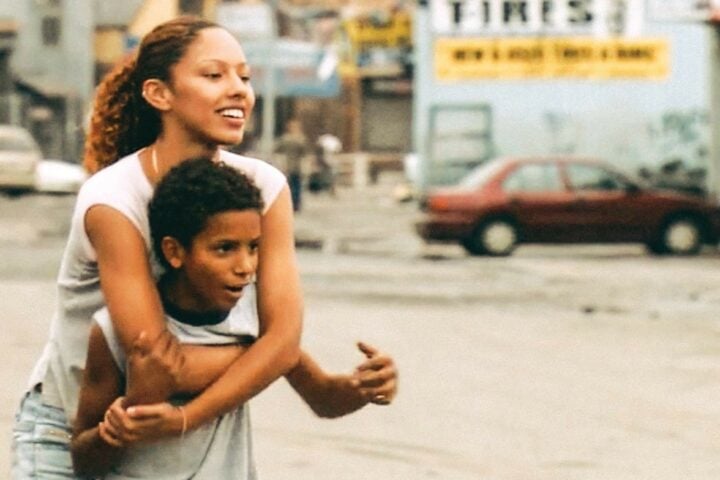

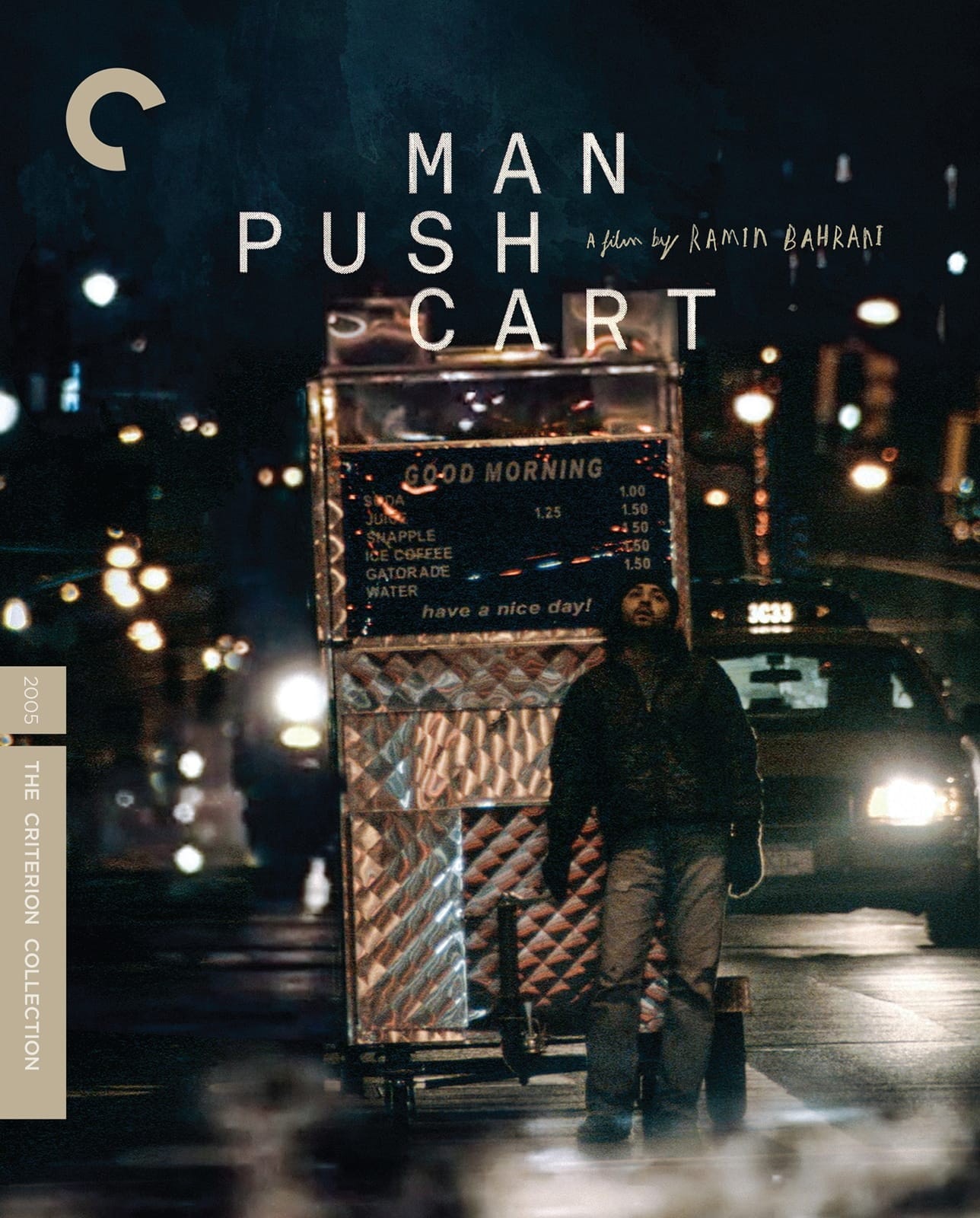

Ahmad (Ahmad Razvi) suggests a modern-day Sisyphus, finding himself condemned by tragedy to spend his days and nights pulling his coffee and donut cart through New York City’s bustling streets, his load a symbol of his inescapable sorrow. Writer-director Ramin Bahrani’s Man Push Cart follows its forlorn protagonist—a former pop singer known in his native Pakistan as “the Bono of Lahore”—through his grueling dawn-to-dusk routine of lugging his stand and propane tank to and from his proscribed city corner, stacking muffins and prepping paper cups with teabags, trying to sell bootleg porn DVDs in his free time, and occasionally venturing out to nightclubs with his Westernized Pakistani friends.

