As A.I. has become ubiquitous and its creators’ contempt for human-made art has grown louder, questions around what it means to be human in a tech-dominated world have taken on more existentially weighty dimensions. Certainly films have plumbed these questions for decades, but exploring them in new, adventurous ways feels essential in the face of technological forces seeking to stifle, and eventually, eradicate the art form.

Fortunately, filmmakers from around the world have met this challenge with resounding ambition and ingenuity. Two very different films, Carson Lund’s Eephus and Sam Crane and Pinny Grylls’s Grand Theft Hamlet, focus on the need for and power of community in disappearing and unconventional spaces, respectively. Meanwhile, Sarah Friedland’s Familiar Touch grapples with the inevitable decline of the body and mind in old age, while David Cronenberg’s The Shrouds goes one step further, contemplating how grief and technology can perversely shift our relationship to the human body of a loved one after they’re gone.

Of course, part of being human is also ruminating how we’ve gotten ourselves into the geopolitical messes we constantly find ourselves in. And no less than two of our favorite films of the year so far examine the lingering repercussions of colonialism on 21st-century life, while an essay film by a German filmmaker holds up a mirror to America, pointedly chronicling the perpetual gulf between how a nation sees itself on the silver screen and how it really is.

Elsewhere on our list you’ll fine magnificently tender, intimate, and funny films about humanity on a more micro scale. Eva Victor’s Sorry, Baby and Rungano Nyoni’s On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, in particular, fearlessly confront the ongoing struggle of women to maintain bodily autonomy in surprising and illuminating ways.

Collectively, these 20 films are a rebuke to the autocratic tech bros who reduce humanity to dollar signs, displaying not only the unquantifiable value of human expression, but its vitalness in keeping us in touch with both who we are and who we want to become.

Editor’s Note: Films that had a one-week awards-qualifying run in 2024 that we were able to screen ahead of publishing our 25 Best Films of 2024 feature weren’t eligible for this list.

Afternoons of Solitude (Albert Serra)

The tantalizing difficulty of pinning down Peruvian matador Andrés Roca Rey’s motivations, let alone director Albert Serra’s stance toward bullfighting, can make Afternoons of Solitude an uneasy viewing experience, at once immersive and distancing. Whatever feelings you may have with this mixture of pageantry, masculinity, barely sublimated ritual sacrifice, nationalism, and sensuality, Serra’s first documentary affords ample opportunity to explore them. It’s hard to shake the suspicion, though, that Afternoons of Solitude is only incidentally about bullfighting. Considered in the context of his other work, it may be that Serra’s real, secret subject here is a protean need to brush up against death, to taunt it, even inflict it, in an irrational, futile, at times beautiful effort to shrug off its inevitability. William Repass

April (Dea Kulumbegashvili)

April’s point of view mirrors that of Ia Sukhitashvili’s Nina. Her primary line of work involves operating out of a hospital maternity ward in the rural eastern reaches of Georgia, but she also takes care of pregnancies in a different way by performing illicit abortions in homes. Nina senses no cognitive dissonance in her dual functions, nor does she feel a need to compartmentalize the two roles. A steely but soulful Sukhitashvili keeps Nina’s motives aptly inscrutable as the woman is torn between her professional duties and her personal feelings. But like the ever-present breathing noises that permeate the soundscape of April, so, too, do the traces of her hardscrabble humanity peek through the film’s austere images. April is always at its most compelling when Dea Kulumbegashvili grounds a scene in the immediacy of Nina’s presence, even if she’s only peeking into a shot from the edge of the frame. Marshall Shaffer

Bring Her Back (Danny and Michael Philippou)

Danny and Michael Philippou brought filmmaking swagger to Talk to Me that made it feel fresh despite its familiar elements. And while they delight in serving up needle drops and applying a freely tilting camera to precise and intense effect, Bring Her Back is ultimately less ostentatious in style than its predecessor, with more attention paid toward smart passages of shallow-focus photography and the liquid textures of blood, drool, piss, and especially rainwater, giving the impression that the film is itself bleeding out, bleary-eyed, and weeping Bring Her Back was written in tandem with Talk to Me, so it’s no surprise that both center adolescent abuse, neglect, and the loss of parents and children, but Bring Her Back has a white-hot nerve of pain running inside it that burns right through the screen. Rocco T. Thompson

