Hong Sang-soo having but a single film at this year’s New York Film Festival might appear like something of a cinematic recession indicator. While the South Korean auteur has showcased a pair of films at every festival since the pandemic, he brings only What Does That Nature Say to You to this year’s edition. Yet that’s about where the scarcity ends with Film at Lincoln Center’s annual fall celebration of the best in global cinema.

For starters, the festival’s lineup features multiple films by two other directors. Viewed in tandem, Richard Linklater’s Blue Moon and Nouvelle Vague and Radu Jude’s Kontinental ’25 and Dracula make for fascinating explorations of the processes of cultural and artistic production. But the pleasures of this festival extend far beyond the celebration of prolific output.

The biggest theme that stands out from this year’s program is a heightened awareness of colonialism’s long legacy. At the forefront of this crop are With Hasan in Gaza and Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, two documentaries that respectively look at past and present stages of the ongoing conflict between Israelis and Palestinians in Gaza. And while American misdeeds make up the majority of Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s Cover-Up, a documentary portrait of investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, its powerful conclusion bombards us with evidence of the ongoing genocidal activity unfolding in the region.

Elsewhere, Lucrecia Martel’s documentary Landmarks takes the 2009 murder of Indigenous community leader Javier Chocobar as a jumping-off point for a look at the continuing struggle of the Chuschagasta people of Argentina to claim dominion over their ancestral lands. Lav Diaz’s un-romantic epic Magellan, starring Gael García Bernal, is a blistering look at the violence wrought by the Portuguese explorer, while Claire Denis’s The Fence and Pedro Pinho’s I Only Rest in the Storm explore post-colonial dynamics in Western Africa.

Other films at the festival reveal a dynamic range of approaches to similar topics. Mary Bronstein depicts a mother’s life on the edge with frenetic energy in If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, while Milagros Mumenthaler frames that pressure point in The Currents as a study in tightly coiled interiority. Joachim Trier sets Sentimental Value’s tender emotional drama against the backdrop of moviemaking, while Ulrich Köhler takes caustic aim at the industry in Gavagai, which centers on a production of Medea being shot in Senegal. Life-or-death government decisions hinge on the participation of seemingly every moving part in of the American bureaucratic machine in Kathryn Bigelow’s thrilling A House of Dynamite, but such power rests only with the Italian president in Paolo Sorrentino’s contemplative La Grazia.

Few other festivals allow cinephiles to catch up with so many award winners from Cannes, Berlin, and Venice, like Jafar Panahi’s It Was Only an Accident and Jim Jarmusch’s Father Mother Sister Brother, within the same program where they might discover adventurous new voices, namely in the Currents section. No matter their scope or style, what unites the films at the festival is a clearly articulated point of view on a world in a state of turmoil and reinvention.

“Anyone who cares about film knows that it is an art in need of defending, like many of our core values today,” observed Dennis Lim, the festival’s artistic director, on the occasion of the main slate’s announcement. Maintaining more civic-minded values might require some advice from a dissident filmmaker like Panahi, who’s set to appear at the festival for the first time in 25 years. Nonetheless, the 106 films programmed across the five sections of the New York Film Festival at least facilitate making a vigorous case for the vitality of the cinema. Marshall Shaffer

For full reviews of the films in this year’s lineup, click on the links in the capsules below. And for a complete schedule of films, screening times, and ticket information, click here.

After the Hunt (Luca Guadagnino)

Luca Guadagnino’s After the Hunt centers on Alma (Julia Roberts), a Yale philosophy professor who finds herself caught in the middle of a scandal when a student, Maggie (Ayo Edebiri), accuses Alma’s colleague Hank (Andrew Garfield) of sexual assault. Crucial to the film’s desire to challenge right-and-wrong binaries is its elision of both the assault and an off-the-record portion of a meeting between Alma and a dean that leads to Hank’s firing. Instead, the script piles on character details to complicate our views of everyone involved. And while those details are enough for a thoughtful examination of the range of possible responses to sexual assault, there comes a point where the film is defined by its convolutions. Kenji Fujishima

Anemone (Francesco Sossai)

Ronan Day-Lewis’s feature-length directorial debut, Anemone, is ostensibly about brotherhood, but in execution, the story plays out as one man’s unraveling from past traumas in self-imposed confinement. Though anchored by a mercurial performance from Ronan’s father, Daniel Day-Lewis, who also co-wrote it, the film is ultimately unable to tell a family story that lives up to its visual splendor and enigmatic atmosphere. Ronan Day-Lewis, a trained painter, and cinematographer Ben Fordesman dot Anemone with expressionist flourishes; the film abounds in gorgeous and surreal imagery, and at one point Ray comes across a creature with a human face reminiscent of the Night Walker from Princess Mononoke. But as Anemone has all the trappings of a kitchen-sink drama, these fantastical touches feel like they’re trying to distract from the script’s lack of interiority or introspection. Anzhe Zhang

Below the Clouds (Gianfranco Rosi)

“They’re all wrenched from their contexts,” observes an archeologist about a room full of unsorted Neapolitan artifacts that Gianfranco Rosi’s camera surveys in Below the Clouds. That statement could just as easily apply to all the discrete scenes the director assembles into his documentary portrait of the area surrounding Mount Vesuvius, where the local life, like the landscape, feels as if it’s been cut loose from chronological time. While Vesuvius has been dormant since 1944, the legacy of its explosive past in burying Pompeii weighs heavily on those who coexist with the volcano. The ongoing excavations of Pompeii inform this delicate dance with mortality. Similarly, Rosi’s long, languorous, often hushed snapshots of the area between Vesuvius and the Gulf of Naples conjure a sense of life here being suspended in time. Shaffer

BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions (Kahlil Joseph)

BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions, the first feature by multidisciplinary artist Kahlil Joseph, is technically an outgrowth from his video art installation of the same name. Yet its aims feel greater than just adaptation. Joseph has found a means of polyphonous expression for the intellectual point of origin for his artistic exploration: the Encyclopedia Africana, an expansive compendium of African studies edited by renowned scholars Henry Louis Gates and Anthony Appiah. BLKNWS is a vessel for conveying an eye-popping number of entries that merited inclusion in that survey of Black history, culture, and identity—all of which come annotated with their corresponding page number in the tome. But Joseph quickly expands his remit beyond mere fact recitation to embody the project’s spirit of reclamation and revision. Shaffer

Blue Moon (Richard Linklater)

Seven months before Lorenz Hart’s (Ethan Hawke) passing, a single night at Sardi’s led to the devastating realization that both the culture and his collaborators had left him behind. Surrounded by portraits of the industry’s brightest talents, the space becomes like a mausoleum to Hart as he frets about how his legacy will inevitably be flattened like one of the restaurant’s famed line-drawing caricatures. Though he didn’t write Blue Moon’s screenplay, it’s not hard to see what attracted Richard Linklater to the story, given the degree to which it lingers in a specifically bracketed liminal period. Here, that’s when a work passes ownership from the artist to the audience. As the critical reviews roll in over the phone, there’s a steady drumbeat reminding the creators of their tenuous control over the art over which they labor. Shaffer

Cover-Up (Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus)

“All the wrong things are kept secret, and that destroys people,” observed Nan Goldin in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. Now, as if in response to those words, Cover-Up, Laura Poitras’s follow-up to her 2022 documentary, takes us on a journey through the work of investigative journalist Seymour Hersh to reveal how disclosures of major institutional scandals do little to steer America back on track. The foundation of the documentary, which Poitras co-directed with Mark Obenhaus, is Hersh’s recounting of these depressing developments. He uncovers a cancer that infects institutions and inspires individuals to take actions that respond to perverse incentives. “We are a culture of tremendous violence,” Hersh somberly declares, and Cover-Up provides over a half-century’s worth of substantiation for his claim. Shaffer

The Currents (Milagros Mumenthaler)

Milagros Mumenthaler’s The Currents is a film of layered hints. Basic plot details are revealed at a trickle, if at all. Others can only be guessed at. This commitment to vagueness can be frustrating, even self-indulgent at times. But considered as a means of getting across the protagonist’s subjectivity, it comes to feel purposeful. For Lina (Isabel Aimé González-Sola), not only are such details in the background of her life, they’re trivial compared to what’s happening inside her mind. The Currents recalls Lucrecia Martel’s work, in which effects or symptoms may be visible on screen, but their root causes are kept secret. But Mumenthaler’s attention to metaphor and subjectivity also invites comparison to Virginia Woolf’s formalist yet compassionate illumination of characters’ inner landscapes. William Repass

Dracula (Radu Jude)

The central premise of Radu Jude’s Dracula is an emerging director’s (Adonis Tanța) attempt to make an entertaining Dracula film for studio executives by deploying a fictional cutting-edge A.I. system to develop different iterations of the character, each of which are introduced by the director himself in a direct address to the audience. Throughout, Jude’s cheap, smartphone-shot real-world footage is deliberately free of the kind of flat professionalism that a machine plausibly could be trained to imitate. Which isn’t to say that it’s any more pleasant to look at than his gleeful unleashing of A.I. outputs. Is the restless vitality of his slapdash ways intended to illustrate the superiority of human creativity to faceless techno-capitalism, or is he mocking the Luddite defense of art’s purity by presenting something so sloppy? Knowing Jude and his compulsive rejection of all pieties, the answer is likely yes to both questions. David Robb

Dry Leaf (Alexandre Koberidze)

Dry Leaf was shot on a Sony Ericsson phone, one likely from the mid-2000s, which saves its video files with extremely lossy compression, resulting in chunky digital compression artifacts (called DCT blocks) that obscure most of what’s on screen, especially if it’s moving, and especially at night. Since we come across this form of compression so rarely these days, Dry Leaf’s tableaux are impressionistic in ways that recall the plein air landscapes of Claude Monet. But when the figures within the frame move, they resemble the globs of color and lines in a J.M.W. Turner seascape. Alexandre Koberidze’s film is at its most hypnotic during such moments of near-total abstraction, like when the sudsy water applied during car wash dances along during the drying cycle or trees moves in the wind. Koberidze reminds us that not seeing is sometimes a way of seeing the world differently. Zach Lewis

Duse (Pietro Marcello)

The title of Pietro Marcello’s Duse may refer to Eleonora Duse (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi), the great fin de siècle Italian stage actress, but the film isn’t just a portrait of the artist’s life. Duse’s repeated references to creating a new Athens within Italy provide a crucial insight into how she threads a delicate needle for her persistence under fascist rule. But Marcello doesn’t turn Duse into a martyr for her cause. The film avoids revanchist notions similar to those that pervade fascist ideology, even if certain elements of Duse’s struggle may be righteous. Marcello doesn’t dwell on the old at the expense of creating something new. Unlike Duse, who struggles to disprove Sarah Bernhardt’s (Noémie Lvovsky) notions of her art as “like walking into a world where time stopped,” his creativity maintains an undeniably contemporary streak. Shaffer

Father Mother Sister Brother (Jim Jarmusch)

