of course, part of Loznitsa’s twisted joke. As in the Ukrainian director’s 2019 documentary State Funeral—a two-hour-plus compilation of archival footage of anonymous masses’ wordless, mechanical marching and weeping at Joseph Stalin’s decadent government-arranged funeral procession—a certain mind-numbing circularity is an essential part of the film’s point.

Adapted from a novella by former Soviet political prisoner Georgy Demidov, Two Prosecutors isn’t quite so conceptual. Kornev (Alexandr Kuznetsov) is a young state prosecutor who’s eager to uphold the Bolshevik ideal of justice. As he investigates the circumstances around the imprisonment and torture of Stepniak (Aleksandr Filippenko), an old Bolshevik worker who was part of the 1917 uprising, by the secret police on charges of disloyalty, and eventually petitions on the prisoner’s behalf, one quickly detects a problem for Kornev: He actually believes that his job as state prosecutor is about enforcing justice, and not simply about prosecuting.

In Stalin’s Soviet Union, questions about the efficacy or justice of the communist system aren’t welcome, and are in fact to be treated with dire suspicion. That our patriotic lawyer nonetheless insists on asking them is to the consternation of scowling foot soldiers and institutional superiors he encounters; the latter are by and large punch-clock cronies who approach their duties with a glib nihilism that’s lost on the self-serious Kornev. The governor (Vytautas Kaniušonis) at his client’s prison, for instance, lounges on an office sofa wheezing with laughter at his own jokes while his prisoners, concealed from the outside world, write letters in their own blood. A recurring gag involves Kornev being made to spend all day in waiting rooms by passive-aggressive superiors trying to nudge him off. He waits, politely, every time.

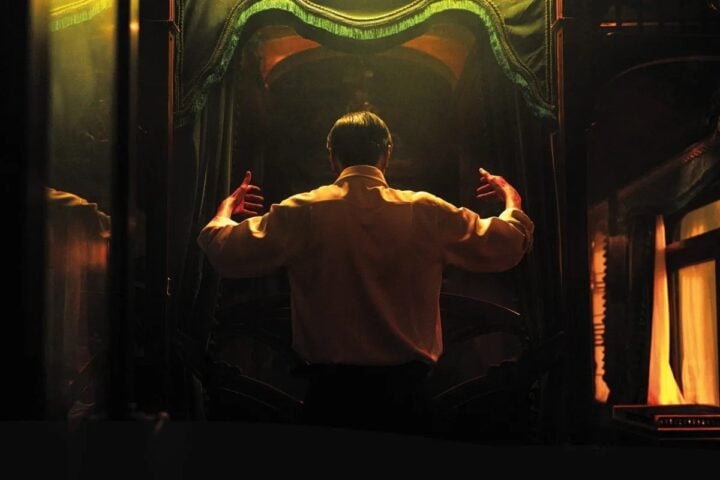

Many films have pitted a justice-loving individual against a corrupt institution. What distinguishes Two Prosecutors, for better and for worse, is the Sisyphean futility it presents along every step of the way. Its frigid color palette, claustrophobic compositions, and painstaking long takes place the audience at an ironic remove from its naïve protagonist even before he’s explicitly and repeatedly warned of the dangers of sticking his neck out.

The cinema-literate, as well as those with a working knowledge of history, will know where this story is going. But the agony—and, given the film’s morbid humor, perverse pleasure—of watching it get there lies in the lacerating level of detail with which Loznitsa captures every single link in the chain of circular logic that binds broken institutions.

Every individual representative of the Soviet justice system redirects Kornev’s concerns to another representative (often across excessively long travel distances and back again), all of them empty suits: Conscientious men like Kornev are in short supply, because the institutional structure favors cronyism over competence and the appearance of efficacy over actual efficacy. Thus the state must arrest innocents, and they must be treated as cruelly as possible, and to question the justice of the state must be unthinkable, because the alternative would be to undermine the state’s appearance of relentless efficacy and ideological purity.

To Americans in 2025, Loznitsa’s explicit warnings about an authoritarian government silencing dissidents and stacking its public institutions with regime-pandering clowns will hardly feel alien. But there’s a deeper resonance to this theme, and it recalls the television work of David Simon and the theoretical writings of Mark Fisher. Those modern Western writers have argued that neoliberalism, with its emphasis on statistics, savings, and the appearance of efficiency as singular measures of institutional value, has ironically created hostile bureaucracies comparable to its communist inverse as facts of Western public life.

Two Prosecutors is about the attempt to free a political prisoner, but even without the omnipresent busts of Stalin, Lenin, and Marx observing its sordid affairs, many of the same story beats would apply, perhaps with less lethal stakes, if the film were about Kornev trying to, say, file an insurance claim. In that sense, America’s current authoritarian nightmare could be imagined as the logical endpoint for institutional decay stretching back decades. The dissection of broken institutions of the past is a valuable exercise in imagining new ones. What Loznitsa’s overpowering fatalism may lack as dynamic drama, it certainly delivers as critique.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.