Last year was one for the books, and 2025 is looking to keep up the pace, with FKA twigs’s sensuous—and, yes, sensual—Eusexua coming on strong just weeks into the new year, followed by a slew of albums that are, at turns, ambitious, introspective, and bold, from Jason Isbell’s deeply personal Foxes in the Snow to Japanese Breakfast’s pointedly titled For Melancholy Brunettes (& Sad Women).

Elsewhere, New York rapper Billy Woods and British noise rockers Benefits have painted grim portraits of the techno nightmare that society seems intent on spiraling further into. But that’s not to say there wasn’t joy or escape to be found in this year’s music landscape so far: TikToker turned pop singer Addison Rae’s self-titled debut has turned out to be an unexpected guiltless pleasure, while Miley Cyrus’s post-apocalyptic visual album Something Beautiful locates light amid the mayhem. Together, the 25 albums below reflect a collective mood that’s far more nuanced than the almighty algorithm would have us believe. Sal Cinquemani

Addison Rae, Addison

Addison Rae’s debut album, Addison, is the hard-won culmination of the TikTok star’s lengthy and public-facing reinvention. It’s a slinky and scintillating album, poised between self-mythology and self-discovery: “Tell me who I am,” she sings in the opening seconds of “Fame Is a Gun”—at once a challenge and a plea. Throughout Addison’s fleet 33 minutes of breathy, sparkling, unapologetic pop, Rae makes roundabout moves to tell us who she is. That the singer never really arrives at an answer is part of what gives the album its conceptual thrust. Addison’s pleasures are right there on the surface, and though it’s compelling as a response to an identity crisis, the music speaks for itself. Like so much good pop music, Addison makes hard work seem like second nature. Alexander Mooney

Aya, Hexed!

Aya’s second studio album, Hexed!, barrels through scenes of drug-induced delirium with unrelenting ferocity, industrial noise colliding at all angles with the U.K. artist’s panicked screams. “Crash! Crash! Crash!” she urges on “Off to the ESSO” amid a maelstrom of metallic clamor, narrating her self-destruction in Manchester clubs. On the equally punishing closer “Time at the Bar,” she cries out as she returns “to a life semi-detached, to things best left unsaid,” both her trans identity and her addiction lingering just out of frame. As much as the album represents a dissociative nightmare, it also distills the cathartic process of self-recognition, every howl, clatter, screech, and fractured lyric an exorcism of suppressed suffering. Eric Mason

Bad Bunny, Debí Tirar Más Fotos

While Bad Bunny’s typical mode is irreverent and hedonistic, the reggaeton star’s seventh studio album, Debí Tirar Más Fotos, is bracing in its wistfulness. On the de facto title track, “DTMF,” the rapper and singer mourns the opportunity to preserve the memory of his native Puerto Rico before it was transformed by tourism and gentrification. The song, which sparked a social media trend of video tributes to loved ones, artfully weaves the musical present and past when its electro-pop production drops out, leaving only the voices of a plena choir. Elsewhere, the enticingly danceable “Nuevayol” gracefully incorporates salsa brass with reggaeton beats as Bad Bunny pays tribute to the legends of Latin music who pioneered the musical styles that he now innovates and showcases worldwide. Mason