A moody cool defines Jim Jarmusch’s Father Mother Sister Brother, a triptych of tales in the mode of 1991’s Night on Earth and 2004’s Coffee and Cigarettes, though marked by a much more wizened (and wise) melancholy. After the fuck-the-world irascibility of Jarmusch’s 2019 zombie comedy The Dead Don’t Die, this feels like a comparative balm. Those familiar with Jarmusch’s work know what to expect: leisurely rhythms, repeated visual motifs (overhead shots of clinking coffee mugs, most of all), and a hipster connoisseurship that’s as likely to repel as it is to intrigue. More closed-circuit conversations unfold once the kids get to their respective destinations. No one ever wants to say what they’re thinking, and Jarmusch approaches all the halting small talk and willful evasions in varied tones. Keith Uhlich

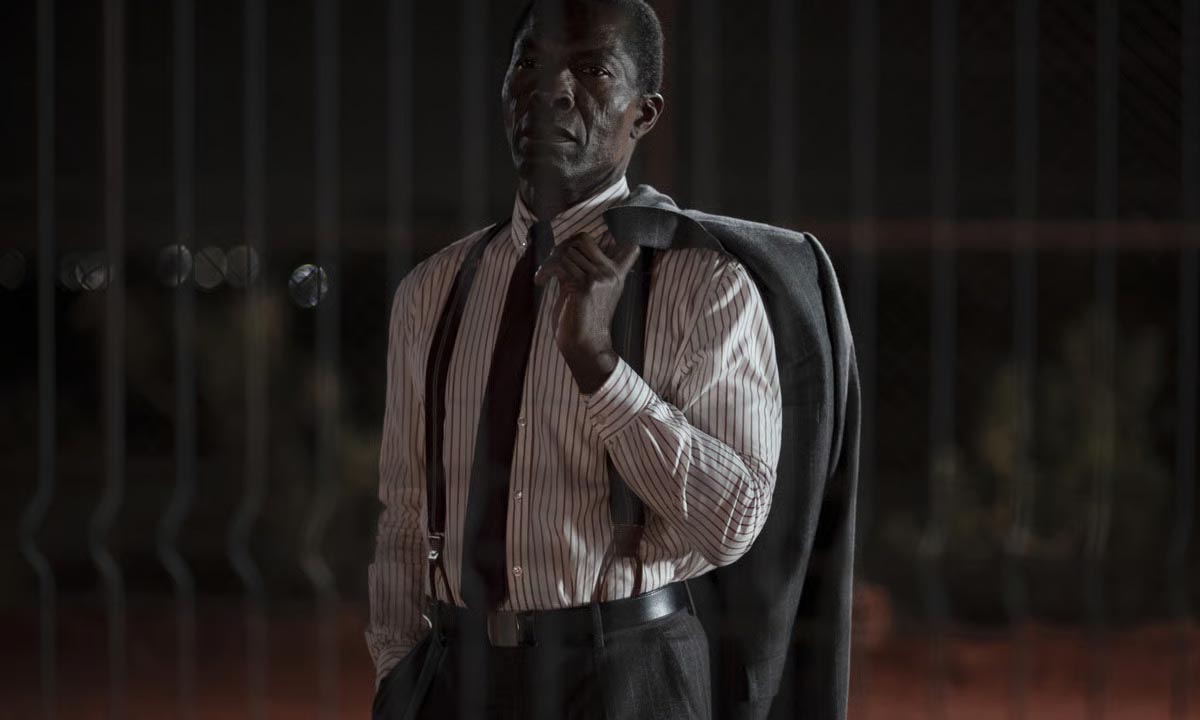

The Fence (Claire Denis)

The play’s not the thing in Claire Denis’s The Fence. A mostly English-language adaptation of Bernard-Marie Koltès’s Black Battles with Dogs, the film dramatizes a tense nighttime standoff on a West African construction site between Horn (Matt Dillon), the white foreman, and Alboury (Isaach De Bankolé), a local demanding the return of his brother’s corpse. Wrapped up in the confrontation is Horn’s wife, Leonie (Mia McKenna-Bruce), newly arrived from overseas and increasingly alienated by her unfamiliar surroundings. Also on hand is Cal (Tom Blyth), Horn’s cocky second-in-command who may have had something to do with the circumstances surrounding that aforementioned dead body. It’s a simple setup, though it’s one that Denis approaches via a discordant melding of cinematic and stagy modes. Uhlich

Gavagai (Ulrich Köhler)

Medea persists in our cultural memory mainly as the embodiment of female vengeance, most remembered for her murder of her unfaithful husband, his new bride, and her own two children in response to her husband’s betrayal. But Euripides’s play is also the story of a stranger in a strange land, castigated by the people of her adopted home of Corinth for her supposed “barbarian” origins. Ulrich Köhler’s Gavagai zeroes in on this element of the text, using a fictional film adaptation of Medea as a locus for a complex treatise on hierarchies of race, gender, and power in the contemporary art world. If Kohler’s 2018 film In My Room is partly about the persistence of social niceties even after the literal end of the world, Gavagai examines how the prejudices we’ve supposedly left in the past still shape that world. Brad Hanford

La Grazia (Paolo Sorrentino)

In La Grazia, writer-director Paolo Sorrentino unassumingly zeroes in on fictional Italian President Mariano De Santis’s (Tony Servillo) creeping sense of despair as the man begins to see the end of his tenure in tandem with the end of his life. It’s a somewhat uncharacteristic approach for Sorrentino, and it affords the various moral crises that De Santis grapples with the space to breathe throughout the film. La Grazia’s biggest strength lies in its ability to express De Santis’s passivity through the motif of the weight of things, from the physical to the spiritual, and while the sheer number of plot threads that Sorrentino weaves into the film’s design can grow fatiguing by the end, this story about disillusionment and contemplation excitingly blooms into one of existential revitalization. Taylor Williams

