The opening shot of Souleymane’s Story finds Souleymane (Abou Sangare) standing in line in Paris for an asylum hearing, waiting to learn whether he officially counts as someone. He’s a recent arrival from Guinea, and across the film, director Boris Lojkine traces the man’s progress, at once literal and existential, through moments of hope and desperation.

After the title card, the film jumps back in time 48 hours to trace Souleymane’s daily grind as a delivery driver, during which time he’s at the mercy of ever-dinging notifications that remind him to enter codes and sometimes verify his face before schlepping food to customers. Turns out, Souleymane is renting an UberEats account from a friend, Emmanuel (Emmanuel Yovanie), who must occasionally verify Souleymane’s identity and collect his earnings. In the hands of the filmmakers, these petty humiliations accumulate into a quietly blistering indictment of a culture that’s conditioned immigrants to hustle, wait endlessly, and smile through it all, as if their sanity weren’t constantly under strain.

Souleymane’s Story employs the meticulous handheld cinematography popularized by the Dardennes. It’s a style that other films have imitated to lesser effect, but here it feels earned, echoing the fluid, restless motion of Souleymane’s life. When he’s knocked off his bike in a traffic accident and is banged up as a result, he doesn’t report it. Drawing excess attention to himself is a luxury he can’t afford. The camera, like Souleymane himself, simply keeps moving.

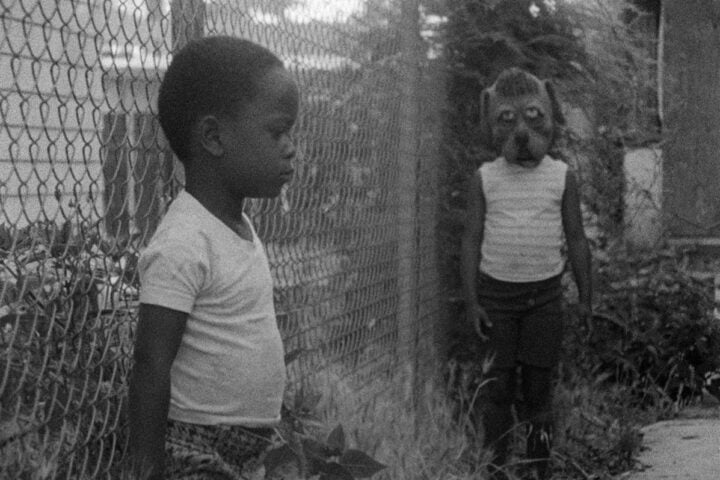

Souleymane’s Story announces its sharp metaphorical conceit when our protagonist pays a broker, Barry (Alpha Oumar Sow), to help him get his asylum papers. Barry crafts a politicized story for Souleymane to recite at his hearing with the OFPRA, France’s national agency responsible for processing asylum applications. By claiming political persecution at home, including being a member of the Union of Democratic Forces of Guinea, Souleymane will ostensibly improve his chances. Souleymane memorizes the script like scripture, all while recognizing the inhumanity of reshaping himself to meet someone else’s standards.

Lojkine and co-writer Delphine Agut largely avoid the trap of framing their protagonist solely as a vessel of suffering. They attempt—at times effectively, at others less so—to humanize Souleymane and the other immigrants in his midst by simply seeing them as more than victims. In a homeless shelter’s bathroom, the men banter and joke, reminders that they’re more than the sum of their traumas. Yet these moments are tinged with a paternalistic earnestness, as though the film doubts the audience will recognize the characters’ humanity without prompting.

Otherwise, the film is insightful whenever it keys itself to Souleymane hurtling through a series of unsettling encounters: from police stopping him mid-delivery, to Emmanuel assaulting him in a fit of rage, to his girlfriend, Kadiatou (Keita Dalo), accusing him of forgetting his roots. Each moment stings, but together they lay bare a larger truth: that modern life is engineered to grind certain people into paste while keeping others comfortably fed.

It all culminates in the asylum hearing. Souleymane, dressed in a collared shirt and trembling with exhaustion, begins reciting Barry’s script. But the interviewer (Nina Meurisse), having heard the same details in too many other hearings, presses him: “What’s your own story? It’s not too late.” And in this moment, Souleymane is confronted with the reality that a member of the OFPRA committee is uninterested in rehearsed narratives.

Souleymane’s Story powerfully depicts the immigration process in Paris as offering no clear path to success or acceptance. It’s a systemic uncertainty that creates ripple effects in the lives of individuals like Souleymane, which is reflected in the portrayal of a gig economy that exploits undocumented laborers. Rather than assign blame to any single individual, the film indicts an opaque system. In doing so, it avoids becoming a moral fable about good and bad characters and instead functions as a more nuanced and productive form of political commentary.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

“modern life is engineered to grind certain people into paste” strangely assigns no blame to any cause other than life itself. In reality, as immigrants know, it’s the far right’s domination of the Western political system, and the capitalist economies that most of us assume are just the natural state of things, that inflict so much suffering on the working class of any ethnic origin – and ‘class’ is a word the reviewer doesn’t dare mention.

The “far right” is not pro immigration you absolute dunce. The globalist system exists above even capitalism, and it is THAT system, that is exploiting native workers by importing cheap labour, then portraying them as victims.