Caught by the Tides (Jia Zhang-ke)

Jia Zhang-ke’s Caught by the Tides attests to the fact that making art under the most adverse conditions can prove to be serendipitous. If shooting a film from scratch wasn’t feasible under China’s restrictive Covid lockdowns, Jia viewed the situation as a formal constraint, in the same way a poet might approach the rules of a sestina. Turning to his existing body of work, he recycled earlier material, editing together unused footage with what could be shot under the circumstances. The result is a bricolage of documentary, minimalist drama, and experimental remake. As Jia’s filmography is inseparable from the career of his spouse and longtime collaborator, actress Zhao Tao, the film also operates as a dual retrospective. Repass

Eephus (Carson Lund)

Carson Lund’s Eephus subtly tasks us with thinking of its characters as extensions of the titular pitch: weapons of deception and surprise, not least of which for how they increasingly reveal their passion for the sport and each other as the final game between their teams at an intramural field due to be paved over unfurls. Though set in the 1990s, Eephus feels keyed to the current anxiety over the erosion of public gathering spaces and America’s so-called loneliness epidemic. While the characters care deeply for baseball, their desperate efforts to prolong the game, in lieu of making far simpler plans for future meet-ups, make it obvious that their reasons for doing so go well beyond sport. It’s an irony that hangs over the final stretch of the film, and it’s one that Lund treats with elegiac empathy for the power of a shared interest. Jake Cole

Familiar Touch (Sarah Friedland)

In Familiar Touch, the effects of dementia on octogenarian Ruth Goldman (Kathleen Chalfant) grow gradually more pronounced as her stay in assisted living stretches on. Director Sarah Friedland seeks to foster a kind of physical connection between the viewer and her subject that isn’t rooted in pity, and eventually Ruth’s comprehension of time’s passage comes to subsume Familiar Touch’s perspective. The film feels as comfortable resting on a close-up of Chalfant’s face to demonstrate the quiet tragedy of a moment as it does observing a scene play out from a sterile distance. Yet Friedland resists reducing Ruth’s ailment to simply an aesthetic experience. At the heart of Familiar Touch is the character’s hard-earned humanity, and Chalfant’s performance soulfully plays the immediacy and intimacy of each moment on screen, and not only because it will soon become all that Ruth has to hold onto. Shaffer

Grand Theft Hamlet (Sam Crane and Pinny Grylls)

Shakespeare knew that he was writing for those in the cheap seats just as much as he was for the wealthy patrons of the Globe Theatre, and there’s something perfect about hearing the Bard’s dialogue recited without irony using a video game’s assets in a virtual analog for Los Angeles. After a while, even with all the violence and unfocused hate and logistical nightmares of the world against the cast and crew, the whole endeavor becomes just another theater production with all of its highs and lows. Grand Theft Hamlet’s biggest flaw is that we only see a small piece of the final product. But we see enough of it for the film to magnificently make its ultimate point. In the words of its lead actor, and his shirtless, goateed, princely avatar, as he catches a hail of bullets yet again: “You can’t stop art, motherfuckers.” Justin Clark

Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes)

Miguel Gomes’s Grand Tour takes its title from an established travel itinerary known as the Asian Grand Tour, a popular option with Westerners seeking a broad but surface-level introduction to the continent in the early 20th century. Proceeding from Mandalay to Rangoon (present-day Yangon) to Singapore, and then on through Bangkok, Saigon, Manila, and Osaka, before ending in Shanghai, the tour was ideally designed to satisfy the era’s popular taste for Eastern exoticism in an efficient, tourist-friendly package. It’s easy to see the appeal for Gomes, a director for whom boundaries of space and time have always been ripe for cinematic manipulation. Grand Tour retraces the steps of the journey with the imagination and playfulness of his best work, indulging its globetrotting impulses while casting a satirical eye on its uncomfortable basis in colonial conquest. Brad Hanford

