In Resurrection, a pastiche of pastiches, Chinese filmmaker Bi Gan completely foregoes the earthy magical realism of his remarkable breakout feature, Kaili Blues, for a meta-cinematic exercise near-totally abstracted from reality. He seems aware of it too, as literal vampirism is one of many confounding motifs to emerge in this surreal ode to cinematic undeath.

The film consists of a sci-fi framing narrative and five vignettes meant to correspond, respectively, to five eras in cinema, five critical periods in 20th-century Chinese history, and the five senses. In an opening homage to silent cinema, title cards lay out a dystopian scenario where, in the future, humanity has discovered that the secret to eternal life lies in no longer dreaming. Those who defy the anti-dreaming dictates, known as “Fantasmers,” risk turning into hunchbacked monsters strung out on memories and illusions. Thus, specialized hunters, known as “Big Others,” who are able to enter dreams are dispatched to neutralize them (shades of Paprika and Blade Runner). Cinema also happens to be a medium for dreaming, we’re told, so the process of observing and chasing the Fantasmers looks like watching old movies.

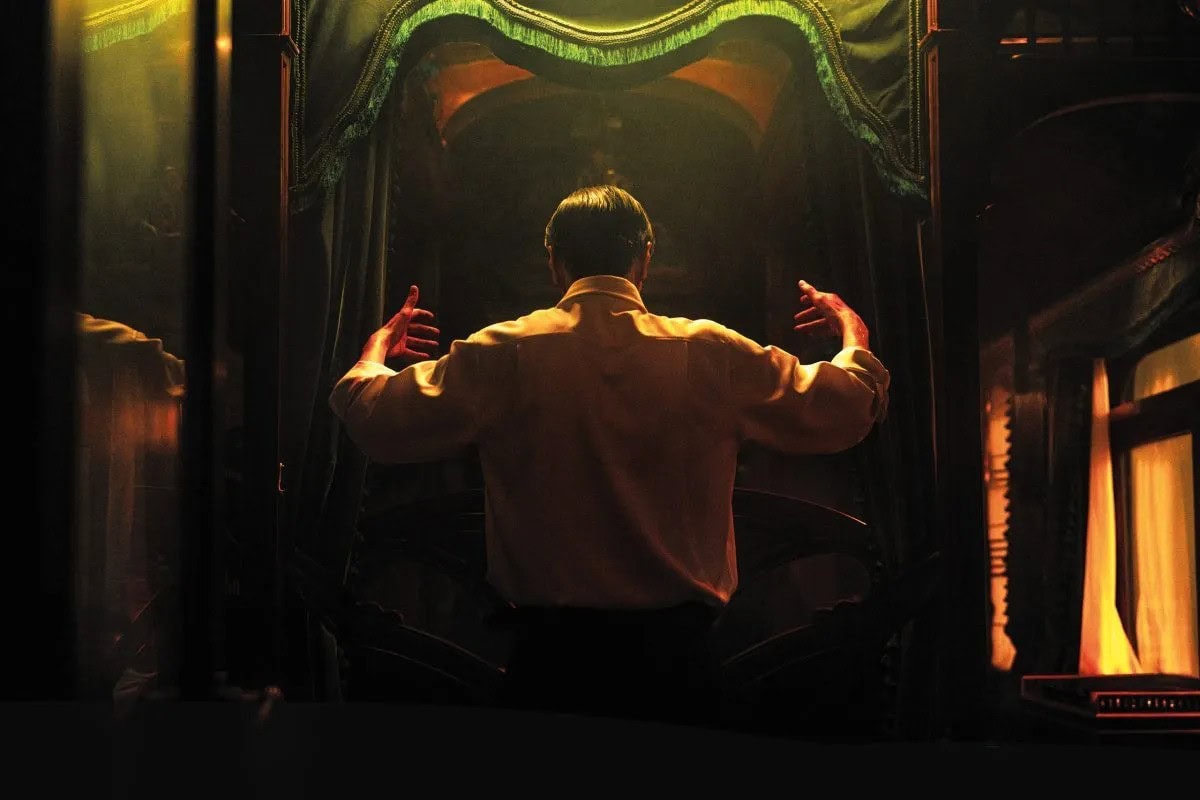

Despite the intertitles’ wordy and less than fully coherent exposition, the opening segment at least seems to establish a fresh visual and narrative direction for Bi’s theme-park-attraction-style set pieces. In an early-20th-century opium den constructed like the set of a German expressionist film and littered with references to silent cinema—the shadows of F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, the curling walls of Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the moon from Georges Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon—one Big Other (Shu Qi) pursues a Fantasmer (Jackson Yee) in monstrous corpselike makeup like a goddess able to alter filmic reality at will.

Moving at a different framerate than the rest of the image, the Big Other is able to approach and talk to the figures in the silent film dream world as easily as she can insert her giant hand into the frame, like a Terry Gilliam animation, to adjust the objects on the stage. After inviting the hobbling Fantasmer to behold himself in a mirror inside her own eye, the titles inform us that the Big Other has taken a shine to this pitiful figure. The Big Other then opens the Fantasmer’s head to find a film projector inside, into which she loads a new reel.

