Milagros Mumenthaler’s The Currents is a film of layered hints. Basic plot details—what exactly the characters do for a living, the precise nature of their relationships, what really happened between them in the past—are revealed at a trickle, if at all. Others can only be guessed at. This commitment to vagueness can be frustrating, even self-indulgent at times. But considered as a means of getting across the protagonist’s subjectivity, it comes to feel purposeful. For Lina (Isabel Aimé González-Sola), not only are such details in the background of her life, they’re trivial compared to what’s happening inside her mind.

Lina seemingly has everything going for her. Not only is she a successful artist (of some kind), she’s also a wife and mother. The film’s opening finds her in Switzerland receiving a prestigious award. After the ceremony, she wanders to a bridge and jumps off. She saves herself or is rescued, and returns to her life in Buenos Aires, where it doesn’t take long for her wealthy husband, Pedro (Estaban Bigliardi), and her little girl, Sofía (Emma Fayo Duerte), to notice that something in her has slipped askew. For the remainder of The Currents, she struggles against an alienation that neither she nor her family can quite understand.

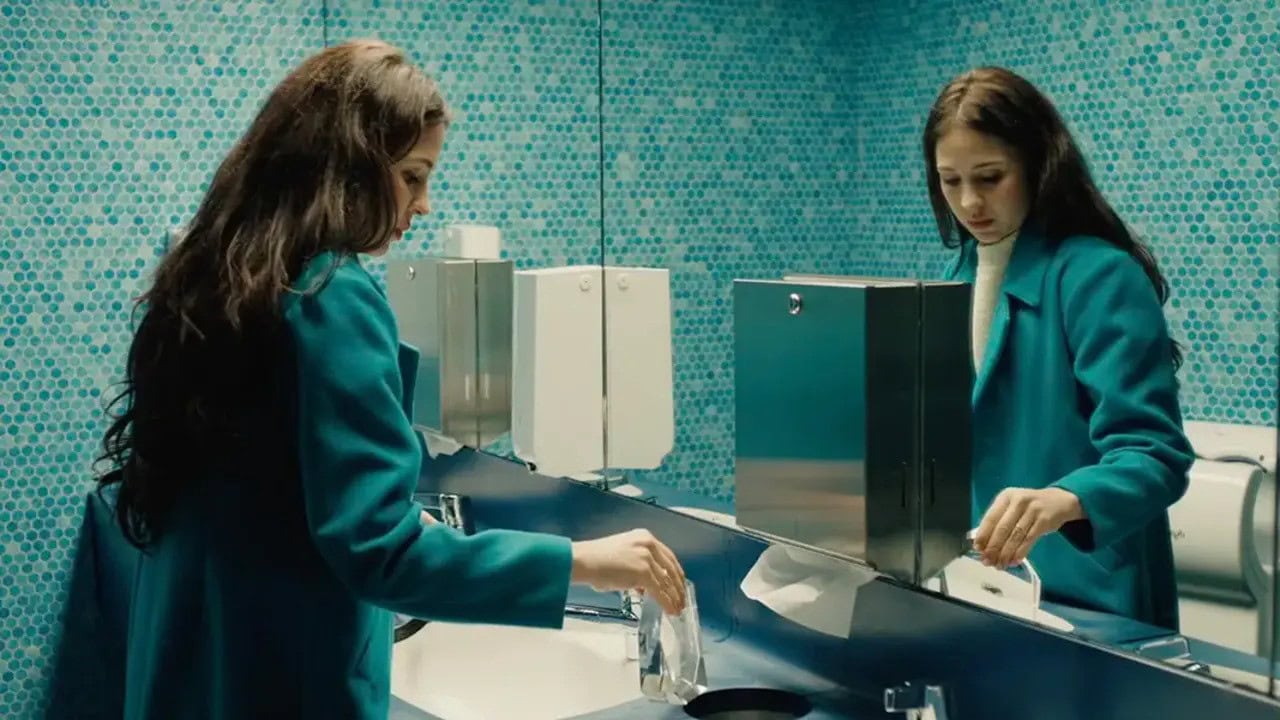

Much is conveyed by Mumenthaler more obliquely than this synopsis suggests. For instance, on Lina’s return to Argentina, her disordered hair outwardly manifests her state of mind. Or the fact that, when she visits her estranged friend Amalia (Jazmín Carballo), she announces herself as Cata as opposed to Lina (both are nicknames derived from Catalina), suggesting an attempt somewhere along the line to distance herself from her past self by changing her name. Such details, in the absence of concrete plot information, take on extra significance.

Through her gaze, Aimé González-Sola intently expresses Lina’s ambivalence toward motherhood, womanhood, even personhood. She always appears to be looking into some underlying emptiness beyond her surroundings. In a few instances, we get glimpses into Lina’s mind, such as the image of swan floating in profound blackness. The Currents recalls Lucrecia Martel’s work, in which effects or symptoms may be visible on screen, but their root causes are kept secret. But Mumenthaler’s attention to metaphor and subjectivity also invites comparison to Virginia Woolf’s formalist yet compassionate illumination of characters’ inner landscapes.

Two scenes in particular are emblematic of this Woolfian quality. The first revisits the film’s opening, which depicted Lina wandering to the river and climbing over a railing in long shot. In contrast, the reiteration is shot much more from Lina’s perspective. As she describes to Amalia what happened, Mumenthaler’s images imbue her (possibly embellished) retelling with a strange nostalgic warmth. This time we see her pause at a shop window to contemplate, as though it were a shrine, an embroidered depiction of women sewing. All that can be heard on the soundtrack are snowfall and Morton Feldman’s “Something Wild in the City: Mary Anne’s Theme”—music that would not be out of place for a fairy tale deemed too dark for children.

In the second, subtly connected scene, Lina faints at the top of the lighthouse above her studio, in the presence of her daughter. For a few minutes, as Holst’s “Venus, the Bringer of Peace” plays on the soundtrack, the camera unhooks from her perspective to try on that of her assistant, Julia (Ernestina Gatti), whom Sofía has just seen entering the Subte station below. Unmarried, working-class, androgynous, youthful, outside the public eye, Julia represents some other version of how to live as a woman and an artist, but also a source of attraction for Lina. Then the camera leaves Julia and goes on to explore the Buenos Aires cityscape at dusk.

This lightly cosmic sequence blurs the line separating what we now call dissociation from a transcendent evacuation of ego. While The Currents can certainly be read as a portrait of a woman coming apart at the seams, it also offers a more expansive view of mental illness as a sensitivity not wholly pathological, but rather capable of reframing and refreshing the world. At a different point in history, Lina might be perceived as a saint.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.