Nobody did more to perpetuate the gothic mode of storytelling on television in the 1960s and ’70s than Dan Curtis, the producer, director, and occasional writer who most famously created the daytime soap opera Dark Shadows in 1966. Over the five years of its initial run, quite a few of the storylines on Dark Shadows drew inspiration from classic tales of horror by writers like Mary Shelley, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Henry James.

Between 1968 and 1974, Curtis produced five innovative adaptations based on these stories, honoring the source material with titles like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula two decades before it became a bit of a fad for a film to include the author’s name in its title. One of the things that marks these telefilms as Dan Curtis productions is the continuity of certain cast and crew members, including actor John Karlen (who features in four of them), Trevor Williams’s impressively detailed production designs, and the always magnificent music of Robert Cobert, who served as composer for practically everything Dan Curtis did.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, from 1968, stars Jack Palance as the titular duo. Though clocking in at two hours, the film is a lean and muscular affair, with a surprising amount of bloody violence for late-’60s TV. Palance lucidly captures both the single-minded hubris of the good doctor and the arrogant swagger and sudden eruptions of ferocious cruelty of his alter ego. Despite the film’s limited budget, the production design yielded entire blocks of atmospherically fog-shrouded streets, lavish interiors of Jekyll’s stately home, and the grubbier laboratory where the transformations to Mr. Hyde occur.

Similarly, 1973’s Frankenstein opens with its arrogant lead subjected to the slings and arrows of calumny in a medical school lecture hall—because, as it says in the Book of Proverbs, pride goes before a fall. Like the novel, the film charts the destruction of Victor Frankenstein’s very existence at the hands of the creature he has endowed with life.

Robert Foxworth’s Victor is suitably commanding, if a bit one-note, while Bo Svenson as the creature gets a wider range of emotions to play, appearing at times wondrously childlike, piteously pathetic, and menacingly dangerous. Curtis and Sam Hall’s script is more deliberately paced than Jekyll and Hyde and more philosophically inclined, taking the time to examine the creature’s intellectual growth and responses to the outside world, which makes his ultimate turn to acts of murderous revenge all the more tragic.

The Picture of Dorian Gray, also from 1973, follows the 1945 film adaptation directed by Albert Lewin by giving artist Basil Hallward (Charles Aidman), the painter behind the titular portrait, a niece (played as a child by Kim Richards and as an adult by Linda Kelsey) to serve as an eventual love interest for the perpetually youthful Dorian (Shane Briant), who promptly falls under the libertine spell of Lord Henry Wotton (Nigel Davenport). But Curtis’s version hints more at Dorian’s fiendish pursuits, and by liberally quoting Oscar Wilde’s salacious dialogue, especially Lord Henry’s exquisite takedowns of conventional morality, it also has a wonderfully literary flavor that carries it along to its inevitably monstrous finale.