The Gullspång Miracle (Maria Fredriksson)

The Gullspång Miracle, the chronicle of a family reunited, skillfully unfolds what initially seems like an ordinary tale of lives being lived by the most ordinary of people into a dramatic tale of mythological proportions. It steers clear of the feel-good vibes pedalled by the genealogy series Who Do You Think You Are?, suggesting that the telling of any family history is more fantasy than facticity. The various twists here place the documentary in kinship with Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell, for the way it teaches us that identity writ large relies on a series of fragile misrecognitions that cinema can only hope to expose and complicate, not resolve. Supported by the strategic aesthetics of a murder mystery, Maria Fredriksson’s film is actually a philosophical account, and a delightfully immersive one at that, of the shaky ground—a mixture of lies we’ve been told and lies we’ve told ourselves—that human existence stands on. Diego Semerene

Henry Fonda for President (Alexander Horwath)

Alexander Horwath’s Henry Fonda for President rigorously unpacks the implications of Henry Fonda’s screen image. The film charts a more-or-less chronological course through American history and Fonda’s own life through the prism of his screen roles. Despite the mournful anti-war tone of Drums Along the Mohawk, its depiction of a Dutch settler community could still work as a “manual to genocide”; the Tombstone that Wyatt Earp cleaned up now exists as a tourist trap squeezing the last few dollars to be made out of the myths of the West; the exploitation that Tom Joad fought against in the migrant camps of the Salinas Valley is now more brutally visited upon Mexican workers. If Fonda was an avatar of American liberalism’s tolerance and self-scrutiny, the film suggests, so, too, does he represent its complicity in the nation’s sins and its failure to change its course in the direction of justice. Hanford

Misericordia (Alain Guiraudie)

Fans of Alain Guiraudie’s work may take the opening sequence of Misericordia as a sign that they’re in familiar terrain. A view from behind the windshield of a car winding its way through back roads to a small hillside village, it announces the premiere chronicler of lust and violence in the French countryside’s return to the milieu in which he made his name. Indeed, Misericordia finds Guiraudie revisiting old standbys—a linking of queer desire and mortality, a distanced but lighthearted absurdism, and a refusal to get moralistic about transgressive behavior—under a relatively conventional set of aesthetic strategies. Fortunately, the ideas roiling under the former wildman’s newly placid surfaces are as potent as ever. Hanford

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl (Rungano Nyoni)

Like Rungano Nyoni’s feature debut, 2017’s I Am Not a Witch, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is interested in the defiance of entrenched patriarchal custom and the ways in which her native Zambia’s more traditional values clash with modern secular and commercial ones. Here, a prodigal daughter’s return home is immediately disrupted by a tight-knit community desperate to bury anything that might upset the apple cart. A small bird that asserts itself through a high pitch that’s meant to warn others when a predator is nearby, the guinea fowl is something of an obvious allegory, but On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is, more deeply, about the process in which people are often thrust into roles of reluctant heroism and solidarity. Greg Nussen

One of Them Days (Lawrence Lamont)

Lawrence Lamont’s One of Them Days is very much the heir apparent to a class of Black comedy that had started to fade away long before the rest of the theatrical comedy landscape followed suit. That is, a sort of slice-of-life, single-day-in-the-city movie without a high concept in sight. It’s a throwback hangout flick above all, and like the best of them, it plays out just absurd enough to support jokes but honest enough in that there’s plenty of time given over to capturing warm little moments of friendship between the characters. There’s nothing particularly new or unique about the journey that Dreaux and Alyssa go on, but it’s still a joy to experience simply because we’re in the company of Keke Palmer and SZA, leads with such an easy, effortless chemistry and unique comic timing, with Palmer as the slick, quick-thinking, fast-talking straightwoman to SZA’s pseudo-spiritual agent of passive chaos. Clark

The Phoenician Scheme (Wes Anderson)

