Alec Guinness was a distinguished star of the stage when he transitioned to making films at the end of the 1940s, and though he made an instant impression in a pair of Charles Dickens adaptations (Great Expectations and Oliver Twist) directed by David Lean, his screen stardom truly soared with the dark comedies he made for Ealing Studios between 1949 and 1957, the four greatest of which have been assembled by Kino Lorber into a new collection.

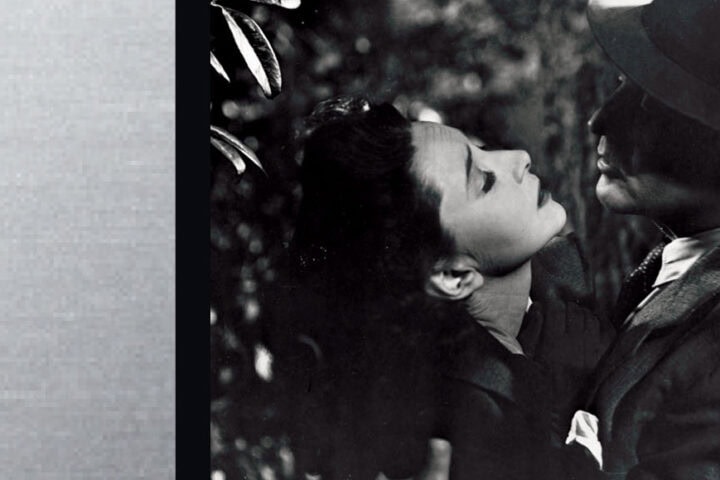

Guinness’s first (and greatest) work for the London-based studio, Robert Hamer’s merciless 1949 satire Kind Hearts and Coronets, definitively throws off the esprit de corps of the U.K.’s wartime cinema with a reassertion of brutal, aspirational individualism as Louis (Dennis Price), a stray branch on the noble D’Ascoyne family tree, systematically murders all the more legitimate heirs to the family’s name and fortune in order to advance himself socially. Guinness plays all eight D’Ascoynes that Louis murders, giving each their own eccentric touches while linking them all through a shared sense of idleness and total obliviousness.

The film, adapted by Hamer and John Dighton from Roy Horniman’s Israel Rank: The Autobiography of a Criminal, also makes expert use of its cluttered sets, the camera’s stodgy panning over various baroque decorations succinctly communicating the ossification of Britain’s upper class. And with its attention to subtle wordplay and the insinuations masked in one’s speech cadences, Kind Hearts and Coronets is one of the deftest pieces of comedy writing in film history, as fine a showcase of British cinema as anything by the Archers or Lean.

From 1951, Charles Crichton’s The Lavender Hill Mob sees Guinness playing a dull, fussy, ever-nervous bank clerk, Henry “Dutch” Holland, who exploits his position to instigate a gold bullion robbery. Holland rarely makes eye contact with anyone and walks with a shy hunch, all the better to arouse no suspicion when he pulls off his plan. Just as Kind Hearts and Coronets encourages its audience to root for Price’s killer over his stagnant victims, Crichton’s stellar heist caper presents Holland’s crime as a belated attempt at self-actualization by a man who’s lived his life to this point passively. And as things go increasingly wrong, it’s Holland’s visible effort to prevent his composed exterior from cracking that generates the film’s comedy.

Released only two months after The Lavender Hill Mob, Alexander Mackendrick’s The Man in the White Suit sends up the reactionary and progressive forces that inhibit scientific growth for the sake of maintaining the status quo. Guinness plays researcher Sidney Strattion, whose discovery of a durable textile fiber draws the ire of factory owners who fret the loss of profits that would ensue from long-lasting clothes, as well as that of unionized workers who know that any downturn in business would lead to layoffs and depreciated wages.

The film regularly appears on lists of the great British sci-fi movies, and it’s easy to see why. Besides the speculative fiction hook of Sidney’s chemical breakthrough, there’s a dystopian oppressiveness to the industrial areas and worker lodgings. Smokestacks loom over buildings that have bricks blackened by soot, and the spacious labs where Sidney does his work subtly emphasize a negative space that forebodes a future of depopulated work areas. It’s easy to look at the film’s satire as upholding both conservative and leftist notions of work and economics, but hidden just beneath the surface of Sidney’s potentially catastrophic innovation is the observation that true, life-benefitting progress is at fundamental odds with the needs of capital.

Guinness’s final Ealing movie would be 1957’s Barnacle Bill, a trifle that he only agreed to be in as a favor to director Charles Frend, but his last great work for the studio was 1955’s The Ladykillers, which reunited him with Mackendrick. Recalling the acidic comedy of Kind Hearts and Coronets, the film stars Guinness as the ringleader of a gang of bank robbers that poses as a classical string quintet to rent a flat near their next target. Guinness, sporting a garish set of fake teeth (shades of Lon Chany’s Phantom of the Opera), plays “Professor” Marcus with a permanent leer as he flatters and distracts the batty old Mrs. Wilberforce (Katie Johnson), whose gradual suspicions of her tenants forces them into increasingly desperate lies.

The Ladykillers has much to recommend it: Mackendrick’s excellent exploration of the cramped space of Mrs. Wilberforce’s buildings and how the robbers attempt to hide their work in it, as well as fine supporting performances from the likes of Johnson, Cecil Parker, and Peter Sellers. But the greatest joy remains the sight of Guinness’s self-style Marcus constantly adapting on the fly as the gang’s ruse unravels and the utter shamelessness of his continued protests of innocence even as the gang’s activities become more and more obvious.

Image/Sound

While the quality of the source prints varies, all four transfers look fantastic. The color photography of The Ladykillers reveals subtle shades in the film’s dominant pinks and greens that were previously absent on home video, while the monochrome cinematography of the other three films are all rendered with stable whites and blacks that look consistent even in the occasional fluctuations of available light in exterior location shots.

These films don’t always get the credit they deserve for their subtly rich visual grammar, and these transfers help pull some focus onto that aspect. During a Parisian chase in The Lavender Hill Mob, for example, vertiginous shots gazing up and down into the Eiffel Tower are now so sharp that the gleaming metal of the monument becomes an ominous, M.C. Escher-like recursive puzzle of overlapping beams and struts. The hollow, impersonal interiors of factories and labs in The Man in the White Suit become oppressively dull in their clashing shades of gray.

All four films come with their original mono tracks, and in each case dialogue is kept front and center while the occasionally antic music and chaotic sound effects of chase scenes pack an extra boost of volume without ever becoming distorted.

Extras

Each film comes with a commentary track by a film historian who knows their Ealing Studios history and contemporaneous postwar British cinema. A separate disc compiles the extras gathered on Kino’s earlier releases of the movies, including interviews with cinematographer Douglas Slocombe (who lensed every film here save The Ladykillers); T.E.B. Clarke and Charles Crichton, respectively the writer and director of The Lavender Hill Mob; and filmmakers who were inspired by the Ealing comedies, including Martin Scorsese, Stephen Frears, and the late Terence Davies. Rounding things out are theatrical trailers, an alternate ending of Kind Hearts and Coronets for its American release, and a restoration featurette for The Ladykillers.

Overall

Alec Guinness’s Ealing comedies remain high-water marks of British cinema, and Kino presents his four best films for the studio in glittering 4K transfers.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.