Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich’s The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire is less concerned with shedding light on its subject—the under-translated spouse of poet and Martiniquais politician Aimé Césaire—than with the quandaries involved in attempting to do so. Zita Hanrot, the actor tasked with portraying Suzanne Césaire, says as much: “We are making a film about an artist who didn’t want to be remembered.” Accordingly, this film essay grapples with the ethical and political considerations raised in the effort to retrieve Césaire from oblivion.

Fragmentary and self-reflexive, The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire could almost be mistaken for a behind-the-scenes documentary intended to supplement a more conventional film. As if preparing for their roles, the actors—Motell Gyn Foster plays Aimé Césaire and Josué Gutierrez plays André Breton—read and discuss snippets of Suzanne Césaire’s essays in lush surroundings. These writings were published between 1941 and 1945 in Tropiques, the journal that she ran with her husband. A few charged scenes hint at the possibility of a love triangle between the Césaires and Breton, who visited the couple in Martinique during WWII.

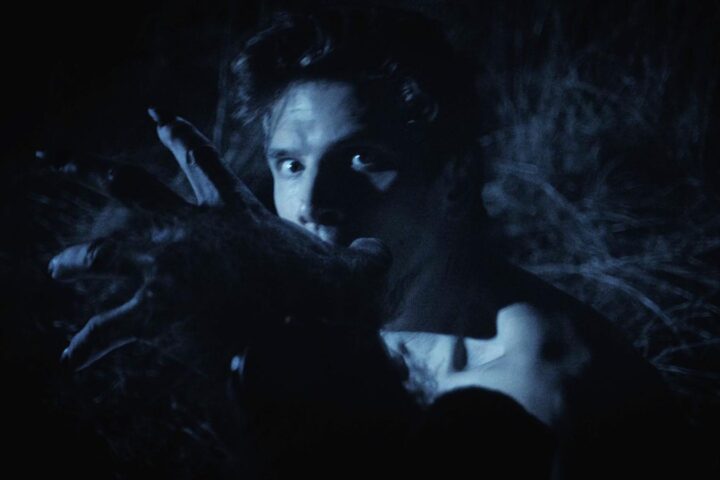

Preoccupied with its own right to exist, this film traffics in the aesthetics of negation, darkness, and opacity, an approach realized visually from the opening shots, so murkily lit that the figures they depict, dancing to polyrhythmic drumming, are all but reduced to silhouettes. Later on, Hanrot (speaking as herself) brings up the ambivalent role of nature in the poet’s work. Nature is so beautiful, according to Suzanne Césaire, that it “camouflages the colonial reality.”

It can be no accident, then, that a significant portion of the film’s 75-minute runtime is taken up with B-roll of tropical landscapes. Rather than attempt to depict what we’ve been told the camouflage conceals, The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire confronts us with the camouflage as such. And doubly so, as it turns out: Shot in Florida, Ehrlich’s film offers an ersatz “Martinique,” like the Spaghetti westerns of the ’60s and ’70s that were shot in Almería, Spain.

But the beauty of nature—or that which we project onto it—camouflages not only colonialism but other interlocking forms of oppression that were less theorized in the Césaires’ time. At least in part, the film attributes Suzanne Césaire’s relatively sparse, albeit influential, artistic and theoretical output to the infamous second shift. Combined with her duties as a teacher, the domestic labor involved in raising six children left little time for poetry.

Here the film’s argument begins to flounder. Its evasiveness is justified by asking us to take at face value that Césaire didn’t wish to be remembered, largely on the basis that she discarded much of her writing, an act Hanrot equates with abortion. But it seems equally plausible that she simply didn’t have enough time to write to the level of her own exacting standards.

The film puts into practice something in the vein of postcolonial theorist Éduard Glissant’s concept of opacity, which insists on respecting the ultimate unknowability of the oppressed. Yet this reluctance to imagine Césaire’s life runs counter the explicitly revolutionary surrealist project outlined in the essays she did publish and, presumably, wanted people to remember.

That seems like a strange way to honor the woman who wrote: “Far from rhymes, laments, sea breezes, parrots…we decree the death of doudou literature. And to hell with hibiscus, frangipani, and bougainvillea. Martinican poetry will be cannibal or it will not be.” Far from such polemical exuberance, and resigned to the impossibility of representing its subject in all her complexity, Ehrlich’s dour film argues unconvincingly against art’s right to imagination.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.