Throughout The Phoenician Scheme, it’s easy to draw a line between Zsa-zsa Korda’s (Benicio del Toro) revelation that his greatest accomplishment is something he’s meant to give away and Wes Anderson’s stylistic maturation. There’s always been authenticity lurking under the filmmaker’s artifice, but the raw emotion underlying this film peeks out at unexpected times. For a work that’s never short on pithy verbal irony, The Phoenician Scheme’s most profound irony is embedded in its structure. A life and its work cannot be compressed and compartmentalized neatly into boxes, no matter how hard the protagonist or his creator might try. No dam that Korda funds or diorama that Anderson creates can withstand death. Building up a legacy is what ultimately matters for both men. Anderson may not preach this message as gospel, but the way he communicates it is indelibly graceful. Shaffer

The Shrouds (David Cronenberg)

One could see in The Shrouds a cautionary tale of the limits of technology in dealing with complex human emotions, especially when such technology can be so easily manipulated by outside forces. Even more disquieting is David Cronenberg’s refusal to pass easy judgment on Karsh Relikh (Vincent Cassel), who, in response to the death of his wife, Becca (Diane Kruger), creates a technology that allows people to monitor their loved ones’ corpses with the help of special shrouds—outfits with many tiny X-ray cameras embedded inside—that they don when they’re underground. The Shrouds may see a great filmmaker in a more settled frame of mind, but that doesn’t mean that his inner provocateur is dormant, as he’s still clearly willing to dive headfirst into the depths of twisted human desire. Kenji Fujishima

Sinners (Ryan Coogler)

Remarkably, Sinners delays the reveal of its genre bona fides for nearly its entire first half, devoting time to establishing the quotidian horrors of Jim Crow Mississippi. The film’s most bravura moment doesn’t even hinge on vampire carnage. Instead, it’s a spotlight on music, which Sammie (Miles Caton) plays with such heart that he begins to commune with the history of Black music, past, present, and future. This transcendent show of solidarity ultimately becomes the subject of a fascinating contrast with the vampires who descend upon the juke joint. The images of voracious white predation are potent, but Coogler pushes past this obvious metaphor for something more provocative as Remmick (Jack O’Connell) slowly turns his growing mass of thralls into a musical troupe of his own. Not unlike the Hands Across America parody of Jordan Peele’s Us, an image of harmony becomes a sick reminder of the illusion of “post-racial” life in a nation founded on ethnic hierarchy. Cole

Sorry, Baby (Eva Victor)

Eva Victor’s feature-length directorial debut, Sorry, Baby, lives intently with this sense of dissociation that Anges (Victor) feels in the wake of a sexual assault as she struggles to reconcile what’s happened to her with what the rest of her life will be. And it rather brilliantly keys us to the unsettling paradox in her ordeal. Agnes will be fine, and her life will go on exactly as it did before. Agnes is a complete wreck, and nothing will ever be the same again. It feels like, after we’ve reached this point in Agnes’s story, nothing could ever be funny again either. No doubt that’s how life feels for the character too. And yet, Sorry, Baby somehow manages to mine so much humor from the absurdities that Agnes faces from there on out, and without ever downplaying the severity of what happened to her. Ross McIndoe

Who by Fire (Philippe Lesage)

More than anything, Philippe Lesage’s Who by Fire is a film of great freedom, using its 161-minute runtime to act as a container for a profusion of scenarios, continually deepening the tensions between characters that slowly develop while maintaining an outwardly convivial, even exuberant atmosphere. The sense of play extends to characters literally bursting into song, including a rollicking (and hilariously plot-relevant) group dance to the B-52s’s “Rock Lobster,” but is typically expressed by Lesage’s facility with camera movement. A few scenes set around the central dining table are incredibly expressive, as in one long take where the camera drifts over the table into seemingly impossible positions. The effect of this and many other sequences is the suggestion that anything can happen at any given moment, even violence. Ryan Swen

