Oksana Karpovych’s Intercepted is a chilly but significant document of war. It aims to psychoanalyze imperial violence by juxtaposing haunting, desaturated, depersonalized landscape and interior photography of physical damage wrought by the Russian invasion of Ukraine—and life persisting in its wake—with allegedly intercepted audio of phone calls by Russian men on the front to their mothers, wives, and sisters back home.

Some men we hear question the war and the Russian government only for the women to parrot state propaganda narratives justifying the invasion (such as the West giving Russia no choice, the purported Nazification of Ukraine, or conspiracy theories about American nuclear sites and biolabs) as correction or encouragement. But in other conversations, the roles are reversed, with the men falling back on state narratives to justify their actions. Several confess to war crimes—looting, rape, killing of civilians, torture and execution of prisoners—and the women’s responses range from shocked and horrified to the chillingly supportive.

Throughout the film, we hear Ukrainians dehumanized ethnically (as “khokhols”), economically (as “pigs” suckling off the teat of the West), sexually (as “faggots”), and ideologically (as “Banderites,” “Nazis,” and “fascists”). The Soviet relic of ideological invective is, in some ways, the most chilling for its subtlety: the invocation of hated beliefs, and their ascription to broad national and ethnic groups, as moral permission to dehumanize and kill, in a mixture that destabilizes Anglosphere perceptions of left-right political alignment.

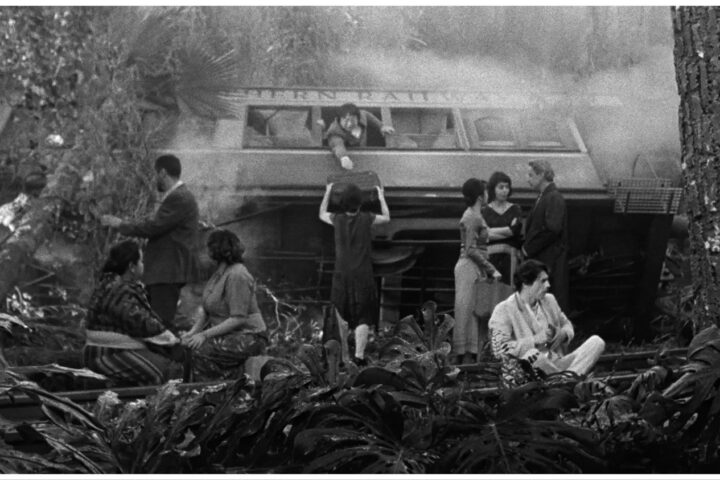

Ukrainians are seen but not heard in Karpovych’s film. Military and civilian, young and old, they trickle about the periphery of the frame among blasted residential buildings and country roads. Atrocities are described graphically by their perpetrators, but no blood or bodies are ever shown—only the now-empty spaces where combat and killing took place. The film’s images and words are an imprint of tremendous state violence but not the violence itself.

The combination of NFNR’s ghostly electronic score and the overall focus on the perpetrators of violence results in an eerie sense of incompleteness reminiscent of Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest. But where Glazer constructed artificial images over his imagined version of a world-historic architect of atrocity, Karpovych looks to wring truth out of authentic found objects depicting the truly ordinary functionaries and victims of the razing.

Karpovych clearly intends to evoke our disgust at the Russian women encouraging their men. But regardless of the political content of their remarks, the anatomy of their emotional responses to loved ones in extreme situations aren’t peculiarly Russian nor ideologically outstanding. One could imagine similar frontline-homefront dialogues, including dehumanization of the enemy as encouragement and catharsis, coming from many sides in many wars past and present. Likewise, Karpovych’s investigations offer little insight into why the average Russian soldier fights in Ukraine that isn’t obvious to even cursory observers of the conflict, and the film merely illustrates the obvious at exhausting length in this regard.

Karpovych and the film’s press materials cite the “banality of evil” and insinuate comparisons between Russian war crimes and the Holocaust, but the national mythology fueling Russia’s assault on Ukraine is simply not as arcane in its exterminatory impulses as Nazism. Where Hitler was a true believer in his own perverse fictions of racial and national identity and inspired true belief in kind, Vladimir Putin’s cruelty is of a more common opportunism.

While ordinary citizens may be the state’s willing agents of warfare, there’s no real question that moral responsibility lies with the ruling class that manipulated them and sent them to fight: As one soldier ruefully observes, “Putin cares about the land, not the people.” In this respect, the film’s most effective material comes in its analysis of how the military state’s permission structures for inhumanity traumatize citizens in order to harden them and focus their hatred.

In the film’s most chilling sequence, one man describes to his mother, half-laughingly, half-tearfully, a particularly appalling form of torture nicknamed “the 21 roses.” (The “21 roses” are 10 fingers, 10 toes, and the penis—made to “bloom.”) First he describes it passively, as something he witnessed from FSB superiors. Then he admits to participating himself, and to enjoying it. Finally he repeats to his mother, for clarity, that he truly enjoyed it, only to remind his mother and himself that the enemy would do the same to him. (Karpovych, seemingly to challenge this assertion, includes a few placid scenes of Russian POWs being fed and clothed later in the film.) It’s the most stomach-churning capsule illustration of learned cruelty as an ideological baptism, the most horrific psychological weapon of the authoritarian impulse as it expands itself by the darkest, most torturous thoughts of its constituents and victims.

Though she avoids any kind of conventional dramatization—all human figures, whether seen or heard, are anonymous, and they hardly ever appear in center frame—Karpovych makes no secret of her stance on the war. Her selection of Russian accounts from 2022 depicts a demoralized army, while the Ukrainian flag and national colors are nearly omnipresent in the scenery, portraying a national resistance that the audience is meant to believe is too deeply rooted and stubborn to be conquered. A concluding intertitle directly condemns Russia’s “imperialist violence” and praises the Ukrainian resistance. Manipulative it may be, but the post-apocalyptic imagery of men and dogs strolling casually by ruined apartments or scrounging in rusty decapitated tanks is a poetic snapshot of uncertainty, tinged by hope.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.