A House of Dynamite (Ulrich Köhler)

Kathryn Bigelow’s nerve-shredding A House of Dynamite has echoes of Fail-Safe and Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, and it arrives at a time when global tensions are approaching a boiling point unseen since the Cold War’s end. Clearly inspired by Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine—the only present-day conflict explicitly referenced here, albeit in passing—it revolves around an intercontinental ballistic missile launched from somewhere in the Pacific and toward American soil without warning. There’s also no clear aggressor. Like Fail-Safe, A House of Dynamite stares down impossible questions about an unthinkable scenario. But for all of its affectations of ripped-from-the-headlines realism, the film envisions a hyper-competent, ethically concerned American government that feels wildly out of date in 2025. Eli Friedberg

I Only Rest in the Storm (Pedro Pinho)

Sérgio (Sérgio Coragem), the Portuguese protagonist of Pedro Pinho’s didactic I Only Rest in the Storm, goes to Guinea Bissau to write an impact report of a road-building project. There he encounters extraordinary individuals who exist mostly to challenge age-old European prejudices about Africa. I Only Rest in the Storm’s original title is O Riso e a Faca, which translates to The Laughter and the Knife, and it establishes the kind of binarity that reflects the film’s shortcomings, as it never quite goes beyond the pitching of oppositions. This is a film where pedagogy even has to share space with the carnal frisson of the dance floor, with partygoers chatting about the colonial aggression of the Portuguese and resistance to it. Diego Semerene

If I Had Legs I’d Kick You (Mary Bronstein)

“Mommy is stretchable,” claims the daughter of Rose Byrne’s Linda at the outset of Mary Bronstein’s If I Had Legs I’d Kick You. Cinematographer Christopher Messina already captures the actress in a tight close-up from the first frame, and his camera pushes in as close as a single eyeball while she feverishly disputes her child’s characterization. It’s a dynamic established early on for the visual style as well as the narrative: The more Linda protests, the more claustrophobic she becomes. The camera scarcely ever leaves Byrne’s face in an extended prologue that culminates in a ceiling collapsing into Linda’s apartment, flooding it and forcing her to shack up in a dingy motel with her daughter. Once the title card hits, Bronstein never takes her foot off the gas across this tense tale of a mother swirling in a vortex of burnout. Shaffer

Is This Thing On? (Bradley Cooper)

If A Star Is Born and Maestro were self-consciously heavy stories about the damage wrought by adulation, Is This Thing On? finds Bradley Cooper working in a more upbeat vein. Inspired in part by the life of British comic John Bishop, the film seems as if it’s going to take us into the intricate world of standup comedy, but its true focus is on the off-stage relationships, the chaos of family life and friend drama. With this no less personal film, yet one with considerably lower stakes, where art is understood to matter to Alex (Will Arnett) but isn’t framed as everything to him, Cooper gives himself room to indulge in free-wheeling fun. It’s a finely observed and good-natured piece of work that carries some of the creative angst of Cooper’s other films but without the need to convince us of its main character’s genius. Chris Barsanti

It Was Just an Accident (Jafar Panahi)

Across It Was Just an Accident, Jafar Panahi is most interested in exploring how life under tyranny turns everyone into the worst versions of themselves. This and other thematic ingredients are familiar from many of his previous films, and with It Was Just an Accident, he stirs them into a more conventional narrative framework. Which isn’t to say that Panahi’s anti-authoritarian spirit doesn’t flow through the film, as evidenced by his deliberate decision to not have his female characters wear hijabs, in defiance of Iran’s strict religious rules. And It Was Just an Accident’s final moments bring the filmmaker’s critique of contemporary Iran into especially grim focus, as an ostensibly happy conclusion morphs into existential dread with the realization that no matter what the oppressed do to move past the trauma of what they’ve experienced, it will always be one triggering thought, or sound, away. Mark Hanson

Jay Kelly (Noah Baumbach)

Noah Baumbach made his feature debut in 1995 with the acidic postmodern dramedy Kicking and Screaming. Thirty years later, his shrine to the enduring power of movie stars, Jay Kelly, marks the culmination of an artistic evolution. As Baumbach’s later filmography revisits familiar themes with a greater sense of empathy and understanding, this represents the moment when the filmmaker has gone fully soft. Baumbach pays homage to old-fashioned big-screen icons like the eponymous Jay Kelly, a thinly veiled fictionalization of star George Clooney, without running over into adulation. But the film also dips too far into schmaltz. Still, as Baumbach sells the sappiness in Jay Kelly with the same sincerity of his convictions as in his more acerbic works, the film holds together as a lightweight delight. Shaffer

Kontinental ’25 (Radu Jude)

Radu Jude’s Kontinental ’25 is unmistakably his own, evident in everything from self-derisive humor to the surreal interventions in everyday situations. The situation that sets off the film’s plot into motion, where even the most precarious of living conditions of an elderly Romanian rendered destitute by modernity’s toxic seductions can’t be sustained, is fundamental: Out with the old, in with the new. What’s most endearing about Kontinental ’25 are the moments when Jude’s signature as an auteur is made ferociously visible. A suspiciously quotidian situation suddenly cracks the film open, revealing its political engagement not with a professorial or patronizing tone, but with the disarming strategy of the ludicrous. And it’s to remind us of how ridiculous the state of the world is, and how ridiculous we are for accepting it. Semerene