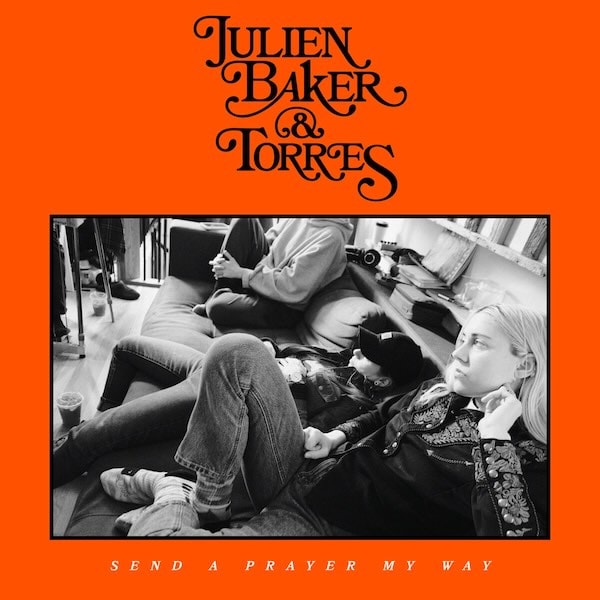

Julien Baker & Torres, Send a Prayer My Way

On Send a Prayer My Way, Julien Baker and Torres reclaim the honky-tonk music they grew up on. With familiar genre hallmarks like pedal steel and banjo, drinking songs, and honey-sweet harmonies, the pair demonstrates a deeper understanding of what makes authentic country music than many of the good ol’ boys in Nashville. The album sounds fresh and contemporary even as it reaches for, and strikingly captures, classic country vibes. Send a Prayer My Way may not reinvent the wheel musically, but by virtue of the fact that Baker and Torres are young, queer women, it does take on a subversive bent that challenges the cultural hegemony that’s all but co-opted the genre in the popular imagination. Jeremy Winograd

Benefits, Constant Noise

While U.K. duo Benefits’s first studio album, 2023’s aptly titled Nails, sounded like an electronic rendition of hardcore, the band’s sophomore effort, Constant Noise, delves into a greater variety of sounds and moods, mixing punk, spoken word, and even a choir. Although tracks like “Divide” and “Lies and Fear” still dip into noise, the group is still as interested in pursuing queasy electronic pop and minimalist arrangements as it is brutal aural assaults. Instead of hectoring the listener, the band inhabits the voices of the subjects the songs are criticizing, like the complacent blowhard who narrates “Missiles.” But whether Benefits is taking on social media toxicity or other digital distractions, the group’s introspective streak is equally as tough. Steve Erickson

Caroline, Caroline 2

Caroline 2 is an album of collisions: between time and space, past and present, precision and spontaneity. The songs never settle, seemingly discovering themselves in real time. The album resists clean structures and resolutions, creating a space where songs feel less like finished products and more like living systems—always in motion and always on the verge of change. Part of what makes Caroline 2 so compelling is how closely its mysteries mirror its methodology. The lore behind the album’s writing and recording—the traveling mic, the cemetery sessions, the collaged demos—feels like an extension of the music itself. The songs build a world you can almost see but never fully grasp. The band understands that not knowing can be its own kind of truth. Nick Seip

Miley Cyrus, Something Beautiful

The songs on Miley Cyrus’s Something Beautiful take their sweet time unfolding, luxuriating in sax solos, spoken interludes, and some loosely defined world-building in service of a post-apocalyptic narrative—something about ego death and the end of the world. The album’s back half, though, is a bona fide barnburner, dropping you into a dystopian discotheque. “Every Girl You’ve Ever Loved” is a feminist anthem that channels ballroom culture, while “Reborn” is dirty, dark, and rapturous. On the album’s final track, “Give Me Love,” Cyrus surveys humanity’s path from paradise to hell, inspired by a copy of Hieronymus Bosch’s painting “Garden of Earthly Delights” that she found at a yard sale in the Valley. In the end, she bids farewell to her “perfect Eden,” perhaps resigned to the realization that love can’t save the world after all. Cinquemani

Deafheaven, Lonely People with Power

On their sixth studio album, Lonely People with Power, Deafheaven steps back from the genre-blurring experiments of their last few efforts to embrace a sound that’s unapologetically heavy. The result is fierce and focused, and it plays like a purposeful throwback. Tracks like “Revelator,” “Doberman,” and “Magnolia” are pure black metal—all relentless blast beats, searing tremolos, and guttural vocal assaults executed with precision and force. The band employs progressive song structures and dynamic contrasts that give even the most feral moments a grand sense of scope, without ever dulling the album’s visceral intensity. Ultimately, the confident, cathartic Lonely People with Power stands as Deafheaven’s most vital release since 2013’s Sunbather. Paul Attard

Erika de Casier, Lifetime

Erika de Casier has been carving out a niche for herself in left-of-center, electronica-leaning R&B for the last few years, and her fourth album, Lifetime, achieves her most successful balance yet between moody beats and featherweight singing. De Casier’s flighty yet unruffled expressions, from the wryness of “You can call me delusional/‘Cuz I’m imagining things as usual” to the overeager offering of “You want a piece of me, baby—you got it,” are all played in the exact same register. Each song is atmospherically fine-tuned with layered details: the horse naying woven throughout “Delusional,” the loping pace and shifty, record-scratch percussion on “The Chase,” and the industrial patter and churn of “Seasons.” Lifetime creates fixed stylistic parameters for itself and operates within them methodically and satisfyingly. Charles Lyons-Burt