Ahmad (Ahmad Razvi) suggests a modern-day Sisyphus, finding himself condemned by tragedy to spend his days and nights pulling his coffee and donut cart through New York City’s bustling streets, his load a symbol of his inescapable sorrow. Writer-director Ramin Bahrani’s Man Push Cart follows its forlorn protagonist—a former pop singer known in his native Pakistan as “the Bono of Lahore”—through his grueling dawn-to-dusk routine of lugging his stand and propane tank to and from his proscribed city corner, stacking muffins and prepping paper cups with teabags, trying to sell bootleg porn DVDs in his free time, and occasionally venturing out to nightclubs with his Westernized Pakistani friends.

Bahrani’s portrait of existential urban malaise posits a world in which Ahmad’s interpersonal interactions lead merely to further humiliation and misery, from his tense dealings with a Pakistani businessman (Charles Daniel Sandoval) and the accusatory mother-in-law (Razia Mujahid) who won’t let him see his son (Hassan Razvi), to his awkward relationship with Spanish newsstand vendor Noemi (Leticia Dolera) to whom he’s incapable of expressing his tentative romantic feelings. The film heightens its overall sense of fatalism through a moody depiction of midtown Manhattan as a place of cheerless nocturnal shadows and faces, a pessimism that it occasionally alleviates with brief moments of tenderness, such as Ahmad’s care for the tiny kitten that serves as a surrogate for his real offspring.

The film’s tight compositions effectively mirror the oppressive constrictiveness of both Ahmad’s cart and the weight of his grief. But Man Push Cart is ultimately one-note, exuding a cold, omniscient perspective that increasingly becomes akin to that of a scientist clinically watching a rat futilely search for a bite of cheese at the end of a maze. And finally, the filmmaker’s labored attempts to avoid trafficking in hope have the deleterious effect of casting nearly every scene as a disingenuous, pedantic example of the cosmos’s callous cruelty.

Image/Sound

Criterion’s high-definition digital transfer of Man Push Cart, supervised and approved by Ramin Bahrani, beautifully enhances the gritty urban textures of the filmmaker’s raw portrait of immigrant life in post-9/11 New York City. The image is consistently sharp, and the many evening and nighttime sequences contain a surprising amount of detail even in the deepest shadows, which is especially impressive considering that the film was shot on the cheap and digitally in the early days of the format. The uncompressed stereo soundtrack is well-balanced, with the lively street ambiance a near-constant but never overwhelming presence in the mix.

Extras

The 2005 audio commentary with Bahrani, director of photography Michael Simmonds, assistant director Nicholas Elliott, and actor Ahmad Razvi is quite informative about the various challenges that the crew faced throughout the low-budget shoot and the technical strategies used to create a specific look without expensive equipment. A new conversation between Bahrani, Elliott, and Razvi on the making of the film touches on some of these same topics, but also includes some fascinating insights on what it was like to work with an Iranian cast and crew so soon after 9/11. The discussion between Bahrani and his former professor at Columbia, scholar Hamid Dabashi, digs a little deeper into the director’s specific influences in Iranian literature and film, while critic Bilge Ebiri’s essay beautifully elucidates the overwhelming sense of stasis and entrapment the film locates in the lives of immigrants. The disc is rounded out with Bahrani’s 1998 short film, Backgammon, and a theatrical trailer.

Overall

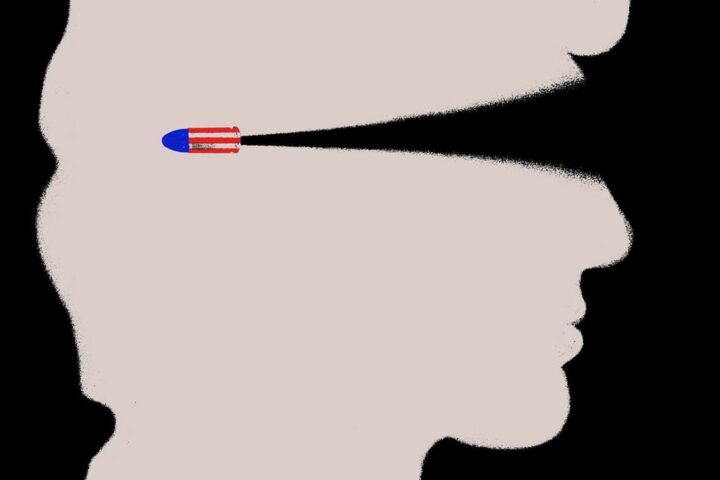

Criterion’s handsome new HD transfer of Ramin Bahrani’s feature debut is a testament to the film’s vital, unglamorous depiction of New York City in the wake of 9/11.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.