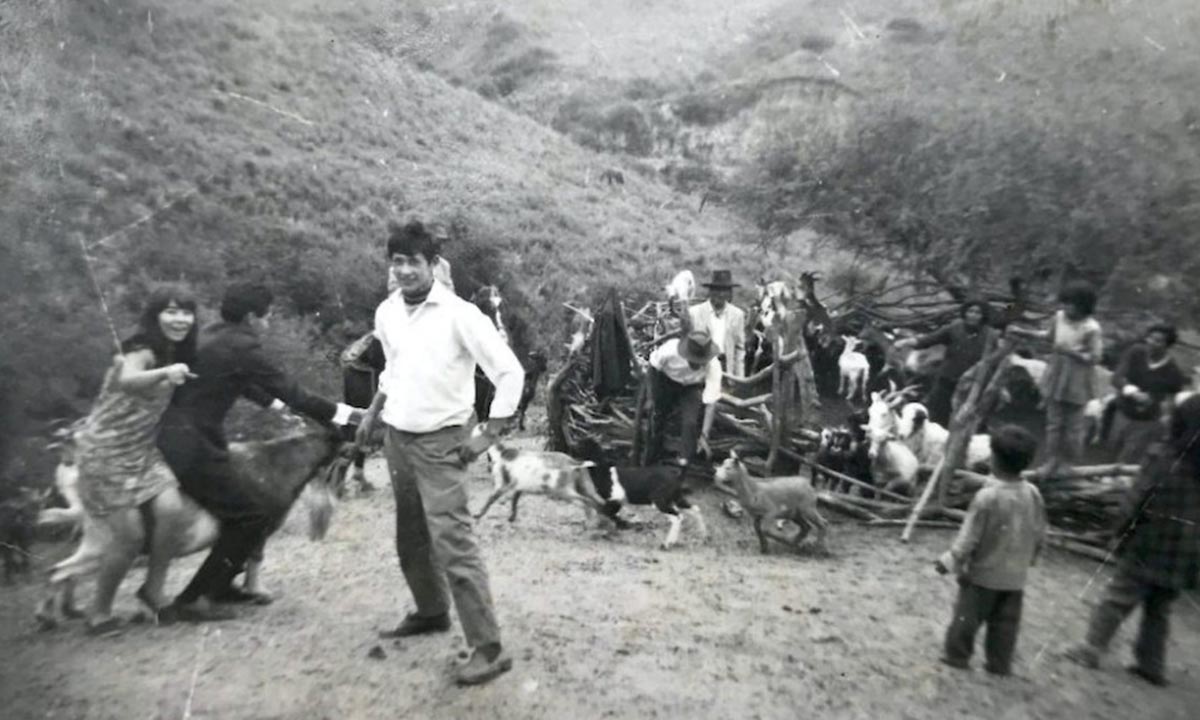

Landmarks (Lucrecia Martel)

Landmarks, Lucrecia Martel’s first feature-length documentary, opens with satellite imagery above the Earth before narrowing the lens’s focus on the Chuschagasta people’s land in Argentina’s northwestern Tucumán Province, stressing its need to witness the totality of a tragedy: The murder of the 68-year-old Chocobar by Darío Luis Amín, a local landowner attempting a forcible eviction to exploit his land’s minerals. The film exists somewhere between a legal drama and an ethnographic portrait of the Chuschagasta community as it strives to maintain dominion over its land. What’s on trial for Martel isn’t merely the actions of Amín and the other accomplices responsible for Chocobar’s death. Landmarks takes up its case against the centuries-old processes of dehumanization and disenfranchisement of a people. Shaffer

The Last One for the Road (Francesco Sossai)

Francesco Sossai’s The Last One for the Road is a grungy love letter to the Veneto region of Italy that feels as if it’s wrenching itself back from the cusp of saying something more profound about the place and the people who inhabit it. Carlobianchi (Sergio Romano) and Doriano (Pierpaolo Capovilla) are two uninhibited, cash-strapped petty criminals who seem to live every moment of their lives in anticipation of their next drink. On their way to surprise their old friend, Genio (Andrea Pennacchi), at the airport, the two fiftysomething men befriend a shy college architecture student, Giulio (Filippo Scotti), and a series of hijinks derails what should have been a short trip into a long journey that touches on but never lingers for very long on the characters’ social realities. The film fully gives itself over to an aimlessness that doesn’t so much reflect the characters’ lives as it does the script’s lack of commitment to interiority. Zhang

Late Fame (Kent Jones)

As a film about the tortured process of artistic creation, Late Fame subverts expectations in one notable respect. Samy Burch’s screenplay sets the stage for a narrative of rebirth upon Ed’s (Willem Dafoe) rediscovery. As a group of well-heeled young creatives prepares for a big public exhibition, it hopes that a reading from the lapsed poet will drive interest around the event. But any prospects of Ed rediscovering his creative spark are quickly dashed, as he finds himself too entrenched in his current routine to reconnect with his former craft. From there, though, any and all tension that that film has built up evaporates. Late Fame manages to coast for a while on Dafoe’s performance, and Kent Jones’s direction is scrupulously sincere, but neither the actor nor the director is aided by a script with a limited perspective on the characters. Shaffer

The Love That Remains (Hlynur Pálmason)

Hlynur Pálmason’s The Love That Remains focuses on a year in the lives of Anna (Saga Garðarsdöttir), Magnús (Sverrir Gudnason), their three children (Ída Mekkin Hlyndsdóttir, þorgils Hlynsson, and Grímur Hlynsson), and their dog Panda on their farm in rural Iceland. Pálmason, who has a background in visual art, explores the family’s dynamics through a vignette-like structure that sometimes feels akin to walking through an art exhibition. That’s not to say he treats his human characters as art objects, just that he puts his trust in the viewer to grasp crucial information based on the snapshots he shows us. What emerges from this patchwork quilt isn’t exactly revelatory, but the film’s character details and freewheeling formal qualities make the narrative feel fresh more often than not. Fujishima