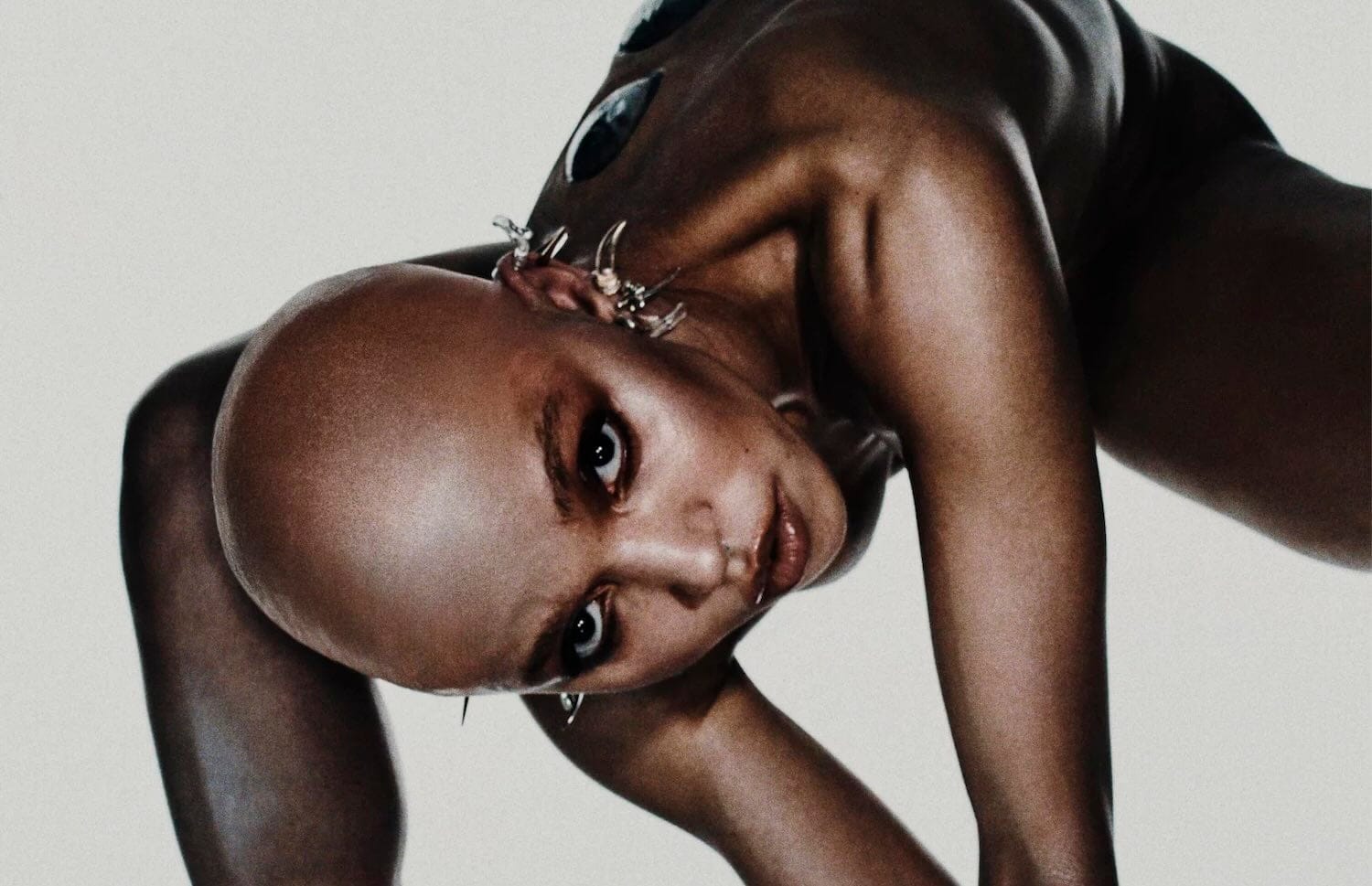

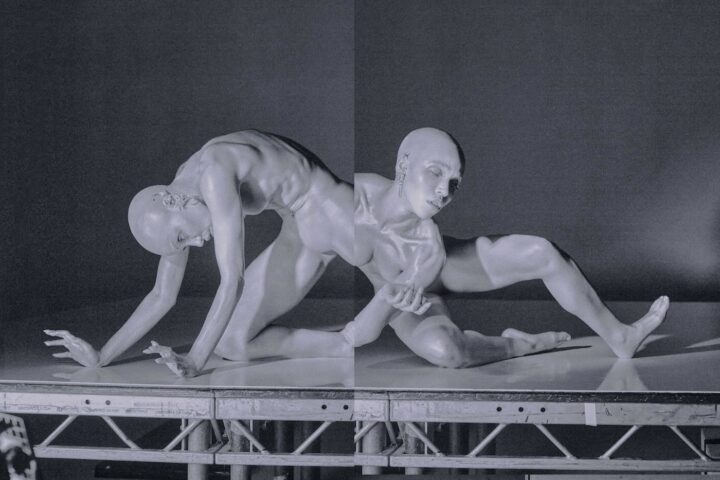

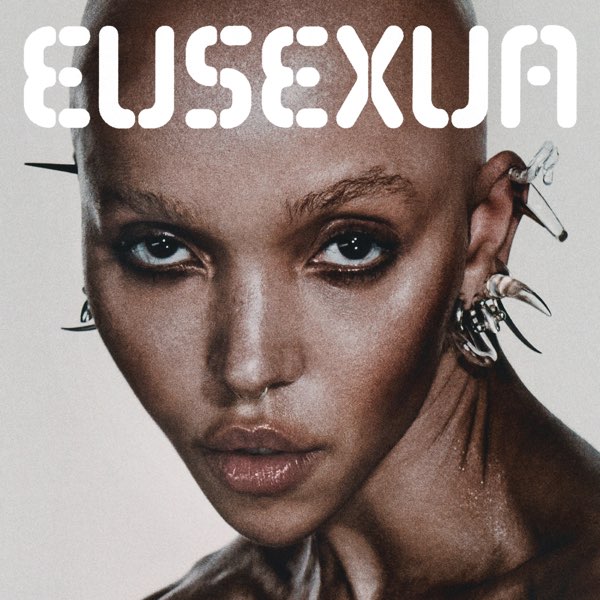

FKA twigs, Eusexua

Where FKA twigs’s debut, LP1, moved like molasses, Eusexua is mostly a briskly paced techno album. It’s propulsive and fun, but, like LP1, it’s wrapped in anguish. On “Sticky,” twigs sings, “I tried to fuck you with the lights on/In the hope you’d think I’m open,” a call-back to “Lights On.” After twigs’s first few projects obsessively catalogued the pains of codependence and stasis, Eusexua presents someone learning to find strength in near-constant movement: “Keep It, Hold It” sees her putting one foot over the other as a means of survival while trying to hold close what’s dear and protect it with all her power. Perhaps this gesture is one of protection against intrusive and abusive men, and this album finds her both focusing on herself and taking refuge in trysts with people she doesn’t—nor cares to—know. Lyons-Burt

Florry, Sounds Like…

In a sea of artists carefully curating their country eras, Philly band Florry stands out as refreshingly carefree. It tracks that they’d cite the Jackass theme song as an inspiration for Sounds Like…. Freewheeling and alive, the album shares a kindred spirit with the lovable chaos of the Jackass crew and the DIY ethos of the Minutemen, who wrote that theme. This is an album that feels like it’s happening right in front of you, right down to the chatter, laughter, and bum notes that the band has left in. Sonically, Florry falls between the alt-country of Jason Molina and the ragged garage rock of Neil Young & Crazy Horse. But while those artists have a tendency for melancholy, Florry’s music feels lighter, scrappier, and sunnier. These are songs for car rides and cookouts, with riffs that hit immediately and melodies that feel lived-in. It’s messy, honest, and joyful. Seip

Fust, Big Ugly

Fust’s Big Ugly is a homespun collection of songs that reflect on love, loss, and the ever-changing relationship we have with the places that made us who we are. The ghosts of old haunt the MJ Lendermann-esque “Spangled” (“I can’t even visit/The last room I may have been”), while the title track is a warts-and-all tribute to one’s hometown (“I love this town, it shows me my lonesome’s written in the stars”). The songs are filled with musings on the human condition, from the grief-stricken “Sister” and its reflections on how life can leave one “wrecked, wounded, wore down,” to the lilting “Mountain Language,” about an intimate relationship giving way to a personal shared language. On the closing track, “Heart Song,” the band speaks to the confusion and listlessness of 21st-century life, giving way to a simple existential question we should all find worth asking: “Have I been okay at living?” Tom Williams

