In the nearly two decades since the release of Davis Guggenheim’s An Inconvenient Truth, the “inconvenience” of climate change’s accelerating global impact has mattered less and less to leaders on the right, which is impossible not to see as a byproduct of the erosion of the idea of objective truth. Directors Jon Shenk and Bonni Cohen followed up Guggenheim’s film with a 2017 sequel that was more interested in glorifying Al Gore than in reigniting the public’s desire for an immediate, drastic response to the crisis. With their new film, The White House Effect, also co-directed by Pedro Kos, the filmmakers keep their focus on the issue at hand, lending the documentary a specificity and urgency in both its purpose and execution.

Using exclusively archival footage, The White House Effect transports viewers back to that period in American politics from the late 1970s through the early ’90s when the widely accepted consensus that climate change was an existential threat was systematically undermined. The film meticulously yet concisely probes how, why, and when our understanding of the greenhouse effect went from a scientific certainty to it being up for debate.

The White House Effect covers the impact of the U.S.’s 1979 energy crisis as well as the lasting effects of the deregulation policies of the Reagan administration. But the bulk of the film focuses on George H.W. Bush’s presidency, from 1989 to 1993, during which time the U.S. was on the brink of leading the world toward a massive reduction of carbon dioxide emissions, only to change course as the forces of global energy flexed their powerful muscles.

At 96 minutes, the documentary perhaps inevitably provides only a broad overview of all the competing forces at play. But it achieves a valuable focus through its fixation on Bush’s shifting loyalties between two members of his cabinet: his chief of staff, John Sununu, and his director of the Environmental Protection Agency, William K. Reilly. Through the archival footage of these two men, both in press conferences and in filmed interactions with Bush himself, we witness a battle between science and capital that was at its genesis and is still ongoing today.

It’s at once fascinating and unnerving to behold how fully convinced Bush was early on in his term that global warming had to be dealt with. And The White House Effect carefully documents how this belief and determination were held almost universally by people across party lines. If making Sununu the film’s big bad is a bit of an oversimplification, he’s certainly deserving of derision, as he’s not only smug in his manner, but he was brutally effective in sowing doubt in the mind of the president, and by extension the Republican Party and its constituents.

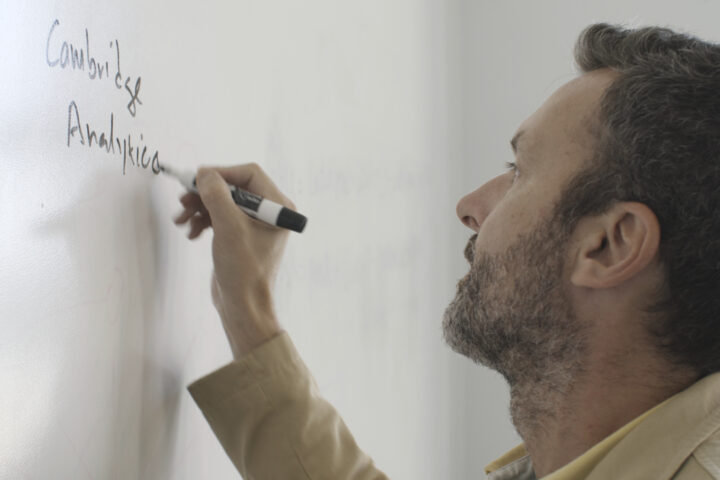

Through news reports, congressional hearings, and old interviews, the film exposes the concerted effort of the major oil companies, working hand-in-hand with Sununu, to undermine the scientific consensus on climate change with studies of questionable merit and scientists functioning as paid shills. As Sununu helps to sow the seeds of doubt in the minds of politicians and the public, we see the tides of power rapidly shift, not only in Reilly’s inability to enact any meaningful change within the U.S. and in global summits, but the media’s rapid reframing of the narrative. The White House Effect may not offer solutions to the global quagmire we find ourselves in because of these events, but in detailing how politics and climate science became intertwined, it may bring us one step closer to figuring out how to untangle them.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.