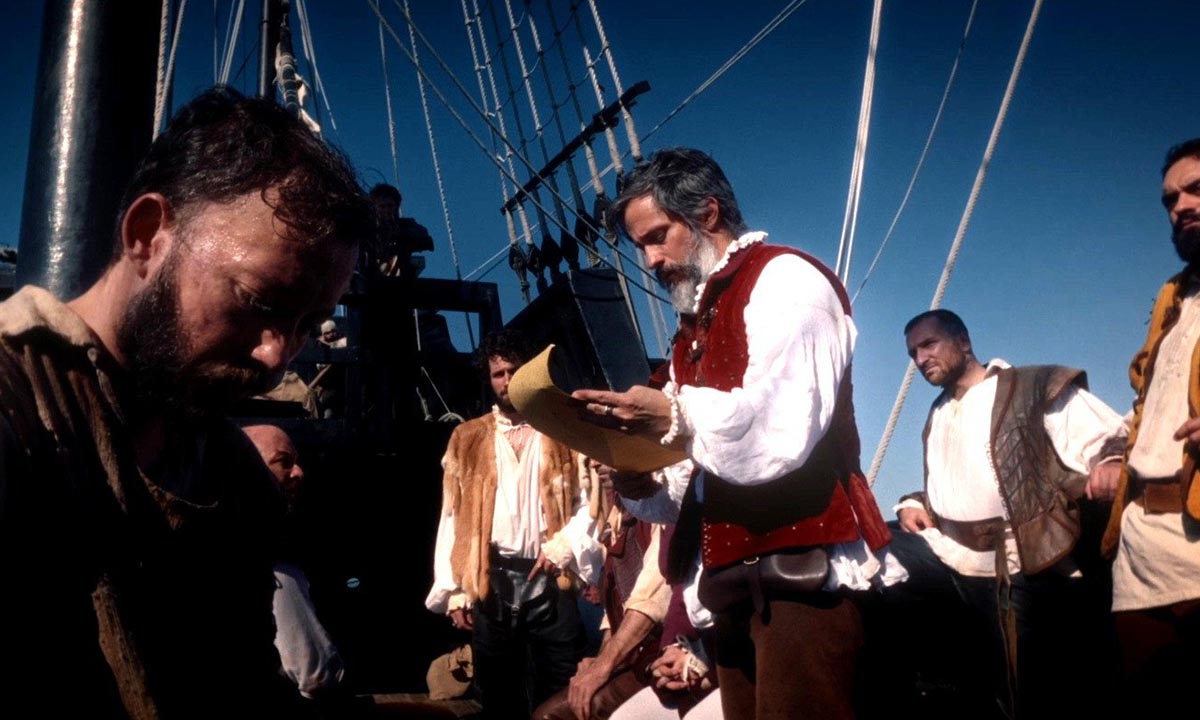

Magellan (Lav Diaz)

Lav Diaz has built his reputation making black-and-white, epic-length portraits of everyday Filipinos, so when his Magellan was announced, it raised eyebrows among his fans. Here is a 160-minute biopic made in color, with an honest-to-God movie star, Gael García Bernal, at its center. But fears that Diaz has surrendered to the conventional are quickly assuaged by the film, which toys with expectations of what a biopic from the filmmaker would look like without turning into a meta-commentary on his work. Fernando Magellan’s journey and his conquest of the Philippines are historical fact, but Diaz’s film suggests a series of medieval tapestries depicting the knight-errant who, in his dragon-like mania, slew and was slain. That such a tale is woven enchantingly only adds to the mythic quality of historical horror at its center. Lewis

The Mastermind (Kelly Reichardt)

The Mastermind marks a new chapter in Kelly Reichardt’s ongoing tapestry of American life through the eyes of its eccentric outsiders, specifically capping off a trilogy about the intersection of art and commerce at differing stages of American capitalism. But where First Cow and Showing Up offer sympathetic portraits of artists striving for personal expression despite adverse material conditions, Reichardt’s script here focuses on the (attempted) exploitation of others’ expression for material gain. There’s more than a hint of envy to J.B.’s (Josh O’Connor) plan, with his desire to possess and profit from art without doing the work of an artist representing another of his characteristic shortcuts. For Reichardt, who struggled to finance a follow-up to her feature debut, 1994’s River of Grass, for a 12-year period that nearly drove her out of filmmaking, the subject feels personal. Hanford

Miroirs No. 3 (Christian Petzold)

Along with many of his contemporaries in Germany’s Berlin School of filmmaking, Christian Petzold has made a career out of allegorizing the soullessness of his country’s neoliberal regime and the fascistic impulses preserved at its core. Petzold has certainly earned a break from diagnosing the ills of modernity, and in many ways his new film, Miroirs No. 3, is just that: a quietly haunting domestic drama that remains cloistered in its pastoral setting, with little to no reference to the world outside. And yet, in the film’s examination of that very desire—to retreat from the world and its complexities, and even oneself by extension—Petzold has crafted yet another sneakily trenchant commentary on How We Live Now. Hanford

No Other Choice (Park Chan-wook)

No Other Choice was adapted from Donald E. Westlake’s novel The Ax, a title that works as a double entendre for both the main character’s firing and his violence. Park Chan-wook’s title change speaks to the farcical approach that defines his biting new film, across which “no other choice” becomes a kind of disingenuous mantra, demonstrating how platitudes and apathy reinforce a violent status quo. Learning that his entire workforce has been replaced with A.I., Young Man-su (Lee Byung-hun) asks, “You’ll always need one man, right?” What he’s saying is that he will be that man, and by any means necessary. So long as there are people like Man-su, who becomes a symbol of capitalist competition and exclusion at its most extreme, the system will continue to churn. Which reveals No Other Choice less as a tragedy about one man and his family than it is about the state of the world. Williams