Patterson Hood, Exploding Trees & Airplane Screams

Patterson Hood’s Exploding Trees & Airplane Screams feels like a record the 60-year-old singer-songwriter has been keeping inside him for decades only to finally burst out. The melodic, piano-based songwriting and lush, evocative orchestrations that are abundant throughout represent a level of sonic exploration that Hood has never approached before. It’s some of his most impressive and freshest work in years. On the sweet, sing-songy closer “Pinnochio,” he reflects on lessons gleaned from his favorite childhood film, positioning it not as a symbol of innocence lost but as an instigator for all the life he’s lived since. “It’s a whale of a tale with so many miles to go/But I get a little closer each day to my long term goal,” he muses, making explicit what’s more or less implicit in the new and unexpected sounds of Exploding Trees: that he’s a got a whole lot more life, and music, in him. Winograd

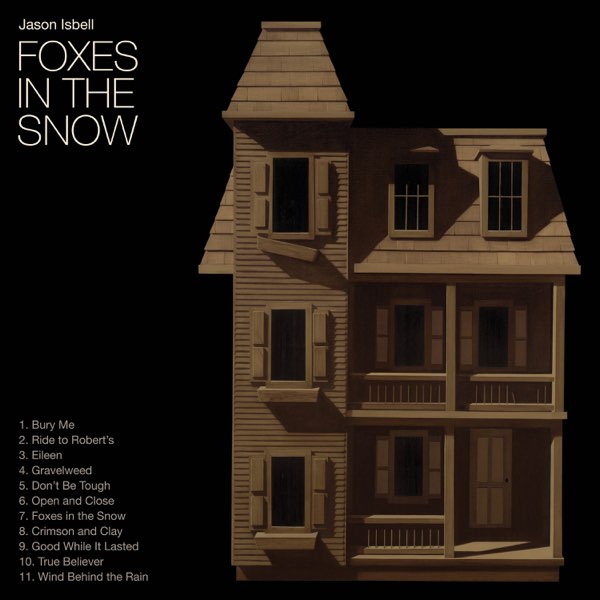

Jason Isbell, Foxes in the Snow

Earnest and quietly distraught, Jason Isbell’s Foxes in the Snow features only Isbell and an 85-year-old acoustic guitar, resulting in his most starkly realized effort to date. Isbell’s disposition is almost uniformly sincere and virtuous throughout. He’s one of the best craftsmen of uncool, old-fashioned, and irony-free country-rock, and the realizations that he’s come to as a sober and more contemplative person are humane in a way that comes close to anti-drama. Despite the chipper bluegrass riff of “Ride to Robert’s,” or the sky-reaching chord changes of songs like “Crimson & Clay,” this is a lonely, tortured album. It begins with an a cappella verse about where Isbell wants to be buried and it ends with a deafeningly minor key note. Like the grand but empty house that adorns the album’s cover art, the comrades who once lit up Isbell’s work, including Shires, aren’t here. It’s incredibly affecting to witness him contend with what that absence means. Lyons-Burt

Japanese Breakfast, For Melancholy Brunettes (& Sad Women)

Japanese Breakfast’s For Melancholy Brunettes (& Sad Women) retreats from the poppy optimism of the group’s 2021 breakthrough, Jubilee, and moves toward a mood similar to the comforting sadness of 2017’s Soft Sounds from Another Planet. The album’s production is imbued with a rich sense of depth and warmth, anchored by intricate interlocking guitars, long-tailed reverbs, and ambient orchestral arrangements. It represents a significant sonic step forward for Japanese Breakfast—it’s the first of the band’s albums to be recorded in a proper studio—while preserving a familiar moody tone. The kind of melancholy that singer-songwriter Michelle Zauner explores here isn’t simply sadness itself, but the possibility of sadness as fertile ground for transformation. Seip

