Most of us know that football players make enormous sacrifices to be successful, so the way that Justin Tipping’s Him posits a situation where those sacrifices take the form of a pagan ritual isn’t as far of a leap as it might seem. Set any random NFL game—all those bodies smashing into one another on the football field—to a score by Bobby Krlic and you’ll get something resembling a horror film. And that’s not even taking into account all of the behind-the-scenes problems with the sport as an American institution.

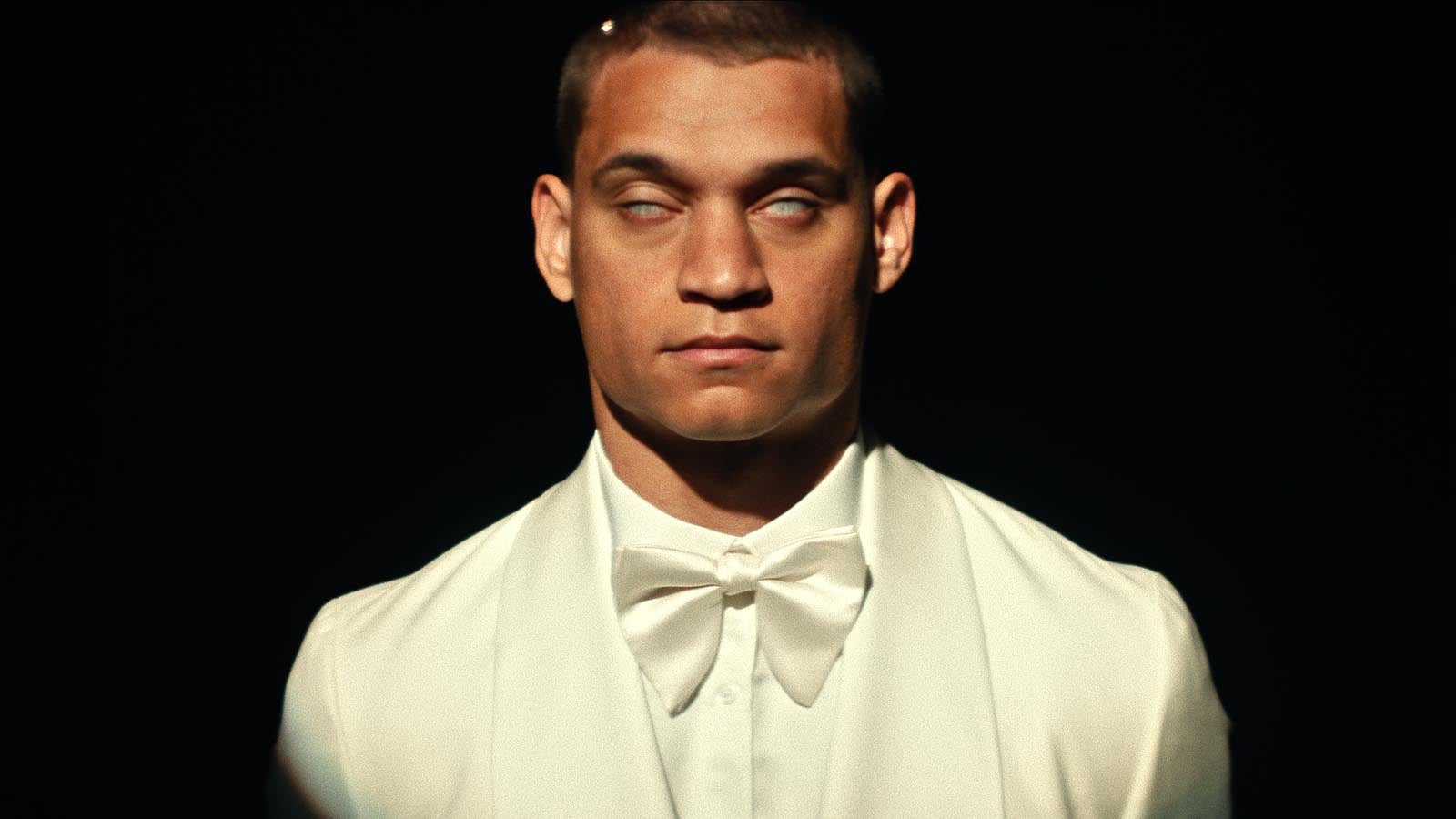

The correlation of football to an arcane tradition, though, is the only novel insight offered by Him. Still, and much like Tyriq Withers’s Cade Cameron, the absolute adonis of a potential draft pick at the center of the story, the film’s intoxicating aesthetics carry it a long way.

Him begins with Cade’s career being threatened when a random attack leaves him with the early symptoms of brain damage. From there, the film leans in on turning the world of football into a show of abstract horrors. Mascots, painted fans asking for autographs, team owners leering over draft picks like slave owners—all of it feels profane, and it rings uncomfortably true.

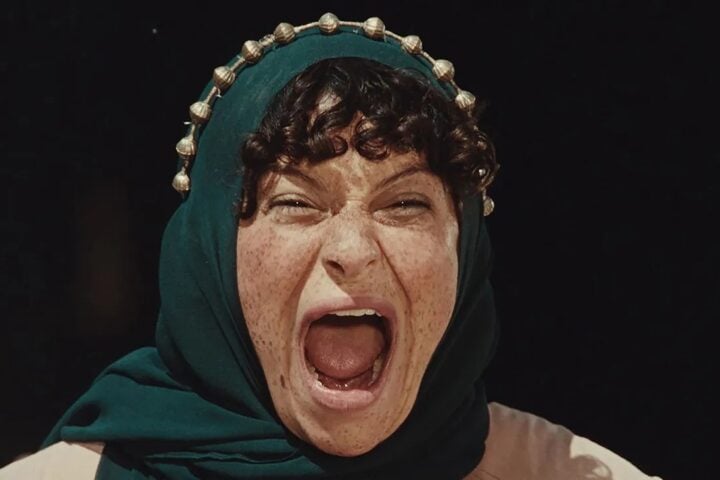

One day, San Antonio Saviors franchise player Isaiah White (Marlon Wayans), whose career is in its twilight, comes to the still-recovering Cade with a proposal: Train at Isaiah’s desert compound for a week, and if he’s still got the goods, Isaiah will push him for the team. Part Baptist preacher, part Terence Fletcher from Whiplash, part Colonel Kurtz from Apocalypse Now, all of it funneled through the single-minded, glory-focused hustle mindset, Isaiah is an unyielding force of nature, with Wayans’s performance holding the scattershot plotting of the film together through sheer will, and more than a few bloody grins.

But when Wayans isn’t on screen, the training sequences at Isaiah’s compound feel predictable—a violent trial by fire whose trajectory is an obvious excuse for football-themed horror. Watching all the blood, bashing, and hedonism that the film luridly trots out, you keep hoping for it all to be inextricably tied to the inconvenient realities of the sport.

There are glimpses of that here and there. Isaiah gives a brief, chilling history lesson in his very first scene about the lethal and racist origins of football, and Jim Jeffries’s nihilist team doctor, who becomes akin to Him’s deadpan Greek chorus, coldly warns Cade of the dangers and horrors of the sport, while continuing to pump him full of gallons of performance-enhancing drugs. But even when the film gets around, in its climax, to acknowledging how Black men’s bodies are obliterated at an altar built by wealthy white men, it all feels so clumsy, and the script is almost hesitant to connect that to everything else about Cade’s de-evolution.

Even with the low-hanging fruit of CTE so ripe for the picking, the most that Him does to incorporate it into the narrative is a brief bit of visual subterfuge where we get a Mortal Kombat-esque X-ray view of a cranial impact. There’s so much more to be said about the way football hollows men out. Which is to say, Him leaves you wishing that the aspirational way the sport is presented in real life—especially to marginalized communities—had been read for filth.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.