Nouvelle Vague (Richard Linklater)

Nouvelle Vague charts the production of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, and it’s during the first act where Richard Linklater’s film feels the most like a conventional biopic. There’s an apparent contradiction between the radical spontaneity that Godard chases throughout the making of Breathless and the more conventional narrative approach of Linklater’s film, though spontaneity was perhaps always incompatible with the nature of this project. Still, there’s pleasure to Nouvelle Vague’s winking affection for Breathless, as evidenced by the decision to shoot the film on 35mm black-and-white stock, complete with cigarette burns, and the crackles and pops in the sound, even if that’s not enough to ultimately elevate Nouvelle Vague beyond a pleasantly slight love letter to the French New Wave’s origins. Williams

The Perfect Neighbor (Geeta Gandbhir)

Composed almost entirely of police bodycam and interrogation room CCTV footage, The Perfect Neighbor tries to make sense of a senseless killing that happened in Ocala, Florida, in 2023. At first, Geeta Gandbhir’s documentary plays out like a mystery, as we hear from both sides of a petty neighborhood dispute and try to figure out who’s lying. Since we know from the beginning that this conflict will end in a death, we also spend this time wondering how something so small could possibly have ended so tragically. And then, when the truth emerges, it becomes a powerful statement about the Stand Your Ground laws that have made these tragedies so much more commonplace, and justice afterwards much harder to achieve. Ross McIndoe

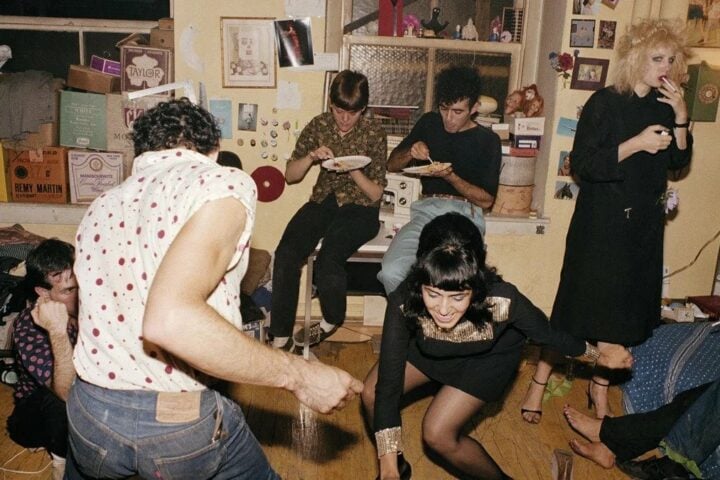

Peter Hujar’s Day (Ira Sachs)

Ira Sachs’s Peter Hujar’s Day simply consists of photographer Peter Hujar (Ben Whishaw) talking about his day and well-connected autofiction writer Linda Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall), gently nudging him along, less as an interviewer and more as a curious friend. Besotted with art and talk, the film has no conflict to speak of or any noteworthy stakes, except for perhaps a certain brooding realization that Hujar would be dead in less than a decade and a half. As much an art historical project as a film, it could just as easily run as a video installation on a constant loop at the Whitney as it could in a theater with soda-sticky floors. And its ability to be at home in both contexts attests not only to the breadth of Sachs’s artistry but also to Hujar’s devotion to exploring the relationship between high and low culture. Barsanti

Resurrection (Bi Gan)

Bi Gan’s Resurrection, a meta-cinematic exercise near-totally abstracted from reality, consists of a sci-fi framing narrative and five vignettes meant to correspond, respectively, to five eras in cinema, five critical periods in 20th-century Chinese history, and the five senses. The eventual thesis arrived at after nearly two and a half hours—that the movies are magic!—seems trite for how punishing and obscure Resurrection is about getting there. As Bi’s production resources continue to grow larger and his images more baroque with each new work, his attachment to humanity seems to shrink, leading to an oddly cold and academic conception of cinema-as-dreaming that calls more attention to the filmmaker’s whiz-kid technical abilities than the world of untamed emotion insistently described by his characters. Friedberg

Romería (Carla Simón)

The title of Carla Simón’s Romería is Spanish for pilgrimage, which points to the complicated nature of Marina’s (Llúcia Garcia) more than just physical journey across the film. Simón’s instinct for sketching in crucial narrative and character detail within a naturalistic context remains as unerring as ever. It’s on a visual level, however, that Romería marks an advance on both Summer 1993 and Simón’s 2022 follow-up, Alcarràs, as exemplified by the moment when, its second half, the film suddenly dives into full-on fantasy. A dramatization of the dark truths Marina has learned about her parents, this sequence is deeply moving not only for its sense of clear-eyed grace and forgiveness, but for the way it evokes the feeling of a budding filmmaker discovering the cathartic power of artistic creation. Fujishima

Rose of Nevada (Mark Jenkin)

Mark Jenkin’s Rose of Nevada combines the seaside community melodrama of Bait with the supernatural overtones of Enys Men to trace the metaphysical fallout from a long-lost fishing boat’s return to the harbor of a village in Cornwall. The film is lensed with a wind-up Bolex camera that allows for limited shot durations of up to 30 seconds, and there’s an aptly ghostly quality to the way each richly textural image gives way to the next in quick, fluid succession. Throughout, Jenkin places primacy on close-ups—of hands, feet, faces, objects, a pesky hole in one character’s roof—that come to suggest puzzle pieces locking together to reveal larger portraits of the film’s working-class setting. Combined with the vintage look of Rose of Nevada, the eerie soundscape adds to the impression that the setting is unstuck in time. Hanson

