“You see, I’m just Marshall Mathers/I’m just a regular guy, I don’t know why all the fuss about me/Nobody ever gave a fuck before, all they did was doubt me/Now everybody wanna run they mouth and try to take shots at me.” These lines, which make up the chorus of “Marshall Mathers,” sung by Marshall Mathers on the 11th track of The Marshall Mathers LP, serve as the key to understanding the album. It’s the song that perfectly encapsulates its overall ethos. Marshall Mathers is just a normal guy—or at least he thinks so. All the hubbub surrounding him baffles him. These people never cared about him before, but now, for some reason, they do. How dare they.

This anger proves any critique wrong, perceived by the rapper as righteous throughout The Marshall Mathers LP. It drips off every carefully lobbed insult, each perfectly punctuated punch-down, and all the murders, shootings, muggings, and rapes that unfold. But Marshall Mathers, the everyday white dude from Detroit who was saved from the brink of destitution by Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine, would probably describe it as either upholding his honor, defending his character, or getting even with those took the first shot. From the way he tells it, he’s never the instigator; in fact, if you took him at his word, he might just be the most persecuted person in history.

Everyone is out to get Marshall Mathers: his “fuckin’ bitch mom,” who sued him for “10 million”; the conniving Christina Aguilera, who “earned” her verbal tirade after making an offhand quip about his less-than-stellar dating record; the “fuckin’ critics” who he mockingly promised he “wouldn’t say ‘fuckin’ for six minutes”; even his own label, represented by Interscope’s Steve Berman, who tells Eminem on a skit, “You’re rapping about homosexuals and Vicodin…I can’t sell this shit!” Nobody seems to be on his side, save for the ever-loyal Dr. Dre and a rotating cast of horrorcore and hardcore acts (RBX, Sticky Fingaz, and his D12 lackey Bizarre).

In response to the unrelenting attacks against him, Eminem is quick to snap back—or sometimes, he snaps simply for the sake of it, which he does far more often than his underdog image lets on. He takes repeated, gratuitous shots at Christopher Reeve and NSYNC, calls Britney Spears “retarded” for no discernible reason, and revels in homophobia at nearly every turn. Or maybe I’m “heterophobic,” which he accuses his critics of being on the deliriously unhinged “Criminal,” for taking offense to any of this.

Eminem can be scathing, funny, and mean—sometimes all three at once—delivering what feels like an effortless torrent of words and syllables, each landing with near-mathematical precision atop the meticulously polished production of Dr. Dre, the Bass Brothers, and Em himself, who from the outset had a heavy hand in shaping his own sound. In the introduction to the sorta-autobiography, sorta-lyric book Angry Blonde from 2000, he calls himself his own harshest critic, noting that with more resources at his disposal during the making of The Marshall Mathers LP, he pushed himself further than ever before as an artist.

Tellingly, Eminem begins nearly every chapter of the book by mentioning, with some slight variation, that he was in a “fucked up place” when writing any given song from his first two albums. The Slim Shady LP is no slouch, but its follow-up is another beast entirely in terms of scope and ambition: The radio hits hit harder (“The Real Slim Shady”), the storytelling expands beyond the merely personal (“Stan”), and the rapping is sharper—like on “The Way I Am,” where Em spits out each syllable as if his voice were its own percussion instrument.

But the album is also unbearably miserabilist—cruel, abrasive, and disturbing for its own twisted sake. On the war-ready “Amityville,” Eminem paints his hometown of Detroit as a kind of hell on Earth, snarling, “We don’t do drive-bys, we park in front of houses and shoot/And when the police come, we fuckin’ shoot it out with ‘em too.” He engages in a grotesque “drug-off” with the rest of D12 on the sneering “Under the Influence,” including Bizarre, who “jokes” about getting high, having sex with his dog, and then paying for its abortion.

Then there’s “Kim,” a prequel to 1997’s “’97 Bonnie & Clyde,” in which Eminem drunkenly rants at his ex-wife, Kimberly Anne Scott, for six theatrical minutes before chasing her into the woods and stabbing her to death. The song isn’t an endorsement of domestic violence; if anything, I was struck while relistening to the album for this piece at how unabashedly Em is willing to portray himself as a pathetically blubbering, unhinged man-child, but it’s still not something I’d willingly revisit outside the context of listening to the album straight through.

Indeed, The Marshall Mathers LP is a body of work that’s more impressive than it is enjoyable. The technical wizardry is undeniable, but to what end? As a forum for Eminem to rail against middle-American parents blaming him for their children’s woes? To vent about his fractured family? To extol his own insecurities and neuroses? It’s all so dark and morbid—far more so than its predecessor, and less varied sonically than 2002’s The Eminem Show.

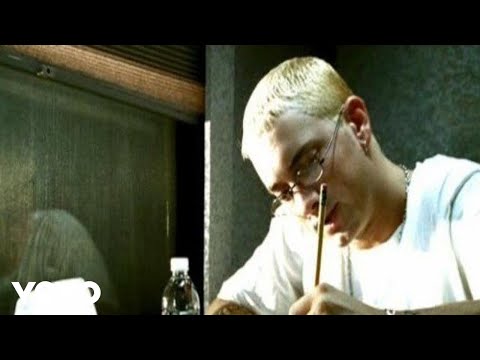

The Marshall Mathers LP’s alternate cover art—with Eminem curled up outside, pill and beer bottles at his feet—has always seemed like a far more accurate microcosm of the world the album inhabits than the standard image of him sitting outside his childhood home. It’s dark and more ghastly. However, both images are in black and white—and as they should be, as color has no place anywhere on an album this soul-crushingly bleak.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.