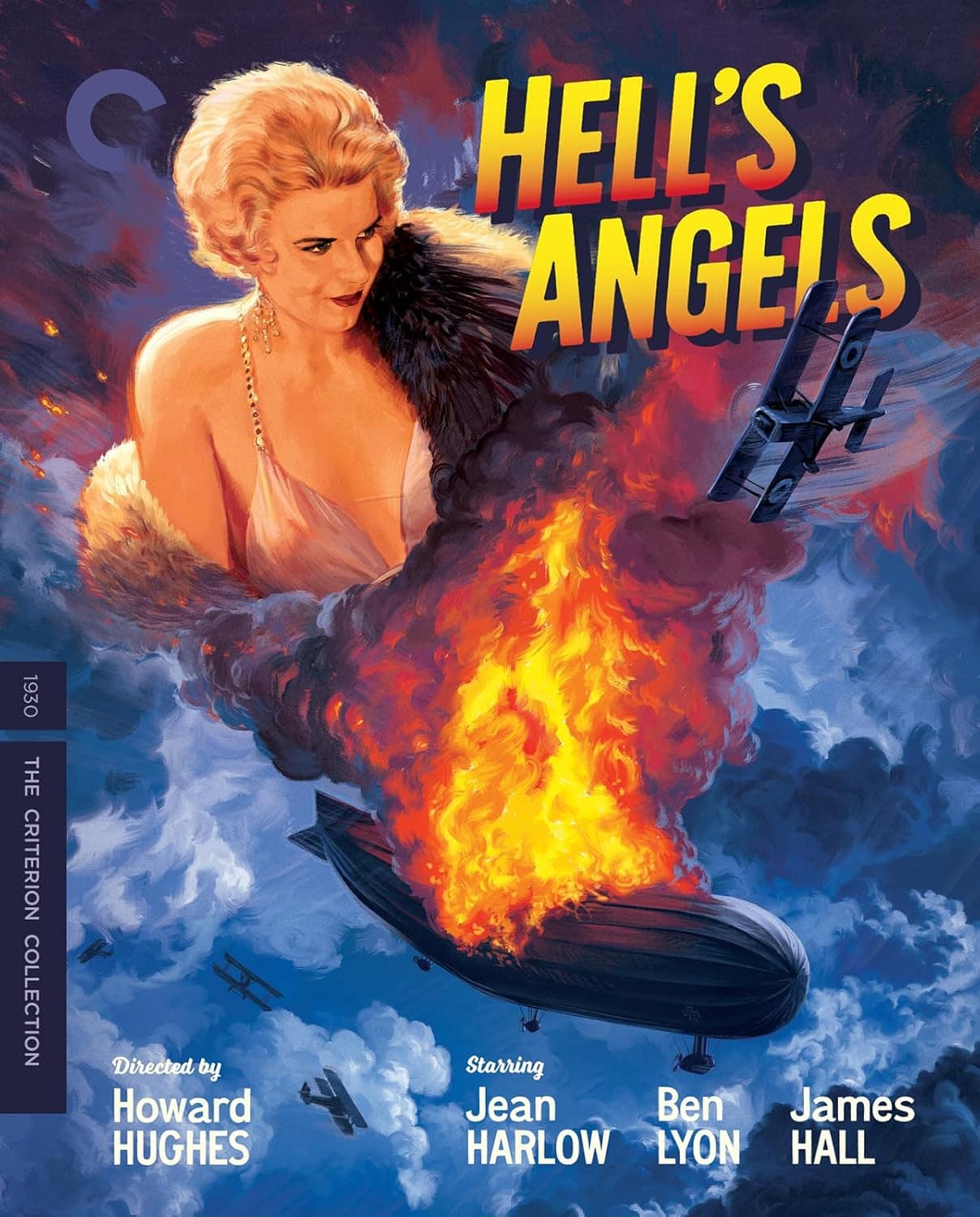

Howard Hughes’s Hell’s Angels is a fascinating oddity in Hollywood history. Repeatedly boondoggled by the business mogul and producer’s exacting demands until he took up directing duties, the production lasted so long that what began as a silent film had to be updated to a talkie to reflect the technological upheaval in Hollywood at the end of the 1920s. The final product is an unwieldy beast, a tonally inconsistent, haphazardly edited, occasionally spellbinding work of sheer bloody-mindedness.

Howard Hughes’s Hell’s Angels is a fascinating oddity in Hollywood history. Repeatedly boondoggled by the business mogul and producer’s exacting demands until he took up directing duties, the production lasted so long that what began as a silent film had to be updated to a talkie to reflect the technological upheaval in Hollywood at the end of the 1920s. The final product is an unwieldy beast, a tonally inconsistent, haphazardly edited, occasionally spellbinding work of sheer bloody-mindedness.