The Secret Agent (Kleber Mendonça Filho)

Pictures of Ghosts saw Kleber Mendonça Filho reminiscing about the cinemas he frequented as a child and young adult in his coastal hometown of Recife. His latest, The Secret Agent, at first suggests a film from a bygone era, its ’70s-set tale of institutional corruption and surveillance recalling the likes of Three Days of the Condor and The Parallax View. This propulsive thriller, which begins with a title card that cheekily establishes the 1977 setting as “a time of great mischief,” hatches a byzantine plot centered around a widowed ex-tech researcher, Armando (Wagner Moura), who’s been reduced to living in hiding ever since his leftist political sentiments put him on the radar of Brazil’s military dictatorship. More broadly appealing than Mendonça Filho’s past films, The Secret Agent is still unmistakeably the work of an artist who’s deeply fascinated with the ways in which cinema, politics, and personal history co-mingle. Hanson

Sentimental Value (Joachim Trier)

As Nora, a successful stage actor who’s struggling with stage fright and a love life limited to an ongoing fling with a married co-star, Jakob (Anders Danielsen Lie), Renate Reinsve is magnetic in Joachim Trier’s Sentimental Value. She conveys fragile desperation and weary sadness in a refreshingly unaffected way, from an opening scene in which Nora demands Jakob slap her out of an anxiety attack, to her more subdued interactions with family members. Indeed, for all of the film’s intelligent dissection of historical trauma and creativity, its most resonant scene is an intimate heart-to-heart between Nora and her sister (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas), as they reflect on the ways in which their lives have diverged since childhood. Potent in its simplicity and directness, it’s the clearest expression of the film’s emotional core, in which lies a genuine melancholy that Trier’s artisanal compulsions can never fully obscure. Robb

Sirât (Óliver Laxe)

Sirât is named after the mythic Islamic bridge between paradise and hell that an opening text card describes as “thin as a strand of hair and sharp as a sword.” Accordingly, Óliver Laxe’s film proceeds as a contemporary fable whose characters shuttle between extreme polarities, none more so than Luis (Sergi López), who arrives at the scene of a rave in the Moroccan desert—his young son, Esteban (Bruno Núñez Arjona), and their dog Pipa in tow—looking to find his missing daughter. Sirât, whose depiction of transcendence through dance complements its spiritual inspiration, is a vivid meditation on human possibility in the face of fate and nature’s tumultuous might, ending in a fog of ambiguity that mirrors the characters’ bewilderment. This is foremost a film about the power of feeling over understanding, which is sometimes the only antidote to a world that continues to grow more confusing and unstable. Hanson

Sound of Falling (Mascha Schilinski)

Death is a paradox, at once the most familiar part of our world and, per Shakespeare, “the undiscovered country.” Mascha Schilinski’s haunting Sound of Falling, which is set across the entirety of the last century in rural eastern Germany, probes at the inner lives of four girls of different generations who live in close proximity to death—and to each other. Visual and audio motifs tie the worlds of these girls’ together: a hole in the barn door that offers escape or capture, vaguely threatening eels that live in a river, characters who look to the sky and mutter the word “warm” to themselves, photographs that turn the living into ghosts and project the dead into the world of the living. Schilinski’s poetic interweaving of four generations suggests, well, the sound of falling, of the past resonating in the present. Pat Brown

Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere (Scott Cooper)

If you like your rock superstars benignly anguished, Scott Cooper’s Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere has you covered. As Bruce Springsteen, Jeremy Allen White is all slouched posture and distant stares, an achingly sensitive soul at an epochal crossroads. You might say that Bruce has to walk hard through all his unresolved childhood issues with his drunken dad, Dutch (Stephen Graham), though it’s more like a slow shuffle toward several painfully trite revelations. There are plenty of real-life anecdotes that Cooper draws from Warren Zane’s 2023 behind-the-scenes book Deliver Me from Nowhere: The Making of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, but they’re filtered through the hoariest of biopic clichés. Uhlich

Two Prosecutors (Sergei Loznitsa)

Many a film have pitted a justice-loving individual against a corrupt institution. What distinguishes Sergi Loznitsa’s Two Prosecutors, for better and for worse, is the Sisyphean futility it presents along every step of the way. Its frigid color palette, claustrophobic compositions, and painstaking long takes place the audience at an ironic remove from its naïve protagonist even before he’s explicitly and repeatedly warned of the dangers of sticking his neck out. The cinema-literate, as well as those with a working knowledge of history, will know where this story is going. But the agony—and, given the film’s morbid humor, perverse pleasure—of watching it get there lies in the lacerating level of detail with which Loznitsa captures every single link in the chain of circular logic that binds broken institutions. Friedberg

What Does That Nature Say to You (Hong Sang-soo)

In a scene from What Does That Nature Say to You, Ha Dong-hwa (Ha Seong-guk) admits that he often keeps his glasses off because he likes things to look a little blurry. That admission can be seen as the rationale for Hong Sang-soo to shoot the film out of focus to varying degrees, a formal gimmick he employed for the entirety of 2023’s In Water. Throughout, Hong’s technique alternates between inhabiting his protagonist’s perspective and standing outside of it. We are thus allowed to appreciate the sincerity behind Ha’s (Ha Seong-guk) intentions while wincing at his naïveté, the way Jun-hee’s (Kang So-yi) family does both subtly and directly. But though Hong doesn’t spare his protagonist from criticism, nor does he outright condemn him for his faults. If What Does That Nature Say to You’s final scene suggests anything, it’s that growth would appear possible for the seemingly hopeless romantic at the film’s center. Fujishima

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.