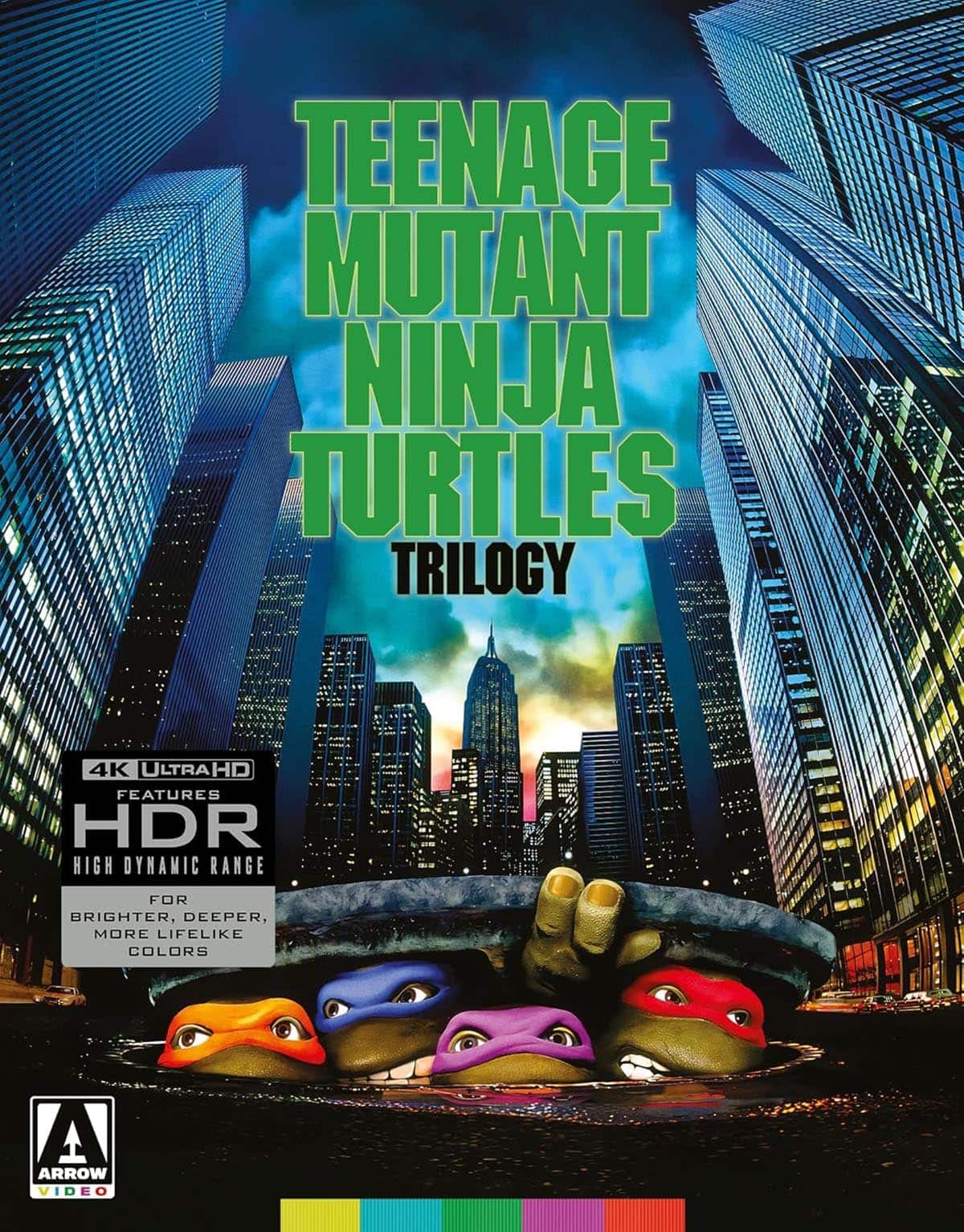

Soon after its debut in 1984, Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles became the biggest breakout success in independent comics history. Conceived as a winking joke on various genre tropes, the series sold so well that it exploded into a multimedia empire, including an animated series, video games, and a toy line. A film adaptation must have felt inevitable, and in appropriate fashion, it was ultimately distributed by the then-independent New Line Cinema after no major studio wanted to take on the project. Fittingly, too, the 1990 Steve Barron-directed feature became the highest-grossing independent feature up to that point.

Soon after its debut in 1984, Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles became the biggest breakout success in independent comics history. Conceived as a winking joke on various genre tropes, the series sold so well that it exploded into a multimedia empire, including an animated series, video games, and a toy line. A film adaptation must have felt inevitable, and in appropriate fashion, it was ultimately distributed by the then-independent New Line Cinema after no major studio wanted to take on the project. Fittingly, too, the 1990 Steve Barron-directed feature became the highest-grossing independent feature up to that point.

Co-financed by Golden Harvest and made with the help of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop, the film ably translates the characters’ unique designs and martial arts moves to live action. Henson’s costumes for the turtles—Leonardo (voiced by Brian Tochi), Donatello (Corey Feldman), Raphael (Josh Pais), and Michelangelo (Robbie Rist)—and their rat mentor, Splinter (Kevin Clash of Elmo fame), are frankly superb, in both their flexible range of motion in the impressive fight choreography and the expressivity of the puppeteer-controlled faces. Yes, the characters’ lips do tend to move the way they do in anime dubs, close enough but not quite in sync with the words being spoken, but there’s a wide range of emotions communicated in some minute shifts in brow and cheek movements.