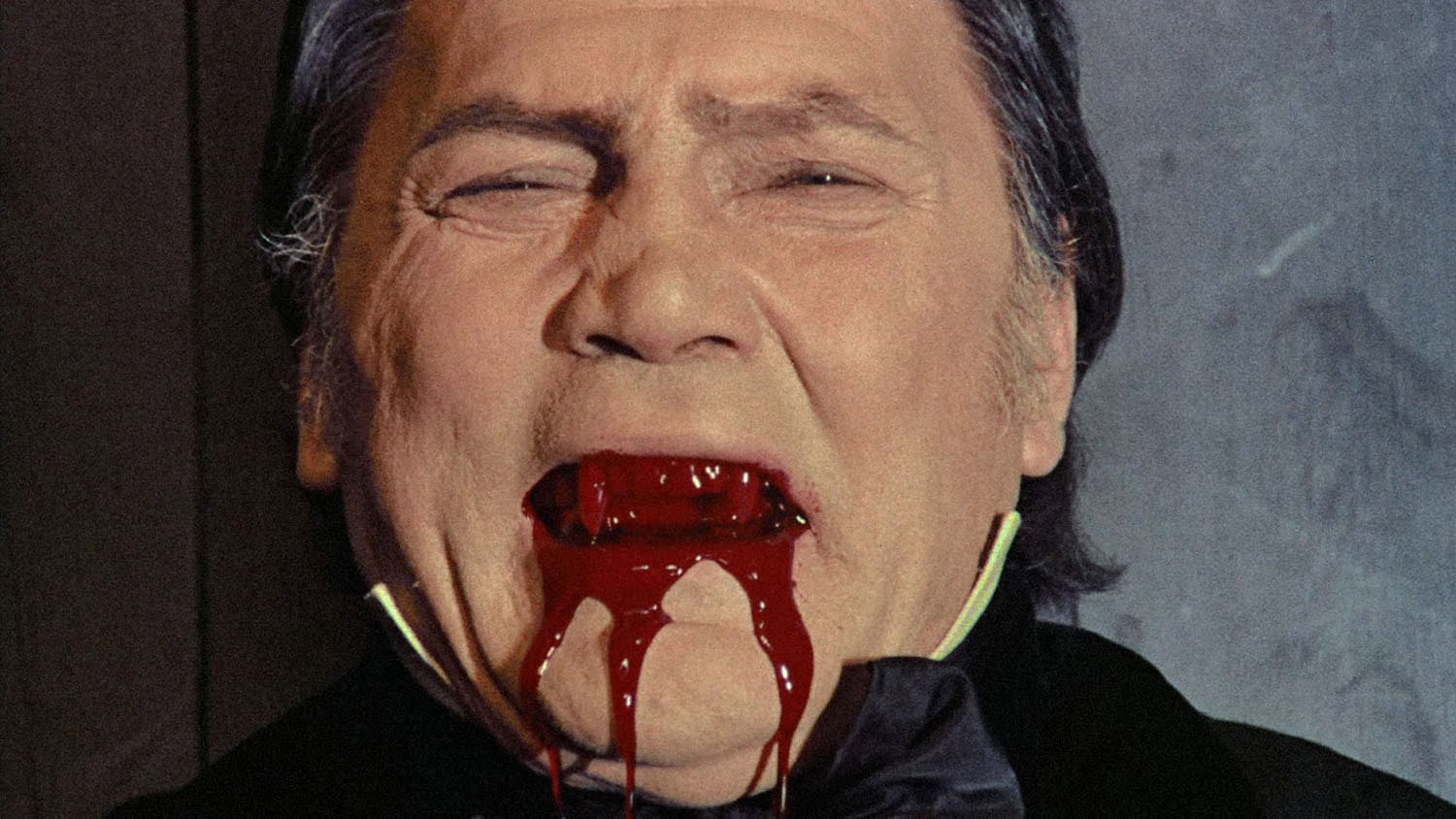

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, from 1974, stars Palance in the lead and Davenport as Van Helsing, and it instituted several significant changes that Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film of the same name would incorporate: It directly identifies Dracula with the historical Vlad the Impaler, and it has him discover the modern-day reincarnation of his long-dead love, though here that’s Lucy Westenra (Fiona Lewis) rather than Mina Murray (Penelope Horner). (Palance’s undead count comes across as more bestial than Bela Lugosi’s or Christopher Lee’s, as apt to reveal his overgrown canines in a snarl of frustration as in a sneer of haughty dismissal.) Filmed on location in England and Yugoslavia, this Dracula boasts some truly exceptional exteriors, and Trevor Williams outdoes himself with the sheer scale and detail of his interiors.

The Turn of the Screw, also from 1974, pays homage to The Innocents, Jack Clayton’s 1961 film version of Henry James’s novella, by also casting Megs Jenkins in the role of housekeeper Mrs. Grose. The script makes Miles (Jasper Jacob) an early teenager, older than in the book and earlier film, playing up the pubertal potency of his strangely sadomasochistic advances toward the governess (Lynn Redgrave). And like the source material, the telefilm strongly suggests that the ghostly visitations of Peter Quint (James Laurenson) and Miss Jessel (Katheryn Leigh Scott) are the product of the governess’s repressed sexuality, especially in a dream sequence where the supposedly loathsome Quint turns up in her boudoir only to meet with open arms.

In 1974, Curtis contributed four gothic tales in contemporary garb to ABC’s Wide World of Mystery series. Three of them, Shadow of Fear, The Invasion of Carol Enders, and Come Die with Me, use the venerable gothic conceit of the substantial inheritance and the murderous lengths to which the unscrupulous will go to inherit. The outlier is Nightmare at 43 Hillcrest, which is more of docudrama than a gothic melodrama. After mistakenly raiding the home of an innocent family looking for drug dealers, police officers plant heroin on the premises. Though justice is served thanks to an honest cop (John Karlen) and a sympathetic ADA (Mariette Hartley), the final crawl makes it clear that the Leyden family are nonetheless ruined.

Three years later came Dead of Night, a three-part anthology film written by horror icon Richard Matheson that, like Curtis’s earlier Trilogy of Terror, slowly builds up to its most memorably horrifying segment. “Second Chance,” adapted from a short story by Jack Finney, is the sort of genial, well-intentioned tale that would’ve been a fine fit for the Amazing Stories series of the ’80s. “No Such Thing as a Vampire,” in which a husband (Patrick Macnee) thinks his wife (Anjanette Comer) is cheating on him with his friend (Horst Buchholz) and uses a series of alleged vampiric attacks to gain his revenge, is darker, starker stuff. But best in show is the skin-crawling “Bobby,” the story of a bereaved mother (Joan Hackett) who works some black magic to bring back her drowned son (Lee H. Montgomery, who played the son in Curtis’s theatrical film Burnt Offerings), except Bobby isn’t quite the same loving son anymore.

Dan Curtis’ Classic Monsters, Dan Curtis’ Gothic Tales, Dan Curtis’ Late-Night Mysteries, and Dead of Night are now available on Blu-ray from Kino Cult.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

As always, a superbly written and usefully informative review by Budd Wilkins. Now I am confidently free to divert a bit of earthly treasure towards acquiring more Dan Curtis entertainment for my disc library.