Dating back to more than 2,000 years, a sculpture of Nike, the Greek goddess of conquest, known as the Winged Victory of Samothrace is believed to have been created as part of a larger ancient monument. Since its discovery in the 19th century, it’s come to represent important triumphs, especially in war.

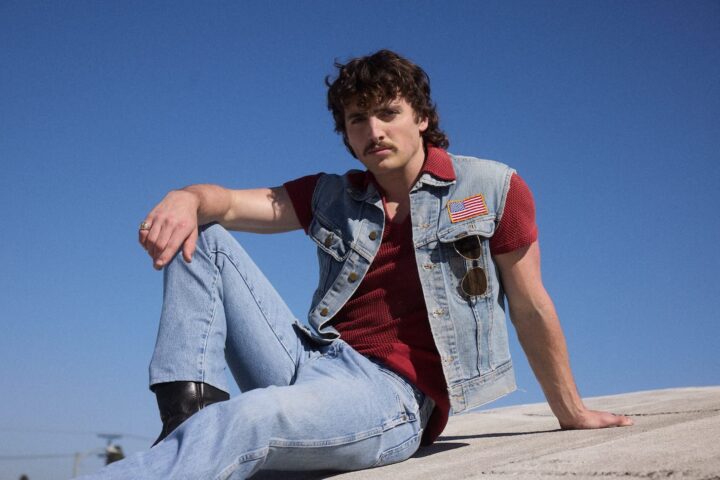

In stark contrast, “Winged Victory,” a track on Willi Carlisle’s album of the same name, is about dead-end jobs, daffodils, and farm animals. In fact, the song’s title refers not to battle, a divine entity, or a work of art, but a donkey. Yet Carlisle sings with such fist-pumping ferocity about America’s unsung workers that he elevates them to the level of myth, and offers an affectingly simple explanation as to why: “I believe in the impossible/That no one is expendable.”

This is the central ethos of Carlisle’s ever-evolving bluegrass oeuvre, including last year’s Critterland: to write with loving specificity about real life in the South, Midwest, and Great Plains for the working class, misfits, marginalized groups, and those making a living outside the law. His eye for detail, which has only grown sharper over four albums, is evidence of a reverent study of folk and Americana, and it allows Carlisle’s original songs to blend with the handful of covers and traditional songs featured throughout Winged Victory.

The album’s opening track, “We Have Fed You All for 1000 Years,” which originated in 1908 in the magazine for the Industrial Workers of the World and was covered decades later by folksinger and labor organizer Utah Phillips, is a paean for workers and an invective against capital. With a voice fuller, grittier, and more impassioned than ever, Carlisle sings, “If blood be the price of all your wealth/Good God, we have paid in full.”

On “Work Is Work,” an original composition in which he looks at economic injustice through a contemporary, intersectional lens, Carlisle sings with deep empathy about sex work, drug use, and financial desperation in a small town flooded by tourists and wrecked by climate catastrophe. That this and “We Have Fed You All for 1000 Years” fit so seamlessly with each other despite having been penned over a century apart speaks not just to the timelessness of both songs, but to the persistence of the social inequities that continue to burden us.

Carlisle is at his best when he juxtaposes musical traditionalism with contemporary sensibilities. On “Big Butt Billy,” he mimics the heteromasculine swagger of country singers like Johnny Cash: “Well, good God almighty, hail Satan/I’ve never seen a finer they/them/Than Big Butt Billy!” The song is a hilarious parade of synonyms for “butt,” morphing from spoken-word cowboy poetry to a fiery sermon about a shining specimen of a rear end. Whether it’s high camp, high art, or both, the song is masterfully penned, completely absurd, and delightfully queer.

Carlisle’s cleverness results in moving observations on politics and mortality just as effectively as it does humor. On the lilting ballad “The Cottonwood Tree,” he takes the phrase “down to earth” literally, finding solace beneath a cemetery as he lovingly describes plants, clouds, and animals interlacing with his decaying body. “If there’s a place up in Heaven/For people like us/I don’t want to go there/There’s no one I’d trust,” he sings, leaving open the meaning of “people like us.” Whatever the sources of his alienation, he resolves to make a heaven of his own in the troubled landscape from which he and his musical inspirations have grown.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.