Still, what’s most remarkable about the film in retrospect, given how the franchise’s tone softened over time to appeal to young children, is just how closely it hews to the comic’s original, slightly more adult tone. The New York City seen here is so derelict that you half-expect Harvey Keitel’s bad lieutenant to come screaming around a corner, and the turtles’ nemesis, Shredder (James Saito), is legitimately unnerving in his cult-like manipulation of the city’s disaffected youth and his willingness to outright torture Splinter to lure out the turtles.

The griminess of the city is still on display throughout Michael Pressman’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze, but the 1991 sequel hews much closer to the lighter, goofier mood that the franchise was known for by that point. The jokes skew far more broad this time around, with a reliance on pop-culture quotes and even the smarter characters behaving inanely. April O’Neil, played in the film with a spunky, dogged attitude by Judith Hoag, is now played by Paige Turco and reimagined as a far bubblier, passive tagalong to our heroes.

So much of the sequel feels like an unsanctioned attempt to make a TMNT film instead of an officially licensed one. Due to Laird’s objections to their use, Shredder’s mutant sidekicks from the cartoon series, Bebop and Rocksteady, don’t make an appearance. In their place are Tokka and Rahzar, whose monosyllabic grunts and one-note comedy make the original henchmen seem Shakespearean by comparison. Jordan Perry (David Warner), the scientist who helped develop the chemical that inadvertently mutated Splinter and the turtles in the first film, is a sympathetic iteration of the mad scientist Baxter Stockman. These changes water down a property that was already parodic and accessible to young audiences into pure juvenilia.

The action choreography is still impressive, and the actors ham it up gamely. (Watch David Warner, relishing the rare chance to play a non-villainous character, taking a bite of pizza and exclaiming with a gourmand’s deep pleasure, “Pepperoni heaven!”) The film’s most enduring scene, of course, comes when a fight sequence breaks through a wall and into a Vanilla Ice concert, whereupon the star launches into an impromptu ninja-themed rap. The scene is so absurd you can’t help but love it, and it’s one of those rare instances of an entire moment in pop-culture history being captured at the one and only time it could have been.

The scattered highs of the second film are nowhere to be found in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles III. The Stuart Gillard-directed 1993 film bypasses the source material altogether to send the turtles back in time to 16th-century Japan, where they find themselves embroiled in a convoluted conflict between a daimyo (Sab Shimono) and oppressed peasants that’s stoked by an English mercenary (Stuart Wilson) in the nobleman’s employ.

In effect, the film is closer in spirit to an adaptation of James Clavell’s Shōgun with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles awkwardly inserted into the drama than an adaptation of the franchise, leading to a jarring collision of childish, reference-heavy humor and the political turmoil of feudal Japan’s pre-Tokugawa period. And whatever merits there are in the production design—including the most expressive puppetry yet and some finely designed villages and filthy castle dungeons—are lost in the flatly lit, perfunctorily composed images and clumsy editing that oscillates back and forth between courtly intrigue and goofball antics.

Image/Sound

Arrow Video’s transfers of the films in the trilogy come from 4K restorations of the original camera negatives, and all three films look as good as they ever have on video. The first and second films in particular boast an exceptional level of detail in the trash-strewn streets of New York and the dank, dripping sewers where the turtles reside. Even the third film’s drab look gets a boost that reveals the rust on iron dungeon gates and the grain of wooden ramparts. Color separation is stable in each transfer, and black levels are deep and crush-free.

Each of the films comes with its original stereo soundtrack and optional DTS-HD MA 5.1 surround audio, and the first movie even includes an Atmos mix. Each of the soundtracks sounds clear and well-balanced, with no instances of overlap between elements or extreme volume discrepancies between dialogue and Foley effects.

Extras

All three films come with commentary tracks by their respective directors, though the most informative commentary may be the one for the first film by comic book expert Dave Baxter, who digs into the multimedia phenomenon that the comic unleashed and how well the first film incorporated elements from the various iterations of the franchise to that point. Across all three films, Arrow has newly commissioned interviews with members of the cast and crew, who discuss everything from the puppetry involved in the creature costumes to the music to the locations and sets. Everyone looks back on the movies with fondness (Sab Shimono, who plays the corrupt daimyo in the third film, even earnestly calls his work on the movie his tribute to Mifune Toshiro) and their enduring enthusiasm is infectious.

There are also trailers, image galleries, and alternate footage from international cuts scattered across the set. A booklet contains essays by filmmaker John Walsh, film producer John Torrani, and film historian Simon Ward that cover everything from the work of the Jim Henson Creature Shop, to the trilogy’s place in the annals of comic-book cinema, to the farcical distribution difficulties in the U.K. due to a ban on nunchaku and even on-screen depictions of them.

Overall

Feel the warm, radioactive glow of early-’90s nostalgia with this trilogy of films, which have received fantastic transfers and a treasure trove of extras courtesy of Arrow Video.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.