From here, the frame narrative takes a backseat to the rest of the film, as variously hued and considerably less playful episodes pass by with protagonists who, apart from all being ill-fated saps portrayed by Yee, have little apparent continuity between them. A noir thriller set in the ’40s during the Japanese occupation of China involves the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, a magic suitcase, and an extended homage to Orson Welles’s The Lady from Shanghai. A parable set in a Buddhist temple pillaged during the Cultural Revolution sees a man pranked by a mercurial spirit (Chen Yongzhong). A caper set in the post-Dengist ’90s builds a Paper Moon-like odd couple dynamic between a money-hungry grifter and a precocious child (Guo Mucheng). And, finally, a bloody Y2K gangster romance, told in a mammoth tracking shot, is packed with references to Bi’s previous film, Long Day’s Journey into Night.

In terms of narrative, the segments are garbled, with dialogue consisting largely of koans, riddles, and non sequiturs. Most of them end inconclusively or nonsensically. Characters die and come back to life, perform gruesome acts of self-mutilation for poorly articulated reasons, and abruptly reveal themselves to have supernatural powers. At times, Resurrection seems to outright taunt viewers for trying to make sense of it all—one of Yee’s multiple brooding hoodlums declares riddle-solving to be a stupid pastime—and a general theme persists of the sentimental irrationality of art, religion, and romance under attack by cold, modern forces.

In following what he insists is the logic of dreams down a rabbit hole of dazzling technical showcases, Bi’s vocabulary of quotations-within-quotations from endless films and texts smothers the emotional immediacy of the subconscious that animates so many of his inspirations, from Murnau and Welles to Lynch and Wong. His characters are archetypes, ideas of characters amalgamated from a lifelong diet of movies, and he makes little effort to develop any of them psychologically in between all the abstruse philosophizing, spurious exposition, and aggressive symbolism (melting candles and mirrors abound) that take the place of linear drama.

We never find out, for one, why Shu’s Big Other is so fascinated by Yee’s Fantasmer as to follow him through all those dreams in an effort at redemption. A narrator simply informs us that this is so, with the huntress ending up off screen for the majority of the film. We never get much sense of Yee’s character either, since it’s essentially five different ones, each sparsely defined.

The eventual thesis arrived at after nearly two and a half hours—that the movies are magic!—seems trite for how punishing and obscure Resurrection is about getting there. As Bi’s production resources continue to grow larger and his images more baroque with each new work, his attachment to humanity seems to shrink, leading to an oddly cold and academic conception of cinema-as-dreaming that calls more attention to the filmmaker’s whiz-kid technical abilities than the world of untamed emotion insistently described by his characters.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.