Opening on the eve of WWI in England, the film introduces nice-guy Roy (James Hall) and his rakish brother, Monte (Ben Lyon), along with their German friend Karl (John Darrow), anxiously referencing the growing geopolitical tensions between their respective countries. Karl, a foreign exchange student, even pledges not to take up arms against his second home. Soon, though, the three men find themselves swept up in the meat grinder of the Great War, each ending up in their respective homeland’s nascent air forces.

Hell’s Angels spares few thoughts for empty patriotism. We see Roy and Monte enlisting only because of social pressure from the women and elderly who will remain on the homefront. Driving the point home is a moment in which a pretty young woman is seen standing next to the enlistment board and offering kisses to any man who signs up.

Roy and Monte care far less about preparing for battle than they do finding women during their downtime, and both men end up embroiled with Helen (Jean Harlow), a socialite whose innocent looks bait the naïve Roy and whose underlying lechery appeals to Monte. Not unlike Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel, which came out the same year, Hell’s Angels hinges, at least at first, on the drama of corrupt and corruptible men meeting their match in a woman whose survivalist streak allows her to ruthlessly navigate a man’s world.

Eventually, though, the film’s first hour is revealed to be a preamble to the war scenes that clearly motivated Hughes to back the project in the first place. An aviation pioneer, Hughes put an extraordinary—and wildly dangerous—amount of effort into staging aerial combat scenes with real planes operating in tight choreography. To make things even more difficult for himself, the filmmaker also experimented with color processing, from an early sequence back on the homefront in two-strip color to battle scenes that update silent-era tinting techniques with fine-tuned emphasis on things like the flames erupting from the ignited hydrogen of a blimp.

Hell’s Angels may want for a unifying artistic vision, but it has its arrestingly evocative moments, like the scene where a German zeppelin commander orders his subordinates, including Karl, to jump overboard in order to give the airship the lift and speed it needs to escape capture by the British. Horrifically, most men obey, and on the soundtrack, only the low drone of the ship’s engines scores their otherwise silent leaps into the obscuring wisps of clouds. The eerie calm of the sequence recalls the poetic realism of early French masters like Jean Epstein and Jean Vigo, and in curtly summarizing the death-drive nationalism that drove World War I, Hughes inadvertently portends the mania that would eventually sweep through Germany.

It’s fitting that Hell’s Angels is mostly remembered as the launchpad for Harlow’s career. Her inexperience shows in her awkward line deliveries, but her screen presence is so magnetic that it’s no wonder she was the centerpiece of the film’s marketing. She embodies the undisciplined, at times amateurish, but always captivating nature of Hell’s Angels, which stands alone among early talkies for the epic sweep of its ambition and its fearless quest to find out just how far you can push the limits of filmmaking technology of the time, narrative coherence be damned.

Image/Sound

Criterion’s 4K transfer is one of the finest-looking presentations of a film this old. Even the images taken from airplanes are remarkably detailed, suffering some inevitable loss of definition from the limits of high-speed photography of the time but otherwise capturing the subtleties of shadows and light playing over plane fuselages and pilots’ faces in close-up. In more controlled lighting conditions, textures are stable, with the presentation showing a full range of whites, silvery grays, and deep blacks. The two-strip color scenes look immaculate, with the reds of Jean Harlow’s lipstick particularly popping against the earthier shades of green and brown.

For a film from the early sound era, Hell’s Angels’s soundtrack is inevitably tinny, and there’s also an expected start-stop abruptness to the sound effects. Still, the elements—dialogue, effects, and music—are nicely balanced, with the dialogue easy to discern, and with no major muffling.

Extras

Robert Legato, the visual effects supervisor on The Aviator, discusses the extensive research he did into the making of Howard Hughes’s film in order to recreate the behind-the-scenes shooting conditions of the aerial scenes for Martin Scorsese’s biopic. Legato marvels at the dangerousness of Hell’s Angels’s flying choreography, and notes that some pilots did in fact die during the making of the film—a grim testament to Hughes’s monomaniacal vision.

Elsewhere, critic Farran Smith Nehme provides an extended overview of Harlow’s brief but bright career, from her first major role in Hell’s Angels to her untimely death in 1937. The disc also comes with silent outtakes with explanatory commentary by Harlow biographer David Stenn. An accompanying booklet by journalist Fred Kaplan breaks down the gargantuan undertaking of the film’s production, as well as its technical breakthroughs.

Overall

Howard Hughes’s early talkie is an unwieldy, fascinating piece of film history, and Criterion’s 4K gives it the shimmering presentation that it deserves.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.