Little Simz, Lotus

After her 2022 album No Thank You, which came in the wake of getting ripped off by her former manager, Little Simz scrapped four albums following alleged financial exploitation by Inflo, her ex-producer. “Thief,” a track from the English rapper’s sixth studio album, Lotus, takes direct aim at Inflo. Born out of feelings of deep-seated betrayal, the album aims toward something more optimistic, as Little Simz’s sound remains grounded in cinematic ’70s soul, while adding a touch of Afrobeat and spiritual jazz. But while the music is often soothing, you don’t have to dig hard to hear the rapper’s disgust with the music industry and her circle of friends. Her rage, when she chooses to show it, rattles furiously. Erickson

Oklou, Choke Enough

Oklou’s Choke Enough exists in a strange, beautiful in-between space—between the ambient and clubby, the hazy and crystalline, and the medieval and modern. The artist herself has described the album as a quest for meaning, and the music reflects that. Upon first listen, Choke Enough can feel distant, even coded. But give it time and it begins to unfurl. There’s a kind of quiet magic at work here: The vocals are lush but never indulgent, and the production is sleek and textural, detailed but never showy. You get the sense that many of these songs could explode into full-on club tracks, maybe even into pop ballads—but they don’t. That restraint gives them their power. This is an album that rewards curiosity. It doesn’t explain itself, but rather draws you in to explore. Seip

Perfume Genius, Glory

On Glory, his seventh studio album as Perfume Genius, Mike Hadreas dials back the climactic pop of his recent work in favor of subtler compositions that lurch and wobble over layers of alt-rock and orchestral instrumentation. From this ornate environment, Hadreas delivers tactile poetry and pained self-examinations, extracting catharsis from isolation and anxiety. Even with Blake Mills’s painterly production, Glory feels compact and introspective, with a current of uneasiness that harks back to 2010’s mournful Learning. In the spirit of finding beauty in confinement, the album’s final tracks make lethargy and uncertainty sound blissful, and Hadreas and Mills imbue even moments of reflective quiet with simmering intensity. Mason

Pink Pantheress, Fancy That

PinkPantheress’s latest mixtape, Fancy That, marks a decided shift from the primarily U.K. garage of her debut studio album, Heaven Knows, toward more overt four-on-the-floor club music. The two-and-a-half-minute opening track, “Illegal,” serves as a primer for what follows, kicking off with a familiar 2-step rhythm and a sample of the sleek synth pads from Underworld’s iconic “Dark & Long (Dark Train)” before building to a 4/4 beat for a succinct but sublime 30 seconds. The longest track on Fancy That barely scrapes the three-minute mark, though that seems epic compared to the tracks on the English singer’s 2021 mixtape To Hell with It. And yet, in just over 20 minutes, it still manages to leave a distinct impression. Cinquemani

Jane Remover, Revengeseekerz

In a remarkably compressed run of three albums made from ages 17 through 21, Jane Remover has signaled their agitation and stylistic restlessness, but none of their work so far has brought that to bear as forcefully as Revengeseekerz. The album pummels you from the start with everything from clattering percussion to crushing bass. And songs are unstable, reformulating or recalibrating midway through, marked by explosions and beat switches. “Dancing with Your Eyes Closed,” for one, has a fittingly unstable gait, and sound seems to come from every direction, like a roof caving in on itself, on “Psychoboost.” Chaos calcifies into rhythmic bliss on “Experimental Skin,” and the hooks waft out of “Star People” despite the whole thing sounding like a blaring alarm system. Revengeseekerz is aurally assaultive, but beneath all the sonic detritus you’ll find surprisingly thoughtful and well-considered lyrics about self-destruction and a young person’s expanding, pained relationship to the world. Lyons-Burt

Swans, Birthing

Since reforming in 2010, Swans have made a habit of testing the patience of their audience in pursuit of transcendence, often rewarding that perseverance with profound and overpowering listening experiences. Birthing, a two-hour album with an average track length of about 16-and-a-half minutes, continues that tradition but is even slower, heavier, and more ominous. Throughout, Swans approaches something closer in spirit to free jazz than rock music, shifting fluidly through a wide variety of tempos, tones, and harmonic movements, all while maintaining a methodical, machine-like precision. This band has always asked a lot of its fans, and with Birthing, it flat-out demands your complete willingness to enter the void. And yet, rather than sounding drained or diminished by that darkness, Swans remain astonishingly vital 17 albums into their career. Attard