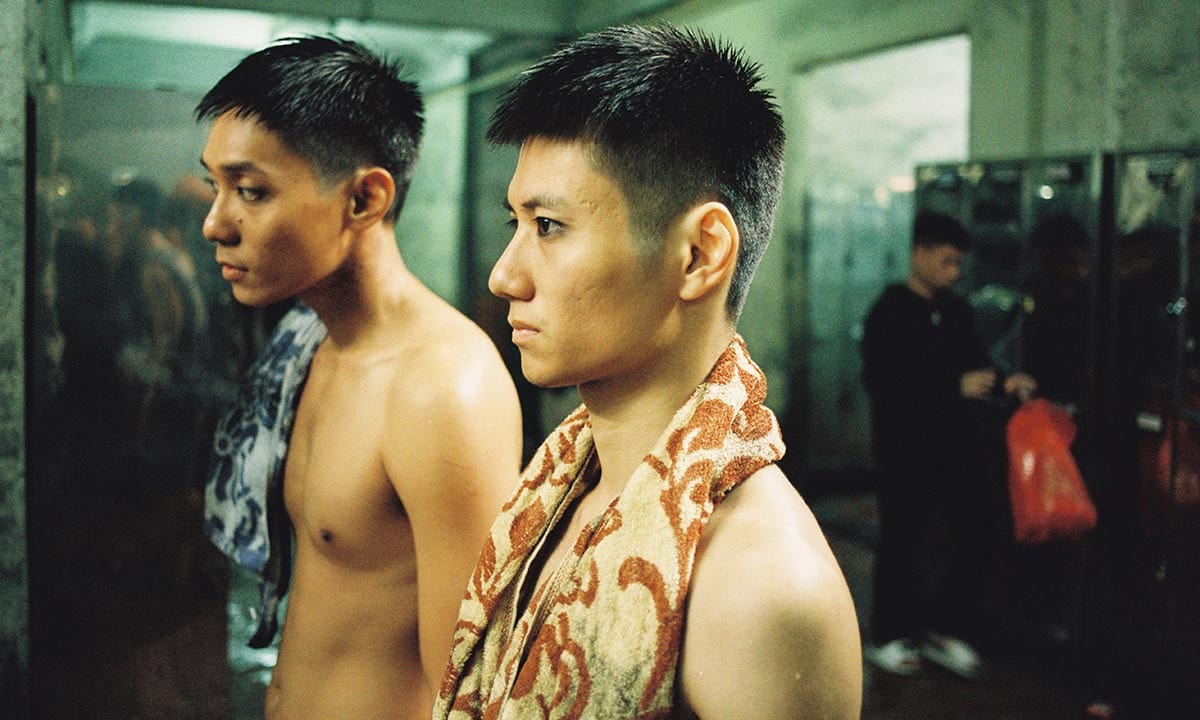

Viet and Nam (Truong Minh Quy)

Deliberately paced and prone to indulge in poetic intermezzos, at once earthy and otherworldly, Truong Minh Quy’s Viet and Nam has earned comparisons to the work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, among others. But if the film is conversant with many of the prevailing trends in international art cinema, Quy doesn’t shy away from staring down the incensing specificities of current events. Quy has said in interviews that his film was at least partially a response to the deaths of 39 Vietnamese refugees, discovered in a refrigerated trailer outside of London in 2019. And interestingly enough, the further Viet and Nam progresses into its increasingly symbolic and fragmented second half—forget Weerasethakul, Quy at times seems to be channeling Muriel-era Alain Resnais—the more direct and polemical it also becomes. Eric Henderson

Vulcanizadora (Joel Potrykus)

What most stands out about Joel Potrykus’s work is its relationship to time. Channeling the cynical, anti-conformist ethos of ’90s pop culture, Potrykus evokes the era of his teenage years with a light touch, to the point that we may wonder whether his characters are devoted nostalgists or actually living through the end of the 20th century. Vulcanizadora revisits two characters—Marty (Joshua Burge) and Derek (Potrykus)—introduced a decade ago in Buzzard. In projecting forward into the later lives of his amusing, troubling creations, Potrykus looks without flinching at the consequences of permanent adolescence, a frequent subject of light comedy but one rarely treated with any real weight. The film stands as a model of serious, engaged filmmaking that grows richer and more poignant as time goes by. Seth Katz

Honorable Mention: 28 Years Later, Blue Sun Palace, Direct Action, The Fishing Place, Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, Predator: Killer of Killers, Sly Lives! (aka the Burden of Black Genius), The Ugly Stepsister, Young Hearts, The Visitor

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.