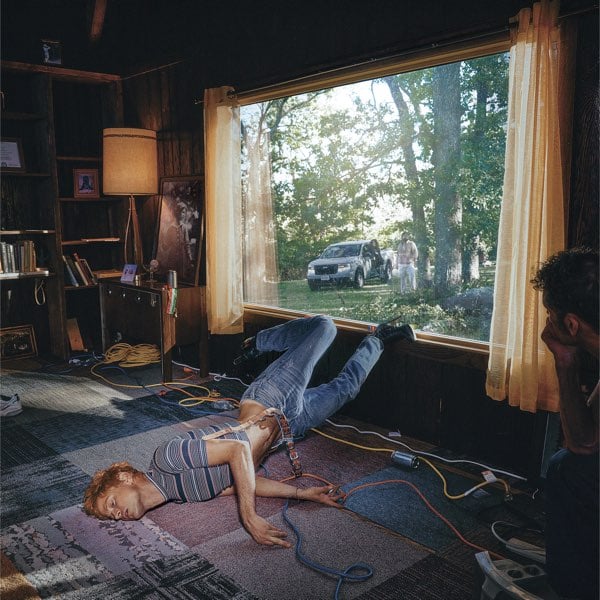

William Tyler, Time Indefinite

After approaching jam-band nirvana on 2023’s Secret Stratosphere, a live album with the Impossible Truth, Nashville guitarist William Tyler retreats far from the wide-open desert-rock soundscapes he’s familiar with and ventures into the dark corners of his mind on Time Indefinite. Several tracks feature no guitar at all, with Tyler favoring decaying tape loops and unsettling dissonance that veer into horror-soundtrack territory, such as “Star of Hope” and “A Dream, A Flood,” which evoke a haunted carnival ride. The enveloping sense of doom that courses through Secret Stratosphere makes Tyler’s tender acoustic picking on “Anima Motel” and “Held” sound that much sweeter. Winograd

Cameron Winter, Heavy Metal

Stripped-back, strange, and deeply intimate, Geese frontman Cameron Winter’s Heavy Metal trades the band’s typical bombast for lyrical surrealism and raw, theatrical vulnerability. From the off-kilter poetry of opener “The Rolling Stones” to the slow-burning gospel climax of “$0”—where Winter wolfishly babbles, “God is real/God is real/I’m not kidding/God is actually real”—his croaking, Jim Morrison-esque drawl remains the magnetic, if polarizing, center. Musically, the album drifts through skeletal piano ballads, freaky lounge jazz, and weirdo pop, sometimes minimalist, other times lush, and always unquantifiable. It’s a confessional and chaotic album, one that toys with sincerity and absurdity in equal measure, but always in refreshingly fearless ways. It’s a bluesy lo-fi odyssey of unruly emotion, oddball wit, and, at times, overwhelming beauty. Attard

Billy Woods, Golliwog

With Golliwog, Billy Woods has crafted a body of work that’s both sonically immense—thanks to a production team of underground heavy-hitters, from the Alchemist to Atmosphere’s Ant—and lyrically precise and unsparing. His observations and insights span the overwhelming bigotry of the internet (“Leave the comments on, the racism pouring in”), the lingering societal and economic legacies of colonialism (explored on the hypnotic “BLK ZMBY”), and the ghosts from the past that never seem to escape us (as captured in the desolate “Golgotha”). Golliwog is intensely confrontational and makes no effort to hold your hand. But challenging times demand unapologetic art to reflect them and offer no easy answers or catharsis. In a landscape where much of modern art and music seeks to soothe or entertain, Golliwog stands as a brutally beautiful reminder that sometimes the only way out is through. Attard

YHWH Nailgun, 45 Pounds

YHWH Nailgun’s 45 Pounds is one of the most adventurous rock albums in recent memory—if you can even call it rock. It’s twitchy, volatile, and hard to pin down. “Blackout” lands closer to Death Grips than anything in the current rock landscape. Everything about the NYC band’s approach feels off-kilter in the best way. The songs are built around the drums—rototom-heavy, technical, almost melodic. The guitars barely sound like guitars, and the synths are huge and bright. Poetic vocals come in like whispered screams from the back of the mix, gasping for air beneath the noise. And yet, there’s a poptimist strain lurking beneath the album’s punishing intensity. Spelling out “tear pusher” on the song of the same name feels more Village People or Chappell Roan than noise rock. On closer “Changer,” a floating, ghostly “Oooo” hints at something gorgeous, and suggests that YHWH Nailgun could go absolutely anywhere. Seip

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.